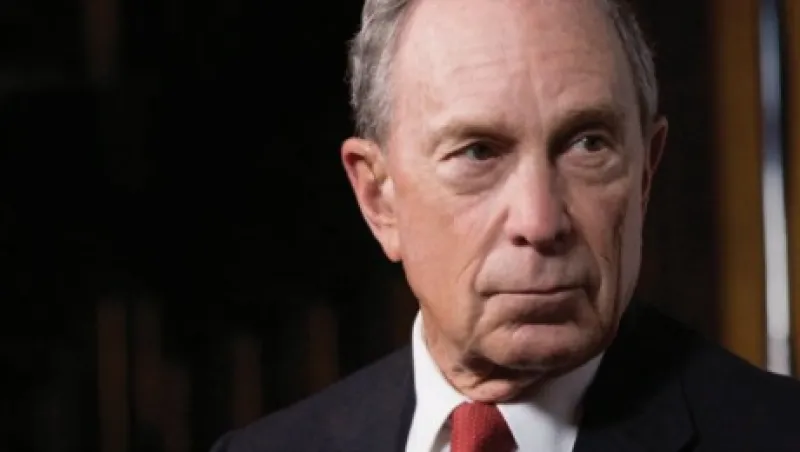

When former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg announced in March that he would not be running for U.S. president, at least one person may have been quietly cheering: Bank of England governor Mark Carney. In his role as chair of the Financial Stability Board, Carney had tapped the billionaire businessman in December to head up the FSB’s newly created Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures — a position Bloomberg would likely have had to relinquish given the rigors of a presidential campaign.

Bloomberg was a logical choice to chair the task force, which was first proposed by Carney during a speech at a Lloyd’s of London event last September. During his 12 years as mayor of New York, he spearheaded environmental initiatives like the NYC Clean Heat program that dramatically improved the city’s air quality. As Special Envoy for Cities and Climate Change to United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, Bloomberg in 2014 helped launch the Compact of Mayors, a global coalition of officials committed to reducing carbon emissions and making cities more resilient to climate change that has grown to more than 500 members. And Bloomberg Philanthropies — a nonprofit that distributed $510 million in 2015 — has been actively engaged with groups in China and India to tackle climate issues.

“Climate change is the biggest problem facing the world,” Bloomberg, 74, tells Institutional Investor. “If things spiral out of control and the planet starts getting hotter and hotter and there’s no stopping it, you literally will eradicate every single living thing. The planet would look like Mars.”

Carney announced Bloomberg’s appointment during the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris (COP21), citing the ex-mayor’s “unparalleled track record in a broad range of fields and his lifelong commitment to open and transparent financial markets.” For his part Bloomberg spent five days at COP21, speaking at several events, including a meeting on December 4 he co-hosted with Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo that attracted more than 440 mayors to City Hall for the Climate Summit for Local Leaders. “The cities have signed up to provide environmental data on their cities annually on a comparable basis,” Bloomberg says. “And why do the mayors want to do that? Because they think it’s a competitive advantage for their cities.”

The FSB, of course, has been charged by the Group of 20 nations with protecting the stability of the financial system, not saving the planet. But as Bloomberg explains, “everything has a financial component to it,” and the effects of climate change — extreme weather, coastal flooding, global warming — are having a real economic impact on companies, banks, insurers and investors. “The fascinating thing is that there are no businesspeople who stand up and say climate change doesn’t exist,” Bloomberg adds. “Why? Because you would get fired.”

In January the FSB revealed the membership of the 31-person task force, which includes vice chairs Denise Pavarina of Brazil’s Banco Bradesco, Graeme Pitkethly of Anglo-Dutch consumer products maker Unilever, Christian Thimann of French insurer AXA Group and Yeo Lian Sim of the Singapore Exchange. Its mission is to develop voluntary guidelines for companies across industries on what to disclose in financial reporting about “the physical, liability and transition risks associated with climate change.” The task force presented the first phase of its work — a 64-page report laying out the project’s goals and scope, as well as seven principles for effective disclosures — to the FSB on March 31. It will deliver the final, more detailed report with specific recommendations and disclosure guidelines before year’s end.

Members of the task force admit that the time frame is challenging. “It’s a crazy deadline,” says former Securities and Exchange Commission chair Mary Schapiro. “It’s very tight.”

“Mike [Bloomberg] and Carney would be disappointed if we weren’t somewhat ambitious,” adds Curtis Ravenel, global head of sustainable business and finance at Bloomberg LP. “We want to be ambitious but practical.”

Schapiro, now vice chair of the advisory board of consulting firm Promontory Financial Group in Washington, was brought in by Bloomberg as part of a secretariat that includes Ravenel and Promontory managing director Didem Nisanci, Schapiro’s chief of staff at the SEC. Schapiro has worked closely with Bloomberg and Ravenel on the board of SASB, a San Francisco–based nonprofit that is creating sustainability accounting standards for U.S. companies. Climate-related risks are among the material disclosures recommended by SASB. “One of the things we’re going to try to do is build off the many regimes that are already out there, including SASB,” Schapiro says.

One problem in tackling climate risk is that there are so many different voluntary guidelines and mandatory requirements for disclosing it — Carney identified “nearly 400 initiatives to provide such information” in his September 2015 speech at Lloyd’s of London. In its Phase 1 report, the global task force provides details on an alphabet soup of frameworks, including the CDP, CDSB, GRI, IIGCC, IIRC and SASB. A critical goal of the task force is to come up with consistent disclosure rules, says member Jane Ambachtsheer, chair of responsible investment at consulting firm Mercer. “There are lots of different market- or sector-specific reporting guidance and frameworks around climate risk,” she explains. “A key objective of the task force is to take a step back from that and try to focus on financially relevant climate disclosures, looking at all kinds of risk, both historical and forward-looking.”

The hope is that once companies start uniformly reporting about their climate-related financial risk, they will do something to reduce it, including decreasing carbon emissions. “If you get the information out there,” Bloomberg says, “in their own self-interest, the parties that are potentially impacted [by climate change] will take appropriate steps to try to solve it.”