One way for investors to protect themselves against sexual harassment scandals at asset managers is through contracts.

“Obviously the topic of sexual assault and harassment is front and center nowadays,” says Gregg Buksbaum, partner at Squire Patton Boggs’ private investment group. “Perhaps this is something that may start to find its way into contracts with more specificity.”

Buksbaum’s colleague Geoffrey Davis says he sees institutional investors — particularly government pension plans and foundations — increasingly seeking to invest based on their values. This has included environmental, social, and governance-driven investing, as well as opt-out provisions written into contracts for investors who may have moral qualms with investing in companies that offer alcohol or gambling. “There’s a tension between social change and investing,” Davis says.

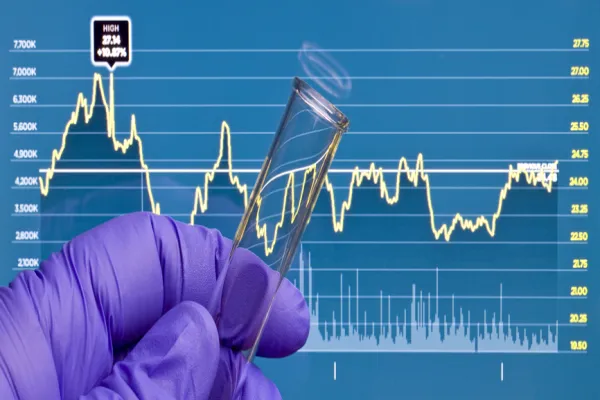

For asset managers, adjusting to these values may be imperative. According to a 2016 study from the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, one in four women say they have been harassed in the workplace. The case of Samuel Isaly, founder of biotech hedge fund OrbiMed Advisors, who has been accused of harassment by several women, would be just one example of this behavior. A spokesperson for Isaly said he denies the allegations, and OrbiMed said in December that Isaly was stepping down as a result of succession planning. A spokesperson for OrbiMed said via email that Isaly’s retirement process is nearing completion.

For investors worried about cases of sexual harassment and assault, there are contractual options.

One way so-called limited partners — the investors who commit capital to funds managed by private equity and hedge fund firms — can redeem their money is through a disabling clause, according to Buksbaum. “What is the actual trigger for an investor to liquidate or kick out the general partner?” he asks. “Oftentimes any of these bad acts are subject to final, non-appealable authority.” Translation: A case against a general partner who has committed a crime has to wind its way through the court system until a final judgment is made that cannot be appealed. Only then can a limited partner liquidate or fire that fund firm, says Buksbaum.

Given that sexual assault, rape, and sexual harassment can be considered crimes, this provision offers a way for investors to hold general partners accountable. But it could take a long time for a court case to make it through the system, Buksbaum says. Another way for limited partners to curb bad behavior is through disclosure covenants. “A half-step investors can take is to ask for notification of any allegations of behavior of that type,” Davis says. “That’s harder for the manager to resist in contract negotiations and it makes them conscious of the behavior.”

To be sure, this isn’t an airtight method of prevention for limited partners. It does, however, Davis notes, put sexual harassment and assault on the minds of general partners. “At the end of the day, it’s a contractual negotiation,” Buksbaum says. “There’s no universal standard.” One problem investors may run into with these provisions, according to Buksbaum and Davis, is that a firm may still have a culture that fosters the type of behavior an employee has been ousted for perpetrating. In the case of OrbiMed, many of the women who discussed Isaly’s pattern of harassment pointed to staff who allegedly did little to change his behavior, according to health-care-focused news site Stat.

“Occasionally you have more seismic events where the market reacts very quickly,” Buksbaum says. During the financial crisis, hedge funds responded quickly to concerns over the Bernard Madoff Ponzi scheme, he says, after investors requested firms become more transparent and alert them to investigations. But there hasn’t really been a sexual assault scandal in asset management that has Madoff-level implications.

“If there were a notorious case where a big private-equity firm leader got canned, that would draw everyone’s attention to the abject risk,” says Davis. “There are famous actresses who can immediately impact how the industry operates,” he says. “I don’t know if there are parallels in private equity. Do women have that same power?”