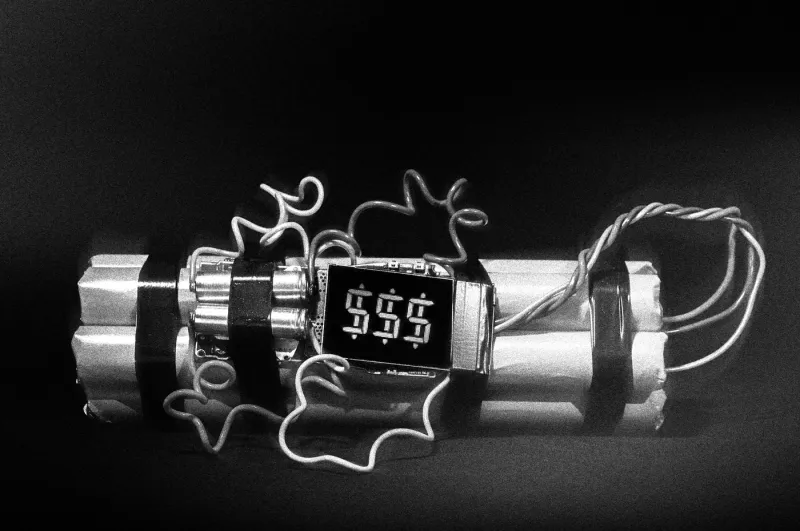

Illustration by II

Chris, I agree with your premise: Capitalism is failing a majority of market participants, and that failure is expressed as enormous inequality in the distribution of wealth in the United States.

However, I strenuously disagree that the cause of the problem is too little capitalism.

The cause of the problem is precisely runaway capitalism — too much of it. And, importantly, this capitalism-to-the-extreme is the deliberate, desired goal of the 1 percent themselves.

Also, your assessment of current business and regulatory conditions (e.g., too much government regulation) fails to understand that the neoliberal project that began in the late 1960s and early 1970s is the explicit cause of this gross economic inequality, and it misjudges the conditions.

I’d like to be specific — without being pedantic.

First, your argument is founded on an idealized — no, revisionist — definition of capitalism that the 1 percent would surely support: “At its core [capitalism] simply means that individuals should have equal rights to own capital and capital goods, and to manage those economic resources or dispose of them however they see fit, in accordance with their own personal well-being.”

What?

Capitalism is the expression of the relationship between employers and employees, in which employees create surplus value for a small group that owns capital (a.k.a. capitalists) and this surplus value (profit) is the source of this minority’s ever-increasing wealth.

Capitalism as an economic system replaced slavery and feudalism, but it merely reproduces the master/slave and lord/serf relationships in a new form: employer/employee. Like its antecedents, this is a relationship built on the creation and delivery of surplus: Employees, or workers, create surplus value for a small portion of the population who own and control capital.

I would think your historical survey of the genesis of capitalism would have led you to this definition. Yet you fail to draw the necessary conclusion.

I also find it incongruous that you write, “Only in modern times has profit maximization become the broadly accepted definition of this economic model.” Profit maximization is not a temporal phenomenon. It is an essential attribute. The goal of capitalism is the creation of surplus value, which is by definition profit maximization.

Equally problematic is your rather outrageous claim that “capitalism is freedom.” Capitalism, by its very structure, is oppressive. The competitive drive to accumulate wealth through the exploitation of human labor is the starting point for understanding capitalism — and this starting point is oppression, not freedom. Workers are wage slaves.

And at the risk of being pedantic after all, I find your appeal to Smith’s invisible hand for justification of this misaligned view of freedom to be overplayed.

You write: “And individuals free to pursue those wants and needs will do a better job of lifting their well-being collectively than can be achieved through centralized control of the means of production. This is the invisible hand that Adam Smith discussed when he wrote The Wealth of Nations.”

First, individuals are free to pursue those wants and needs only within the antagonistic struggle between employer and employee — that is, workers are free to submit themselves to a higher authority in order to exist.

Second, Smith uses “invisible hand” only three times in his corpus — once in The Wealth of Nations — and never did he write that the invisible hand is a power that makes the good of one the good of all. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith uses the term only in the context of a U.K. trader being induced to keep his capital at home.

Your definitional error and the resulting flawed claims of capitalism and freedom might have been avoided if you had situated your examination of economic inequality in the proper historical context — specifically, an experiment started 50 years ago.

Things needed to change. The owners of capital wanted to recover what was rightfully theirs. A small, elite group of capitalists, with the leaders of large corporations, made the conscious but not conspiratorial choice to start what has been described as a “political project” to protect and preserve the capitalist system.

This project is neoliberalism.

Its earliest and perhaps still most transparent expression is Louis Powell’s 1971 U.S. Chamber of Commerce memo “Attack on American Free Enterprise System,” in which the future Supreme Court justice wrote: “No thoughtful person can question that the American economic system is under broad attack. . . . The overriding first need is for businessmen to recognize that the ultimate issue may be survival — survival of what we call the free enterprise system, and all that this means for the strength and prosperity of America and the freedom of our people.”

To preserve its way of life, neoliberalism sought to limit state intervention and the power of labor via unions. And to achieve this, it needed to change elite public opinion.

This meant neoliberalism needed political power, which could be achieved by spending money on elections. This was a new tactic that brought about a shift from money in elections being necessary but modest to opening up elections to total monetization. Numerous Supreme Court cases leading up to Citizens United — which basically ruled that the expenditure of money was a form of free speech — solidified this shift.

These rulings allowed big corporations and the wealthy to dominate politics.

Neoliberalism also needed to develop and disseminate an anti-labor/pro–free market narrative. To do this it needed to control the media (which it did — an idea that is supported by your own evidence of consolidation), the pulpit (Christian evangelists adopted the message of capitalism), and the universities (in the 1960s and 1970s, they would not fall in line, so neoliberalism set up and funded an alternative: the first overtly politicized think tanks, such as the Heritage Foundation).

Surprisingly, Democratic President Bill Clinton (along with his contemporary Tony Blair) was a main agent of the neoliberal project. Though Clinton promised aggressive health care reform, he offered only failed “Hillary Care”; he promised better situations for workers but instead cooperated with business, giving us the blatantly anti-labor North American Free Trade Agreement; and he promised to “end welfare as we know it,” which he did through the punitive “Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act.” Perhaps his finest neoliberal achievement was repealing critical parts of the Glass-Steagall Act, with the support of both Republicans and Democrats.

By the 2000s the neoliberal project had achieved significant success.

Labor was disempowered.

Environmental regulation was difficult to enforce.

Financial regulation was cut back.

Taxes on the wealthy were drastically reduced.

Antitrust enforcement was neutered.

Education and health care costs skyrocketed.

The minimum wage stagnated.

These are all conditions that support and promote capitalism’s growth. Contemporaneously, there were enormous increases in social inequality across all OECD countries.

Then came the crash of 2007–8, and at least seven million households lost their homes. But even this disaster only temporarily halted the neoliberal agenda. Five years later, Warren Buffett declared victory: “Actually, there’s been class warfare going on for the last 20 years, and my class has won.”

The data supports this, as shown in a recent Bloomberg article:

As Vivek Chibber writes, “This is the view from the mansion. It is the ideology of winners, those for whom the system works fantastically well. On this view, if someone is rich it must be because of their hard work, not because they have the advantage of class; their money reflects their skills and talents, not the power they wield over workers. There is no oppression and no exploitation, only free choice and opportunity.”

You err because you fail to understand that capitalism is a fundamentally dichotomous system in which the exploitation of workers creates surplus value for a small dominant class. And you fail to recognize that a deliberate agenda — the neoliberal project — not only succeeded in saving capitalism, but also in accumulating and concentrating even more wealth and power within a small faction of the capitalist class, amplifying capitalism’s inherent inequality.

Again, I agree that “capitalism is failing a majority of market participants” (although I would use the term “people” or “workers” instead of “market participants”). In fact, I would add that it is failing everyone but the überwealthy. And I agree, we need to change this.

But this change requires the usurpation of the successful, multidecade neoliberal project, a project that is deeply entrenched in our politics, policies, regulation, laws, tax structure, and psyche. This is no easy task because it is in the self-interest of the small faction to fight hammer and tongs to preserve the status quo. As economist Gabriel Zucman recently told Bloomberg, “Once you’ve created a successful business and the wealth is established and you own billions of dollars, then what these people spend their time doing is trying to defend that position.”

More fundamentally, this usurpation requires the displacement of capitalism itself.

You are right: A redistribution of wealth will require a revolution. But this revolution cannot take the form of more capitalism because more capitalism only results in more inequality.

Now that we have properly diagnosed the problem — capitalism — we can begin to fix it.