The first issue of Institutional Investor, published in 1967, provides the earliest written record of the U.S. asset management industry. Unbeknownst to any reader at the time, it also contains the seeds of a scandal — one whose underlying causes persist today.

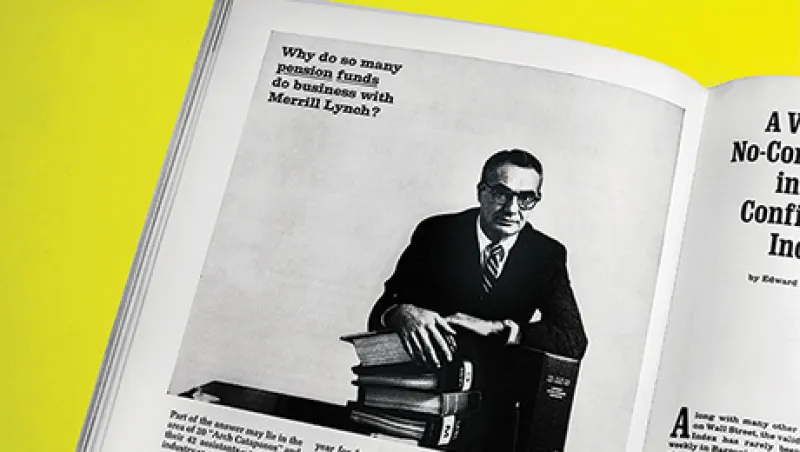

A review of the issue revealed some interesting artifacts (my favorite: “The Case for Front-End Loads”). However, it’s an advertisement — for Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith — that reveals “prehistoric” evidence of the structural misalignment between asset managers and clients.

Initially and unsuspectingly, I was drawn to the ad because of its headline: “Why do so many pension funds do business with Merrill Lynch?” (The emphasis is from the original.)

Pension funds struck me as an odd target. In 1967, U.S. defined benefit assets (DC plans would come on the scene in 1981) totaled about $150 billion; few funds allocated to equities, and fewer still managed assets internally.

Then my interest shifted from the headline to the ad’s message, which touted the value of Merrill ’s industry analysts. Specifically, the firm presented Arch Catapano — its aerospace analyst — as its exemplar. Though the ad describes Catapano’s research methodology in words similar to those used for II’s current All-America Research Team aerospace analyst, Ron Epstein, what really caught my attention was the picture of Catapano. His posture and visage genuinely made me believe the claim that “. . . when it comes to the aerospace industry, we count on Arch to supply [in-depth research].”

I looked further into Catapano and discovered that you could, indeed, count on him for in-depth research; the SEC would later investigate him, his employer, and numerous colleagues for insider trading.

In August 1968 the SEC ordered an administrative proceeding, alleging that in June 1966 Merrill’s research department had passed confidential, price-sensitive information to its institutional brokerage clients. Before the underwriting of a new convertible debenture by Douglas Aircraft (a predecessor of McDonnell Douglas), Douglas officials notified an employee in Merrill’s underwriting group that it would experience a “significant deterioration” in earnings. Following the then-existing Merrill communication policy, this employee passed the negative earnings information to a research executive in the New York institutional sales office — none other than our man Catapano.

According to SEC documents, Catapano “acknowledged the help the information provided in developing his knowledge and understanding of Douglas’s affairs, and agreed not to discuss the information with anyone outside of Merrill Lynch and with no one inside the firm” except two specifically named colleagues. “Ignoring his commitment, Catapano acquainted his assistant, Carol Neves, and Phillip Bilbao, then head of Merrill Lynch’s Institutional Services Department, with the earnings data.”

At this point the dam broke: The SEC claimed that Catapano and some colleagues had shared the negative news with “a small number of institutional investors” who were interested in Douglas’s stock even as Merrill was advising other investors to buy the stock.

In November 1968, Merrill consented to penalties including public censure, the temporary closing of two operations, and the censure of ten executives, including Catapano. (This enforcement action did not spell the end of Catapano’s career at Merrill; a 1975 New York Times story reported that “Arch J. Catapano, who heads fundamental research at Merrill Lynch, is the man who recruited the star analysts.”)

The story only gets better from here. The “institutional investors” who were the alleged recipients and beneficiaries of the Douglas information were not the aforementioned pension funds — in fact, we might presume they were among the clients being told to buy Douglas — but Merrill’s asset management clients, including a group of hedge funds.

Yes, there were hedge funds in 1967. Although no definitive directory exists, a 1970 Fortune article gave a “wobbly” estimate of 150 hedge funds managing $500 million.

Merrill’s clients were not just any hedge funds, however. In aggregate, they managed more than half of all hedge fund assets and included two founded by A.W. Jones, the father of hedge funds, and six other funds that traced their lineage to Jones: City Associates; Fairfield Partners, co-founded by Barton Biggs; three partnerships affiliated with John Hartwell, who was the subject of a praiseworthy portrait in II’s first issue; and Fleschner, Becker Associates, whose principals had been Jones’s brokers (and who later would be involved in what some call the first hedge fund blowup).

By June 1970, the SEC had censured all of them.

The Douglas Aircraft controversy is not just another case of hedge funds using inside information for their own benefit. It was also the earliest known enforcement case involving hedge funds, the first insider trading case in which hedge funds were implicated, the first class action against a hedge fund, and the first use of the term “tippees” to designate parties that receive inside information. More generally, the case spurred the SEC to investigate ways to regulate hedge funds and register the general partners.

The case is also significant because it serves as the historical archetype of the structural asymmetry between asset managers and asset owners — an asymmetry that persists today. The ad proclaims Merrill’s commitment to pension funds, yet the firm was apparently acting against the funds’ best interests. The ad’s final sentence reads: “When Arch Catapano has something to say about the aerospace industry . . . we think it makes good sense for any pension fund to listen.”

And, apparently, do the opposite. What’s worse, that advice is often still valid today.