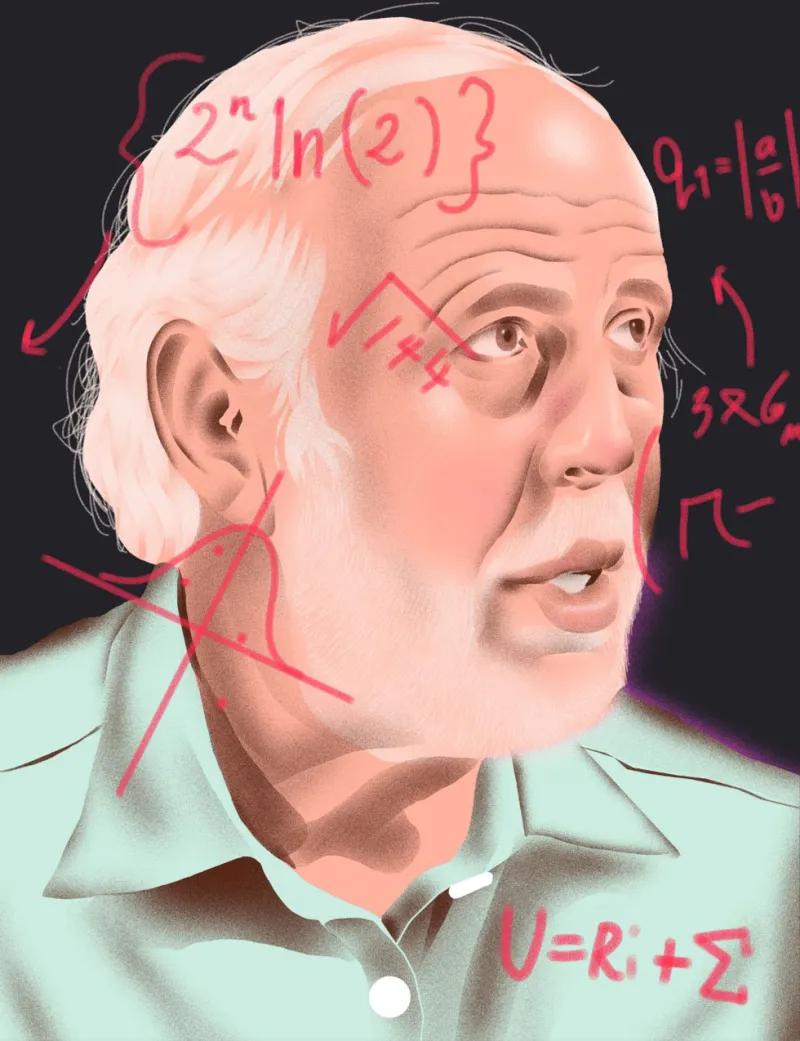

James Simons

(Illustration by Richard A. Chance)

Most people are lucky to have had one brilliant career. James Simons has had three. Born in 1938 and raised in the suburbs of Boston, the young math whiz earned a PhD in mathematics from the University of California, Berkeley and then landed a job working as a Cold War code breaker for the U.S. government. Next, he went on to build a world-class mathematics department at the State University of New York’s Stonybrook campus on Long Island.

But the endlessly restless Simons ditched his distinguished academic career to embark on a new mission: using computers to find identifiable patterns in the markets – and then trade on them.

The move baffled Simons’ fellow academics, but it paid off: Simons’ firm, Renaissance Technologies, has made him a billionaire 28 times over on the back of annualized returns of 39.1 percent net of fees in its flagship Medallion fund, according to Wall Street Journal reporter Gregory Zuckerman’s new book, The Man Who Solved the Market. But the road to success was far from smooth, and Simons endured almost unimaginable personal tragedy along the way. What follows is an excerpt of Zuckerman’s portrait of Simons, a complex, brilliant man who emerged from humble origins to become the most successful hedge fund manager of all time. -II

Four years earlier, researchers Pavel Volfbeyn and Alexander Belopolsky had quit Renaissance to trade stocks for Englander’s hedge fund, Millennium Management. Furious, Simons stormed into Englander’s office one day, demanding that he fire the traders, a request that had offended Englander.

“Show me the proof,” he told Simons at the time, asking for evidence that Volfbeyn and Belopolsky had taken Renaissance’s proprietary information.

Privately, Englander wondered if Simons’s true fear was the possibility of additional departures from his firm, rather than any theft. Simons wouldn’t share much with his rival. He and Renaissance sued Englander’s firm, as well as Volfbeyn and Belopolsky, while the traders brought countersuits against Renaissance.

Amid the hostilities, Volfbeyn and Belopolsky set up their own quantitative-trading system, racking up about $100 million of profits while becoming, as Englander told a colleague, some of the most successful traders Englander had encountered. At Renaissance, Volfbeyn and Belopolsky had signed nondisclosure agreements prohibiting them from using or sharing Medallion’s secrets. They had refused to sign noncompete agreements, though, viewing the firm as underhanded for slipping them in a pile of other papers to be signed, according to a colleague. With no signed noncompete agreement to worry about, Englander figured he had the right to hire the researchers as long as they didn’t use any of Renaissance’s secrets.

Sitting in a plush chair across from Simons that spring day, Englander said he hadn’t been privy to the details of how his hires traded. Volfbeyn and Belopolsky had told Englander and others that they relied on open-source software and the insights of academic papers and other financial literature, not Renaissance’s intellectual property. Why should Englander fire them?

Simons turned furious. He was also worried. If Volfbeyn and Belopolsky weren’t stopped, their trading could eat into Medallion’s profits. The defections might pave the way for others to bolt. There also was a principle involved, Simons felt.

They stole from me!

Evidence had begun to mount that Volfbeyn and Belopolsky may, in fact, have taken Medallion’s intellectual property. One independent expert concluded that the researchers used much of the same source code as Medallion. They also relied on a similar mathematical model to measure the market impact of their trades. At least one expert witness became so skeptical of Volfbeyn and Belopolsky’s explanations that he refused to testify on their behalf. One of the strategies Volfbeyn and Belopolsky employed was even called “Henry’s signal.” It seemed more than a coincidence that Renaissance used a similar strategy with the exact same name developed by Henry Laufer, Simons’s longtime partner.

Simons and Englander didn’t make much headway that day, but a few months later, they cut a deal. Englander’s firm agreed to terminate Volfbeyn and Belopolsky and pay Renaissance $20 million. Some within Renaissance were incensed — the renegade researchers had made much more than $20 million trading for Englander, and, after taking a break of several years, they’d be free to resume their activities. But Simons was relieved to put the dispute behind him and to send a message of warning to those at the firm who might think of following in the footsteps of the wayward researchers.

It seemed nothing could stop Simons and Renaissance.

On Friday, August 3, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted 281 points, a loss attributed to concern about the health of investment bank Bear Stearns. The drop didn’t seem like a big deal, though. Most senior investors were on vacation, after all, so reading into the losses didn’t seem worthwhile.

By that summer, a group of quantitative hedge funds had emerged dominant. Inspired by Simons’s success, most had their own market-neutral strategies just as reliant on computer models and automated trades. In Morgan Stanley’s midtown Manhattan headquarters, Peter Muller — a blue-eyed quant who played piano at a local club in his free time — led a team managing $6 billion for a division of the bank. In Greenwich, Connecticut, Clifford Asness, a University of Chicago PhD, helped lead a $39 billion quantitative hedge-fund firm called AQR Capital Management. And in Chicago, Ken Griffin — who, in the late 1980s, had installed a satellite dish on his dormitory roof at Harvard to get up-to-the-second quotes — was using high-powered computers to make statistical-arbitrage trades and other moves at his $13 billion firm, Citadel.

On the afternoon of Monday, August 6, all the quant traders were hit with sudden, serious losses. At AQR, Asness snapped shut the blinds of the glass partition of his corner office and began calling contacts to understand what was happening. Word emerged that a smaller quant fund called Tykhe Capital was in trouble, while a division of Goldman Sachs that also invested in a systematic fashion also was suffering. It wasn’t clear who was doing the selling, or why it was impacting so many firms that presumed their strategies unique. Later, academics and others would posit that a fire sale by at least one quant fund, along with abrupt moves by others to slash their borrowing — perhaps as their own investors raised cash to deal with struggling mortgage investments — had sparked a brutal downturn that became known as “the quant quake.”

During the stock market crash of 1987, investors were failed by sophisticated models. In 1998, Long-Term Capital saw historic losses. Algorithmic traders braced for their latest fiasco.

“It’s bad, Cliff,” Michael Mendelson, AQR’s head of global trading, told Asness. “This has the feel of a liquidation.”

For most of that Monday, Simons wasn’t focused on stocks. He and his family were in Boston following the death and funeral of his mother, Marsha. In the afternoon, Simons and his cousin, Robert Lourie, who ran Renaissance’s futures-trading business, flew back to Long Island on Simons’s Gulfstream G450. Onboard, they learned Medallion and RIEF were getting crushed. Simons told Lourie not to worry.

“We always have very good days” after difficult ones, he said.

Tuesday was worse, however. Simons and his colleagues watched their computer screens flash red for no apparent reason. Brown’s mood turned grim.

“I don’t know what the hell is going on, but it’s not good,” Brown told someone.

On Wednesday, things got scary. Simons, Brown, Mercer, and about six others hustled into a central conference room, grabbing seats around a table. They immediately focused on a series of charts affixed to a wall detailing the magnitude of the firm’s losses and at what point Medallion’s bank lenders would make margin calls, demanding additional collateral to avoid selling the fund’s equity positions. One basket of stocks had already plunged so far that Renaissance had to come up with additional collateral to forestall a sale. If its positions suffered much deeper losses, Medallion would have to provide its lenders with even more collateral to prevent massive stock sales and losses that were even more dramatic.

The conference room was close by an open atrium where groups of researchers met to work. As the meeting continued, nervous staffers studied the faces of those entering and leaving the room, gauging the level of desperation among the executives.

Inside, a battle had begun. Seven years earlier, during the 2000 technology- stock meltdown, Brown didn’t know what to do. This time, he was sure. The sell-off wouldn’t last long, he argued. Renaissance should stick with its trading system, Brown said. Maybe even add positions. Their system, programmed to buy and sell on its own, was already doing just that, seizing on the chaos and expanding some positions.

“This is an opportunity!” Brown said. Bob Mercer seemed in agreement.

“Trust the models — let them run,” Henry Laufer added.

Simons shook his head. He didn’t know if his firm could survive much more pain. He was scared. If losses grew, and they couldn’t come up with enough collateral, the banks would sell Medallion’s positions and suffer their own huge losses. If that happened, no one would deal with Simons’s fund again. It would be a likely death blow, even if Renaissance suffered smaller financial losses than its bank lenders.

Medallion needed to sell, not buy, he told his colleagues.

“Our job is to survive,” Simons said. “If we’re wrong, we can always add [positions] later.”

Brown seemed shocked by what he was hearing. He had absolute faith in the algorithms he and his fellow scientists had developed. Simons was overruling him in a public way and taking issue with the trading system itself, it seemed.

On Thursday, Medallion began reducing equity positions to build cash. Back in the conference room, Simons, Brown, and Mercer stared at a single computer screen that was updating the firm’s profits and losses. They wanted to see how their selling would influence the market. When the first batch of shares were sold, the market felt the blow, dropping further, causing still more losses. Later, it happened again. In silence, Simons stood and stared.

Problems grew for all the leading quant firms; PDT lost $600 million of Morgan Stanley’s money over just two days. Now the selling was spreading to the overall market. On Thursday, the S&P 500 dropped 3 percent, and the Dow fell 387 points. Medallion already had lost more than $1 billion that week, a stunning 20 percent. RIEF, too, was plunging, down nearly $3 billion, or about 10 percent. An eerie quiet enveloped Renaissance’s lunchroom, as researchers and others sat in silence, wondering if the firm would survive. Researchers stayed up past midnight, trying to make sense of the problems.

Are our models broken?

It turned out that the firm’s rivals shared about a quarter of its positions. Renaissance was plagued with the same illness infecting so many others. Some rank-and-file senior scientists were upset — not so much by the losses, but because Simons had interfered with the trading system and reduced positions. Some took the decision as a personal affront, a sign of ideological weakness and a lack of conviction in their labor.

“You’re dead wrong,” a senior researcher emailed Simons.

“You believe in the system, or you don’t,” another scientist said, with some disgust.

Simons said he did believe in the trading system, but the market’s losses were unusual — more than twenty standard deviations from the average, a level of loss most had never come close to experiencing.

“How far can it go?” Simons wondered.

Renaissance’s lenders were even more fearful. If Medallion kept losing money, Deutsche Bank and Barclays likely would be facing billions of dollars of losses. Few at the banks were even aware of the basket-option arrangements. Such sudden, deep losses likely would shock investors and regulators, raising questions about the banks’ management and overall health. Martin Malloy, the Barclays executive who dealt most closely with Renaissance, picked up the phone to call Brown, hoping for some reassurance. Brown sounded harried but in control.

Others were beginning to panic. That Friday, Dwyer, the senior executive hired two years earlier to sell RIEF to institutions, left the office to pitch representatives of a reinsurance company. With RIEF down about 10 percent for the year, even as the overall stock market was up, customers were up in arms. More important for Dwyer: He had sold his home upon joining Renaissance and invested the proceeds in Medallion. Like others at the firm, he had also borrowed money from Deutsche Bank to invest in the fund. Now Dwyer was down nearly a million dollars. Dwyer had battled Crohn’s disease in his youth. The symptoms had abated, but now he was dealing with sharp aches, fever, and terrible abdominal cramping; his stress had triggered a return of the disease.

After the meeting, Dwyer drove to Long Island Sound to board a ferry to Massachusetts to meet his family for the weekend. As Dwyer parked his car and waited to hand his keys to an attendant, he imagined an end to his agony.

Just let the brakes fail.

Dwyer was in an emotional free fall. Back in the office, though, signs were emerging that Medallion was stabilizing. When the fund again sold positions that morning, the market seemed to handle the trades without weakening. Some attributed the market’s turn to a buy order that day by Asness of AQR.

“I think we’ll get through this,” Simons told a colleague. “Let’s stop lightening up.” Simons was ordering the firm to halt its selling.

By Monday morning, Medallion and RIEF were both making money again, as were most other big quant traders, as if a fever had broken. Dwyer felt deep relief. Later, some at Renaissance complained the gains would have been larger had Simons not overridden their trading system.

“We gave up a lot of extra profit,” a staffer told him.

“I’d make the same decision again,” Simons responded.

From THE MAN WHO SOLVED THE MARKET: How Jim Simons Launched the Quant Revolution by Gregory Zuckerman, published by Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Gregory Zuckerman.