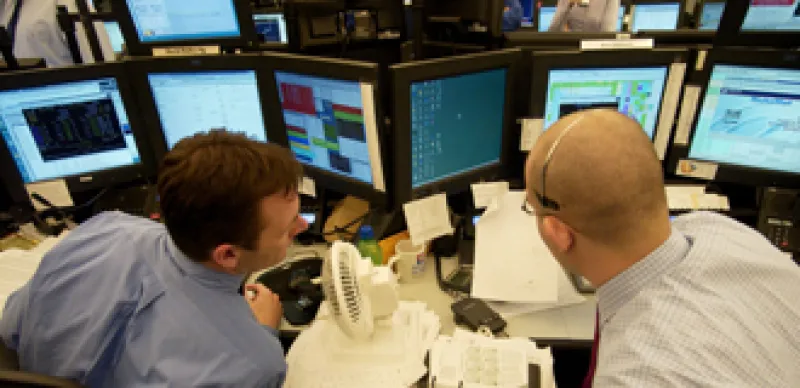

Traders work on the J.P. Morgan Chase Fixed Income and Foreign Exchange trading floor in New York on February 24, 2004. Photographer: Daniel Acker/Bloomberg News.

Daniel Acker/Bloomberg News

Traders work on the J.P. Morgan Chase Fixed Income and Foreign Exchange trading floor in New York on February 24, 2004. Photographer: Daniel Acker/Bloomberg News.

Daniel Acker/Bloomberg News