Ben Meng

(Illustration by II)

On Sunday, August 2, financial blogger Susan Webber — pen name Yves Smith — pressed “publish” on the post that would ultimately topple the chief investment officer of the largest public pension plan in the United States.

In the scathing missive, posted on her Naked Capitalism blog, Webber accused (Yu) Ben Meng, CIO of the $410 billion California Public Employees’ Retirement System, of making false statements on the personal financial disclosure forms that California public officials are required to fill out. What’s more, the post asserted that these documents show that Meng had conflicts of interest, holding personal investments in three of the same private equity firms in which CalPERS is invested.

Two days later, at 1:35 p.m. on August 4, an anonymous complaint landed in the inbox of the enforcement division of California’s Fair Political Practices Commission, accusing Meng of three separate disclosure violations.

From there, Meng’s defenestration was swift — and shocking. A terse press release appeared in reporters’ inboxes at 10:08 p.m. Pacific time the next night, announcing Meng’s resignation, effective immediately, with Meng claiming he was stepping away to “focus on my health and on my family.”

But behind the scenes the events leading up to his departure had been brewing for several months — and their abrupt, highly public conclusion capped the brief and tumultuous run of a CIO who had been a lightning rod for controversy during his tenure.

It was actually in April that the disclosure issues first came to light internally at CalPERS, when a compliance team flagged a violation: a $70,000 investment in shares of Blackstone Group, which Meng owned at the same time the pension fund made new investments in the firm, according to a Bloomberg report. A former colleague of Meng’s tells Institutional Investor that the then-CIO told this person at the time that an internal investigation had been done and that the issue was resolved.

Once the anonymous complaint was filed with the FPPC, however, it was only a matter of time before it entered the public sphere. Privately, CalPERS CEO Marcie Frost told Meng she planned to discipline him, though she considered the violation an oversight, according to Bloomberg. But she warned him to expect a furious backlash when the news eventually got out.

With the publication of the blog post on August 2, that’s exactly what Meng got. The soon-to-follow press release announcing his resignation sparked speculation that the decision wasn’t voluntary.

CalPERS denies that Meng was pushed out. “CalPERS has known about questions regarding Ben’s Fair Political Practices disclosure filings. These are private personnel matters and already have been addressed according to our internal compliance protocols,” board president Henry Jones said in a statement emailed to Institutional Investor. “CalPERS is moving forward and recruiting a new chief investment officer. A board meeting has been scheduled for August 17 to discuss personnel matters.”

But that’s too far in the future for California State Controller Betty Yee, who sent a letter to Jones on August 10 saying she found it “objectionable” that the board didn’t plan to discuss the issue until then.

“I am deeply disappointed in the actions of former Chief Investment Officer (CIO) Ben Meng and what appears to be a blatant disregard of conflict-of-interest laws and policies,” she wrote. “I believe the Board has an obligation to CalPERS members to determine whether Mr. Meng’s carelessness violated any laws or caused financial and reputational damage to the pension system. While the CIO’s resignation was appropriate, the Board’s obligation to CalPERS members does not end there. Rather, it calls for a swift and thorough inquiry into this matter and potential actions needed.” (Meng could not be reached for comment for this story.)

Yee urged Jones to call a special meeting of the board within 48 hours of receiving her letter; Jones denied the request and said the meeting will take place on the 17th, as scheduled.

Yee is not the only one who found the matter disturbing.

“The [disclosure issue] is really problematic,” says former CalPERS board member and investment employee JJ Jelincic, himself no stranger to controversy. (He was censured by the CalPERS board in 2011 after having been reprimanded for sexual harassment when he worked in its investment office; Jelincic said at the time that the accusations were politically motivated.) “I know Ben, I like him, I think he’s a smart guy; I don’t think there was any real intent to deceive. It was much more a carelessness and a sloppiness. However, if you’re the chief investment officer, you don’t get to be sloppy.”

The former colleague of Meng’s sees it differently, insisting that it’s a stretch to call Meng’s personal investments in the private equity firms a conflict of interest, partly because CalPERS was already invested in those firms before Meng arrived.

“I can absolutely understand where someone could legitimately say you don’t have to sell those things,” this person says. “CalPERS owns about 60 basis points of almost every publicly traded stock in the world. So if you own an index fund in your personal portfolio, someone could come forward and say, ‘You own IBM or Apple’ — is that a conflict of interest?”

The ex-colleague concedes that it may have been a lapse in judgment for Meng to continue holding on to the shares, but it didn’t amount to a deliberate attempt to enrich himself.

“I know Ben well enough to know that if that’s the case, it’s an inadvertent thing; he didn’t even think of it as being a conflict of interest in bad faith,” the person says. “That had nothing to do with any of the decision making whether to allocate those [private equity] funds or not. That’s pure, toxic bullshit.”

Ultimately, it didn’t matter whether or not a true conflict existed. The damage was done — and Meng seemed to realize that there would be no redemption.

Until recently, much of the criticism focused on Meng’s investment decisions — namely a plan to reach CalPERS’ ambitious 7 percent investment target by plowing more money into private equity and private debt investments, and borrowing against the pension’s assets to do so, a plan critics said was far too risky.

But that’s not all. Earlier this year, Meng also made what looked, on its face, like a massive investment blunder: He pulled CalPERS out of a tail-hedging strategy, designed to protect against equity market losses in the event of a downturn, in January — just weeks before the market tanked in March. The move cost the pension fund $1 billion, though one of the program’s designers says it was likely more.

The bad press began to pile up just in time for CalPERS to report underwhelming annual results. In June the pension reported preliminary returns of 4.7 percent — beating its benchmark of 4.3 percent, but less than stellar given that CalPERS remains just 70 percent funded.

For Meng the metastasizing controversies, coupled with the intense pressure and scrutiny that come with the nation’s most high-profile public investing gig, were too much, marking the end of nearly eight total years at the pension.

The stint as CalPERS CIO wasn’t Meng’s first role at the fund. Born in China in 1970, Meng first arrived in the U.S. “with a backpack and $200,” according to a Bloomberg interview, before earning advanced degrees from the University of California and ultimately becoming a U.S. citizen. He worked in several roles on Wall Street — as a senior portfolio manager at Barclays, a risk officer at Lehman Brothers Holdings, and a fixed-income trader at Morgan Stanley. Meng first joined CalPERS in 2008, working there for seven years as an investment director before leaving for Beijing to join China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange as deputy CIO, a job he held for three years.

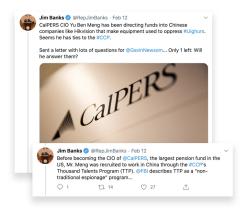

It was that role that landed Meng in the crosshairs of Congressman Jim Banks, a Republican representing Indiana. On February 12 the congressman posted tweets saying he had “lots of questions” about Meng’s connections to China and CalPERS’ investments in the country. Specifically, Banks accused Meng of “directing funds into Chinese companies like Hikvision that make equipment used to oppress #Uighurs,” referring to the ethnic minority group that the Chinese government has been accused of cracking down on. “Seems like he has ties to the #CCP,” or Chinese Communist Party, the tweet continued.

Read another tweet: “Before becoming the CIO of @CalPERS, the largest pension fund in the US, Mr. Meng was recruited to work in China through the #CCP’s Thousand Talents Program (TTP). @FBI describes TTP as a ‘non-traditional espionage program’ . . . .” He didn’t stop there, sending a letter to California governor Gavin Newsom urging him to fire Meng.

Meng also drew criticism from the Falun Gong, of all places, a spiritual group persecuted by the Chinese government. The Falun Gong–backed Epoch Times published an attack on Meng, criticizing what it called his “deep ties” to China’s government.

Banks’ accusations struck some observers as having an undercurrent of xenophobia, and CalPERS chief executive Marcie Frost fired back, calling the tweets “a reprehensible attack on a U.S. citizen” and throwing CalPERS’ support behind Meng, “who came to CalPERS with a stellar international reputation,” she wrote.

But the attacks deeply distressed Meng.

“That letter from the Indiana congressman — that really did bother him a lot,” according to the former colleague of Meng’s. “He didn’t say, ‘I’m thinking about leaving,’ but it surprised him and it bothered him. You feel like you’re doing a public service — after being CIO at SAFE, he could have gone to Goldman and made $5 million a year. He knew [CalPERS] and had his heart in the right place. It’s certainly possible that he started to think about leaving at that point.”

When asked to respond to allegations that his criticism of Meng smacked of xenophobia, a press secretary for Banks did not specifically address the charges, but referred II to a statement Banks issued following Meng’s resignation: “Taxpayers shouldn’t be forced to fund our adversary’s military,” it read. “With Yu Ben Meng’s departure, CalPERS now has the opportunity to correct its course and divest from companies within China’s military-industrial complex.”

The stress took a toll on Meng, who told the Financial Times on Tuesday that his health “has been deteriorating for six months.”

California’s Fair Political Practices Commission requires public officials to annually file the so-called Form 700, which is supposed to disclose their personal financial holdings and reveal any potential conflicts of interest. On April 1, Meng had just filed his second such form since taking the CIO job.

Filers must list any stocks they held in the previous calendar year that are worth more than $2,000. Any position that is sold during the course of the year requires disclosure of the date of the sale — and likewise with any purchases made over the same period, “to ensure that officials are making decisions in the best interest of the public and not enhancing their personal finances,” according to the FPPC’s website. The FPPC is reviewing the anonymous complaint against Meng to determine whether it merits an investigation, a spokesman for the organization tells II. Violations can result in fines of up to $5,000 each.

The August 2 Naked Capitalism blog post pointed to discrepancies between the forms Meng filed on April 1 and the one he filed the previous year. They show that Meng disclosed 46 positions in his January 2019 filing but listed just 22 stock positions in the April 2020 filing — and failed to disclose any sales in the latter filing, save for one. The blog also pointed out that Meng referred to the same positions using two different names on the two forms, making it difficult to compare them.

“The forms are not that difficult — but you could see how you could make mistakes on them without trying to be duplicitous or deceitful because the instructions were confusing,” says the former colleague of Meng’s.

What’s more concerning to outsiders is that the documents show that Meng personally owned the publicly traded shares of three private asset managers: Ares, Blackstone, and Carlyle Group, according to the forms. Since Meng took the CIO job, CalPERS had made new investments in funds operated by Blackstone ($1 billion) and Carlyle ($328 million), according to fund documents. Though not required to disclose the exact dollar amount of the holdings, Meng indicated that he owned between $10,000 and $100,000 worth of each of the companies’ shares.

Adds the former Meng colleague, “It makes it tough to do any public service if any personal investment you have, someone’s going to find a way to twist it into conflict of interest. That’s the challenge of working at CalPERS, because they own a little bit of everything.”

But another controversy was about to boil over. On April 10 — just a few days after Meng filed his Form 700 — II and other publications revealed CalPERS’ untimely tail-hedge unwind.

The tail-hedge program had been instituted in 2016, under previous CIO Ted Eliopolous, as a means of protecting the pension from the kinds of drastic equity losses it had experienced in the global financial crisis of 2008. Tail-risk hedging programs consist of sophisticated derivatives strategies, but the way they are meant to work in practice is fairly simple: As with an insurance policy, the owners of tail-risk hedges pay small premiums for portfolio protection, making the investment a slight money loser in periods of rising equity markets. But these programs are designed to earn big payouts if the event they are insuring against — namely, a big equity market drawdown — occurs. CalPERS’ investment in the strategy was managed by two outside firms, Universa Investments and LongTail Alpha, and cost the plan about 5 basis points (0.05 percent of its total assets) to run during the plan’s fiscal year ending in June 2019.

CalPERS made the decision in October 2019 to wind down the program, as the ten-year bull market seemed nowhere near retreating, as part of a portfolio-wide review of its active equity management program that aimed to get rid of underperforming managers and other inefficiencies. The unwinding was nearly complete as of January — in time to miss the coronavirus-induced market meltdown in March, when the S&P 500 plunged 12.5 percent for the month.

In a statement to II at the time, Meng defended the fund’s decision to end the program. “We terminated explicit tail-risk hedging options strategies because of their high cost, lack of scalability, and the fact that there are better alternatives available to CalPERS,” he said. “At times like this we need to strongly resist ‘resulting bias’ — looking at recent results and then using those results to judge the merits of a decision.”

But one of the architects of that program, who has since left the pension, has a different view.

Ronald Lagnado is a director at Universa Investments and a senior member of the firm's research group, a role he took on in March. Before that he worked as a senior investment director at CalPERS — a role previously held by Meng during his first stint at the pension.

“The Universa tail hedge would have made far more than a billion — that figure was just somebody’s estimate,” Lagnado argues. “No one has analyzed it. If the previous plan was left alone, it would have likely made $3–$4 billion. The bigger mistake Meng made was not continuing with our plan under Ted Eliopolous for significantly increasing it.”

Lagnado gives Meng credit for investigating the active management portfolio. “That was the right thing to do; a lot of that was waste, badly run and inefficient.” But he takes issue with Meng’s assertion that CalPERS had found a cheaper and better alternative to the tail-hedge program to mitigate risk, arguing that the alternative CalPERS put in place was an overly simplistic diversification attempt that would not be as effective at reducing losses in the long run as a tail-hedge program.

Tail-risk strategies have their critics. Researchers at MSCI recently argued that the big payouts they make when markets crash are more than offset by their cost. And one former CalPERS staffer says the decision to kill the program was the correct one, “because it was never going to scale to have any kind of meaningful impact on the portfolio itself.”

Lagnado maintains that this view is also too simplistic. “Universa’s strategy is scalable. There are many ways it can be deployed, and incrementally adding it moves the needle, unlike diversifying strategies,” he insists. “It doesn’t make sense to have a team of people spend years researching and building a viable strategy, observing it perform better than expected for several years, and then, with very little thought or analysis, just pull the plug. Why waste all that effort? These abrupt actions suggest a lack of experience.”

One thing everyone agrees on: The timing was wretched — and roundly criticized. Author of The Black Swan, Universa scientific adviser, and Twitter raconteur Nassim Taleb blasted the move, telling II in mid-April, “Getting rid of hedges makes no sense. Saying it does not fit an institutional investor is flawed. CalPERS is a collection of retirees getting a paycheck. You have a responsibility to those beneficiaries.”

The problems didn’t end there. Margaret Brown, a CalPERS board member and self-described watchdog, reveals that Meng didn’t tell her CalPERS had already unwound one of the two tail-hedge positions when she asked him point-blank in March how it was performing. Meeting minutes show that Meng responded, “From what we know . . . most of these strategies are performing as anticipated,” without explaining that CalPERS had exited the Universa investment.

Meng further irritated critics of the move when he said at a board meeting in late April that he would have made the same decision even if he had known the coronavirus crisis was coming.

“What you need to say is ‘Look, this is what I was looking at, this is how I evaluated, and this is why I made the decision,’” says Jelincic. “Acknowledge that the timing sucked, but don’t say I would have done it anyhow. When you say, ‘Even if I knew it was going to happen, I would have made the same choice’ — that’s just insulting.”

In June he unveiled a three-year plan to achieve the pension’s 7 percent investment return target, using what he called “better assets” — increased investments in private assets, which the pension said could deliver better expected returns relative to public markets — and “more assets,” or leverage.

Even Meng’s critics say they understand why he wanted to push the pension into riskier strategies. Meng told the board in one of his early meetings that it would need to either lower that 7 percent target — a goal that public pension managers know is about as politically expedient and achievable as relocating the sun — or accept more risk. Being told to hit that benchmark put Meng in a near-impossible position, observers say, noting that though they disagreed with his decisions to plow more money into private equity and debt, and especially to use leverage, they understood his motivation.

But others found the plan alarming.

“The City has serious concerns regarding CalPERS’ ‘Better and More Assets’ plan to achieve long-term investment returns to meet the seven percent discount rate,” wrote Pasadena city manager Steve Mermell in a letter to CEO Frost on August 3.

Mermell tells II he sent the letter out of deep concern about the proposed investment risk and the difficulty of valuing private assets.

“In California, whatever CalPERS does affects us member agencies,” says Mermell. “It’s a moral hazard situation where we bear the brunt of any bad decisions, and it’s the taxpayer that’s going to cover. The concern for us is that in order to hit their 7 percent benchmark, which is probably too high in the first place, they are going to take on additional risk. They are letting the discount rate drive their investment choices, which doesn’t seem to be the best way to approach it. The downside risk is too great.”

Mermell’s letter also expressed concern that the proposal to use upward of $80 billion in leverage on $400 billion of assets was “risky and overly aggressive,” reminding Frost that Orange County went bankrupt 25 years ago because its public pension used leverage to chase high-risk investments. But Mermell allows that there aren’t any easy answers.

“They’re in a tight spot,” he concedes. “I hear my other city managers and council people in other cities say they don’t want their contribution rates to go up,” because in California, municipalities cover the cost of administering CalPERS benefits to eligible residents. “Right now everyone’s having budget problems, so they don’t want to pay more into CalPERS. But with defined-benefit systems, you’re going to pay benefits one way or the other. They probably ought to bring the discount rate down, but then cities complain their contribution goes up. Wherever you squeeze the balloon, another bubble pops up.”

Universa’s Lagnado puts it more bluntly. “He was taking the fund on the trajectory to increase the wrong types of risk, and doing it in a way that there didn't seem to be much thought and analysis,” he says. “Abandoning their viable tail-hedge program and pushing ‘more and better assets’ as the core strategy sounds like betting on red at the roulette table.”

But Meng defended the plan in the press. “We have a plan, and we are sticking to it,” he told the FT earlier this year.

One thing is certain: Meng’s career prospects are likely damaged, at least in the short term. The pension has promoted CalPERS deputy CIO Dan Bienvenue to acting CIO while it searches for Meng’s replacement. Now it remains to be seen whether CalPERS can finally get its investment office back on track — or whether it will continue to stand in its own way because of governance problems and warring factions between management and the board.

“The hope is that they get a good leader who is politically astute, but known and proven as a CIO from an investment perspective,” says one ex-employee. “I don’t see why that’s impossible.”

Another former employee is more skeptical.

“Dan might get the job; he’s a solid guy, he knows CalPERS well, he’s a good guy and a good manager,” this person says. “He’ll take the job, but in two years he’ll leave, because it’s so painful and the governance is so toxic and they will chew through top investment people. And the portfolio will suffer because of it.”

This story has been updated to reflect comment from Charles Asubonten.