Credit: GettyImages, Weiquan Lin

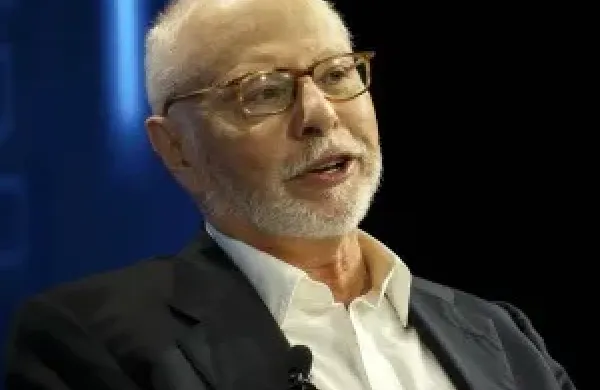

Being a dedicated data nerd has turned Philip Zecher into something of a rock star in the college endowment world.

When Zecher was named the first in-house chief investment officer at Michigan State University in 2016, he shook up the portfolio by taking a cold, hard look at the numbers and filtering out the noise. He strived to avoid the so-called endowment effect, the inertia and overconfidence that familiarity can bring, and ultimately crafted a more focused lineup of funds.

Zecher, a nuclear physicist PhD and a former risk manager for hedge funds who also studied behavioral economics, has had success. MSU’s endowment has grown under his watch from $2.4 billion to $4.4 billion, mostly as a result of investment gains.

“Phil’s a role model for what he’s done with that office,” says Stan Sokolowski, deputy CIO of fixed-income firm CIFC Asset Management, who serves with Zecher on the board of the Michigan State University Research Foundation.

Zecher understood from day one that people make bad choices out of habit and that change is hard.

“First impressions matter,” he says. “The first things you learn about something often are very hard to try to unlearn later. We also know that once you've been told a story about something that the story sticks.”

Zecher already had some experience trying to decide which investments to make, or keep, at MSU because of his previous role on a university committee overseeing the investment portfolio, which was then being run by an outside consultant. “Recommendations were being made for this manager or that manager, and there were lots of assumptions being put out there about how they make money, when do they do well, when they do not do well.”

But, he says, “the scientist in me was very much like, ‘Well, OK, can I prove that, or at least can I demonstrate that?’ I would often go back and try to find data to validate or demonstrate whatever the claim was. And it often was not satisfying.”

In his new role, Zecher was determined to evaluate funds while trying to ditch as many biases as he could. A big one was the endowment effect – a broad psychological concept that applies to a broad range of behavior, including investing.

The principle is simple: “There's a product out there that you wouldn't go out right now and put your money down to buy. But if you own that same product, you are not likely to sell it,” he said in an interview covering everything from the new approaches he brings to managing an endowment to rocket launches and his initial skepticism about investing in private markets.

The same applies to funds in a portfolio. “If you are already invested in the fund, you’re likely to not want to sell it even though you wouldn't buy it,” he says. Ownership itself “endows” a product with value. “That makes no sense.”

So Zecher turned to a blind test of sorts, stripping the names from a list of the holdings in MSU’s public equities portfolio — both long-only and hedge funds — to look at their performance numbers, Sharpe ratios, Sortinos, and other metrics. He then put together a page full of statistics for each fund, without disclosing whether it was passive or active. Finally, the investment team had to “vote it off the island or keep it on the island.”

It was hard to part with some of the funds, he says, but by 2018 Zecher had shrunk the number of hedge funds in MSU’s endowment portfolio from 50 almost in half. Even so, he has kept the allocation to hedge funds in the portfolio steady at a little over 20 percent. That includes big names like D.E. Shaw’s Oculus Fund, Elliott International, Two Sigma AR Enhanced and Viking Global. MSU also has investments in GMO, DSM (a BNY Mellon municipal bond fund) and the BNY Stock Index.

Based on annualized returns over 10 years, MSU ranks in the top 10 of university endowments.

Scott Eston, who served with Zecher on the MSU Research Foundation as well as the subcommittee that previously oversaw the endowment’s investments, recalls the decision to name Zecher as CIO. At that time, Michigan State was one of the biggest endowments still essentially managed by outside parties, in its case by a consultant.

“We thought that performance could be better,” he says. With Zecher on board, Eston says, “performance improved pretty quickly, and now it's been really good.”

Both Sokolowski and Eston say Zecher has managed the portfolio like the nuclear physicist he is. “I think just his natural curiosity and analytical skills all come together” in managing money, Eston says.

“Phil didn’t show up saying, ‘Oh I know this person. I know that person. I've got very strong beliefs about how this person manages money compared to that person,’” he says. “It's all about the analytics and whether or not the process and the results kind of hang together.”

As a member of the investment committee, Eston has watched Zecher in action. “He likes getting into these puzzles of trying to figure out what's real versus what's not reliable.”

Instead of relying on fund ratings from consultants or others, Zecher directly collects various quantitative measures around risk and return and has built his own daily index for the managers he uses.

Eston says Zecher would show them the indices without the names of managers, and ask, “‘So which one do you think this is?’ And of course we end up having our subconscious biases” and choosing the wrong ones. Even institutional investment professionals “end up kind of falling in love” with a fund that has had a recent string of good performance. He said that Zecher’s proprietary analysis would clearly illustrate how performance was sometimes less reliable as a measure of future success than other indicators.

The exercises helped the trustees feel confident about bringing the investment management in-house, says Eston.

Growing up in Lebanon, Ohio, Zecher knew by the age of six that he wanted to become a scientist. It was the height of the space era, and after visiting the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History he became enamored with astronomy. “My favorite place was the planetarium. And that was when the Voyager spacecraft passed Jupiter, and we had the first pictures back,” he recalls. Zecher soon had the privilege of hearing astronaut Neil Armstrong, an Ohio native who was the first person to walk on the moon, speak at the museum. (Later he was introduced to Armstrong by a friend of his father’s.)

But it was opening a physics book in seventh grade that got Zecher hooked on that fundamental scientific discipline. “I found my uncle's high school physics book, read it and drove my seventh-grade science teacher crazy asking questions from it,” he says.

Zecher was the first kid in the neighborhood who knew how to program computers. He had begun teaching himself how to program on a friend’s father’s Radio Shack computer even before the IBM PC debuted, which happened when he was in high school. By then, he says, “I was actually consulting around town. If businesses had a computer and it wasn't working, I was the one who got the telephone call if they couldn't figure it out. And I remember charging $20 an hour.”

Zecher became the first in his family to attend college and received his B.S. in physics from Ohio University. After graduating from OU in an honors program in 1990, Zecher says he was “burned out” and decided to take a job offer with Fidelity Investments — which he had never heard of — in its Cincinnati call center.

The job “sounded more fun than being stuck in a room all day with no windows and doing assembly-level programming on a computer,” he says. Within a few months, Zecher was transferred to Fidelity’s Boston office to rewrite the software that produced the daily reports that went straight to the CEO. But the lure of science brought him back to academia. He chose MSU to study for a PhD in nuclear physics in its graduate program, which has a flagship lab for the National Science Foundation and produces about 10 percent of all nuclear physicists in the U.S.

At the time, Zecher figured he would stay in academia. But he changed his mind because he wanted to live in New York City.

Zecher no longer lives in New York, but he remains in the tristate area — after persuading MSU to let him run the endowment office from Stamford, Connecticut. He also is the chair of the Connecticut Advisory Council, which oversees the state pension plans. (Living on the East Coast also gives Zecher the opportunity to engage in his passion for sailboat racing on the Long Island Sound. According to friends, Zecher takes a disciplined approach to that endeavor as well, competing in several regattas.)

In 1999, he co-founded Investor Analytics, a New York City-based risk advisory firm that attracted a French bank as its first client. But he ended up selling his services to the hedge fund and fund-of-funds industry. The firm was founded during the dot-com bubble, when seemingly fanciful ideas about the internet abounded. “Some people had this crazy idea that in the future you wouldn't even buy a CD for your software, you would just go online,” he quips. Investor Analytics was among the first to deliver data through the Web. He eventually sold the business and joined currency hedge fund EQA Partners as partner and chief risk officer, where he worked before starting MSU’s investment office.

Those prior roles inform how he operates the investment portfolio.

Although Zecher had served on an advisory committee overlooking MSU’s endowment for six years before becoming its CIO, he points out that he had never been an allocator before taking the job. “I look at it much more like a risk-management problem than an investment problem,” he says.

Zecher has made other changes to the way the portfolio is run. For example, he has stepped away from the standard type of strategic asset allocation model that he believes is an attempt to manage risk through what he calls an “ill-defined set of diversifications.”

To that end, MSU is focused more on global stocks. “To me, it's more a matter of not paying so much attention to where the company's domiciled because today every company practically uses one of three things. Either they use global labor, they use global supply chains or they sell globally,” says Zecher. And the economy is still global, despite the current tariffs being imposed by President Trump.

Plus, he says, investors err if they analyze companies in other countries the same way as they do those in the U.S. “If your model is based simply on taking a valuation model that works in the United States with our culture, and you apply that to anybody else and you don't take into consideration things like their culture, it’s not a surprise that it doesn’t work.”

Zecher notes that European companies are highly focused on the environment, thinking in terms of stakeholders as much as shareholders. “They are willing to forego profits that would raise the stock price if it benefits the environment,” he says. That is a very different attitude from what prevails in the U.S. “I'm not trying to make a value judgment as to which way is really better in the long run, just acknowledging that it is different,” Zecher adds.

He points to a chart with bubbles depicting the value of U.S. companies “created from scratch” over the past 50 years, compared with one for Europe, whose bubble is tiny in comparison. “When you look at this, it’s pretty clear the EU market and the U.S. market are not the same thing in the way they work and behave. So if your strategic asset allocation model says you should have X in Europe, my argument is basically that you’re simply picking it because of where it's at, and you’re ignoring the fact that these are very different marketplaces.”

Ray Gustin, the managing director of Drake Capital Advisors, a fund of funds that runs a managed account as part of the MSU portfolio, says that while many CIOs try to find out what others are doing, Zecher “definitely does not look to follow the herd.” Gustin says Zecher “loves strategies within the hedge fund world that are pure alpha strategies because he knows he can get beta or market directional exposure through his equity allocation.”

As Zecher sees it, an endowment fund is like a “perpetual 65-year-old” who wants 80 percent of the portfolio to be “full beta” but needs to make above market returns on the other 20 percent. “Back in the day, right, when you had 40 percent in bonds, you were investing in bonds that only paid maybe 7 percent. You take that return, that lower return, because you want to reduce the volatility.”

Risk-adjusted returns are fine for evaluation purposes, he says, but he recalls that the university president once told him that MSU “can’t spend risk-adjusted dollars.” It can only spend real dollars. And if the cost of money is near zero and the return is only 5 percent, “that’s not making enough for us to be able to feed the university what's necessary,” Zecher explains.

“We're a perpetual fund,” he says. “However, we need to live off the income of this at the same time. So for us to be completely in equities doesn't make sense because if there's a big market drawdown for a couple of years, then that means we’re not going to be able to fund the things on campus that we need to fund.”

To be sure, the trustees want to see great returns, he says, “but stability is actually the important part. Year after year, students get a scholarship. They expect that scholarship for four years. Faculty chairs, departments hire people based on some sense of what they're going to get out of their endowment. So that way we are not fully risked-up in equities.”

Gustin calls Zecher “a very disciplined thinker who is able to quantify his approach.” Even when markets are choppy, he says, Zecher keeps his cool. “He understands the long-term mandate of investing. He's very, very thoughtful.”

Private equity is a case in point. Like most endowments, MSU has turned to PE for what it hopes will be above market returns as well as stability. Initially he was uncertain about the asset class. (For one thing, those less-liquid investments can’t be analyzed in the scientific way he looks at his publicly traded equities portfolio.)

“When I started this, I was skeptical of private equity in general,” Zecher says. “I saw all the money that was going into it.” Still, it has performed well and become a huge chunk of the portfolio — 33 percent as of fiscal 2023, the most recent figures available. Some of the firms whose private equity funds are in the portfolio are Axiom, Centerbridge Capital, Cerberus, Fortress, Lightspeed and Thoma Bravo. (MSU also has invested in private real assets and private real estate funds.)

Of course, the past few years have been rocky. A year and a half to two years ago, he says, the market froze. “Distributions completely disappeared.”

“Before that, we were actually getting enough distributions to fund all of the new ones; we were out of the J curve in the private equity fund.” In 2021, a year of great VC returns, MSU’s venture capital book more than doubled in value — “if you believe the marks,” he adds.

Then everything stopped. “There was nothing to buy. No one was selling anything. The private equity portfolio went to maybe 10 or 20 percent of what it was during that time period.” The saving grace, he notes, is that there were also almost no calls for capital at that time.

Since then private equity funds have marked down their portfolios slowly, while the public market turned up. “So now relative to public, they [privates] look very undervalued. They've very much underperformed.”

Last fall, he says, distributions also started coming back. “It's not great, but we are seeing life come back into the system.”

After this disruption, Zecher says he stepped back and took a long-term view of private equity. “It shot up like crazy and it crashed, but it's on a longer trajectory. What we're really concerned about is at the end of the day, what did we make back from these funds? Did they actually add value?” By looking at the public market equivalents, he predicts that “private equity funds over time will earn better than the public equity market.”

The jury is still out on that, even in Zecher’s mind. As something of a rejoinder to his optimism, he likes to quote behavioral economist Amos Tversky, who died before his partner received the Nobel Prize in 2002 for the work the two did. Channeling Tversky, Zecher reminds us: “Once we've adopted a particular hypothesis, we grossly exaggerate the likelihood of that hypothesis.”