"WHEN I'M LOSING MONEY THIS YEAR, I FEEL BAD," ONE New York–based global macro trader groused to me recently. “When I’m making money this year, I don’t know why I’m making money, so I still feel bad — though not quite as bad.” He shook his head at the confusion and complexity of financial markets since January: “Risk assets have been up and down and all over the place.”

This trader is not alone. It’s been a hard year for most investors. By the end of the summer, the mean return of the diversified macro hedge funds tracked by HSBC Private Bank’s alternative-investment group was a modest 2 percent, with an average volatility of 10 percent. The mean return smooths over some gut-wrenching swings in the sample, with one out of ten funds having an annualized volatility of more than 15 percent; three out of ten had year-to-date losses of almost 20 percent.

The market for Ferraris is less volatile than hedge fund returns. Last month the Ferrari dealership at Park Avenue and 55th Street arranged four gleaming new models on its sidewalk, which was adorned with red carpets and klieg lights for New York’s Fashion Week. A number of chic young ladies, taller and thinner than I am, were sipping champagne and chatting amiably, some in Italian, around the cars. So of course I asked the saleslady the price and delivery schedule for a cherry red (rosso maranello) Ferrari FF.

“The base price is $295,000,” she replied evenly.

“Are you seeing a drop-off in demand as the investment bankers and traders are having a hard time this year?” I inquired.

“Not really,” she said. “The lead time is still two years.”

“Uh, what about that bianco Italia Ferrari California over there?” I asked.

She brightened: “$195,000 and just a six-month wait. Interested?” I gave her my Princeton University professor business card and watched as she wrote me off as a prospect.

Six months may be a short time for Ferrari, but it can be an eternity in the hedge fund world. At roughly half year intervals, I’ve been polling two dozen macro traders on the so-called reference scenarios of the global economy, the big drivers that move financial markets.

In June 2011, I described a consensus on the four key scenarios — U.S. monetary policy, Chinese growth, the euro zone debt crisis and oil prices — that emerged from a conference of policy wonks and macro traders at the Ditchley Park country manor in Oxfordshire, England (Institutional Investor, June 2011). In January we revisited the reference scenarios and the odds that the traders attached to the various outcomes (Institutional Investor, January 2012). I repolled the traders in August, convening some of them — those who were not sipping white wine in the Hamptons — at Manhattan’s Lotos Club. If Ditchley Park’s Elizabethan elegance could double as Downton Abbey, the Lotos Club’s Upper East Side 19th-century mansion could be a stage set for Edith Wharton’s Age of Innocence.

Although we are sampling the scenario at fairly long intervals, there is underlying continuity in the drivers. No surprise there. After all, these drivers are proxies for economic growth in the four major markets: the U.S., Europe, China and the Middle East. The formulation of the drivers and the alternative outcomes have transformed over time in subtle and interesting ways. So have the odds that traders attach to the outcomes — not just the mean values but also the standard deviations of the predictions, which is the best measure of dispersion and uncertainty on the part of the traders.

Today the primary driver for our traders is the U.S. economy — notably, whether it will fall off a fiscal cliff in 2013 — followed by the euro zone crisis, Chinese growth and the chaos in Syria. The last factor (can the upheaval be contained, or will it spill over into a wider conflict, including a proxy war involving Iran?) has been pushing up the spot oil price over the past three months.

Over the last year our macro traders have become more worried about fiscal deficits and central bank money-printing everywhere. They now believe that QE repeats are baked in at the Fed, and that the odds of fiscal rectitude in Washington are no better than even. They are more pessimistic about Chinese growth prospects, even as the People’s Bank of China is opening the credit taps, but more optimistic that the euro zone will muddle through thanks to European Central Bank intervention. As real growth prospects dim and the odds of supply constraints slim, they are more confident that Brent crude oil prices will slide below $100 a barrel.

IN AUGUST OUR GLOBAL MACRO TRADERS overwhelmingly assumed that Federal Reserve Board chairman Ben Bernanke was going to embark on a third round of quantitative easing because unemployment had stayed stubbornly high (although they remained dubious about its effectiveness in stimulating growth). They were right. Bernanke signaled QE3 in his Jackson Hole, Wyoming, speech at the end of August and confirmed it after the Federal Open Market Committee meeting on September 13.

What really troubles the traders is how far Washington could fall off the fiscal cliff at the end of this year, when a panoply of spending cuts and tax increases is scheduled to take effect.

Stunning, at least to me, is that our traders’ mean forecast of a fiscal free fall is 45 percent. They assign a mean value of only 55 percent to the prospect of Democrats and Republicans working out a fiscal grand bargain, with a standard deviation of 21. One of the traders assigned a 75 percent probability of no bargain. The trader who was most confident about a grand bargain still assigned a one in five chance that the U.S. would go off the cliff.

In contrast, a recent Goldman Sachs Group report assigned a one in three chance of a fiscal calamity, citing a survey of its clients that put the risk at only 17 percent. Why are our traders so pessimistic?

Let’s look first at the math. Going over the fiscal cliff would deal the economy a $600 billion blow, worth 4 percent of GDP, in 2013. Democrats and Republicans pretty much agree on the need to avoid such a drastic fiscal tightening given the weakness of the economy; better to attack the deficit over the medium term. But they disagree strongly on the political calculus: Should the deficit be slashed by reducing spending or increasing taxes?

Two thirds of the scheduled $600 billion hit in 2013 will come from increased taxes. Unless Congress takes action, the top personal tax rate will zoom from 35 percent to 39.6 percent. The payroll tax also will go way up, from 4.2 percent to 6.2 percent.

The next biggest piece of the fiscal hit is federal spending cuts: $110 billion a year. This is the “sequestration” part of the Budget Control Act of 2011. Sequestration kicks in if Congress can’t agree on a package of expenditure cuts. And because entitlements, which are “mandatory spending” in Washington-speak, are exempt from sequestration, half of the cuts fall on the Department of Defense, which is “discretionary spending.” Says Thomas McGlade, portfolio manager and head of U.S. operations for London-based hedge fund firm Prologue Capital, “The sequestration methodology for resolving the budget crisis of 2011 was a depressing abdication of congressional responsibility to govern.”

Whether or not we go over the edge is a matter of pure politics, according to our traders. When and how deep that cliff dive goes is in the hands of the Republican and Democratic congressional leaders. The Democrats want more revenue to cover government expenditure, which they do not wish to shrink. The Republicans want to shrink expenditure and are dead-set against raising taxes. Not a lot of room to square this particular circle.

Good-government scholars and think tank policy wonks decry the fiscal cliff because it doesn’t solve the long-term structural problem of the fiscal deficit. The new revenue comes from higher tax rates; it doesn’t broaden the tax base by eliminating distortions, special breaks or other so-called tax expenditures that are buried in the big deduction line items. The expenditure reductions come from the discretionary budget, including defense. They don’t reduce the mandatory expenditures in entitlements such as Medicare and Medicaid, which are growing faster than the underlying economy and will break the budget, unless rising interest expense on the $15.9 trillion national debt breaks it first.

But good-government scholars and think tank policy wonks don’t make tax and spending decisions. Our elected representatives and our president do.

The Democrats wrapped their desire for more revenue to cover growing government expenditure in “tax the millionaires” rhetoric, which in turn was tied to a neo-Keynesian argument of countercyclical fiscal stimulus.

The Republicans were counting on fiscal deficits to constrain spending, but it didn’t work out that way. The GOP resisted any tax increases, fulfilling the pledge it made to antitax lobbyist Grover Norquist. As a result, Republican lawmakers find themselves facing the prospect of an extremely distasteful slashing of defense on the expenditure side. Senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham went on the road this summer to decry the awful impact of these defense cuts on national security.

All summer there has been much talk of a grand bargain on Capitol Hill involving some combination of spending cuts and tax increases. But in the view of longtime Washington watchers and most of our gimlet-eyed traders, that is so much talk show chaff. “Some Democrats will be happy to drive over the fiscal cliff,” Ed Rollins, who managed Ronald Reagan’s victorious 1984 presidential campaign, told our group of traders over dinner at the August Lotos Club meeting. “The fiscal cliff dive increases taxes in ways they like and cuts expenditure in ways they enjoy. The Democratic leadership in the House and Senate know they’d never get the votes to cut back on defense expenditure this much.”

Though they may wring their hands publicly, Rollins said, both House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi and Senate leader Harry Reid would probably throw themselves into the sequestration chasm to reduce defense expenditure by such a big amount for such an extended period of time. “So the Democratic leadership doesn’t want a grand bargain but will just go through the motions,” concluded Rollins.

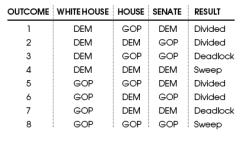

The Republicans are coming to the realization that they’ve been outfoxed strategically, but they are so boxed in by the “no new taxes” pledge that a grand bargain is off the table. They too will go through the motions, and that’s it. Neither House Speaker John Boehner nor Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell will risk getting too far ahead of his troops on this score. There simply is no grand bargain in the cards in 2012 for the current 112th Congress, not in the run-up to the November elections and not when they come back for the marvelously termed lame-duck session after the election. If Rollins is correct, the fiscal cliff driver depends upon what happens on Election Day. Only three big outcomes count: who wins the White House, which party controls the Senate and which party controls the House. There are only eight possible combinatorial outcomes:

As Rollins and all Washington insiders remember viscerally, outcomes No. 3 and No. 7 are the famous deadlock outcome, in which the president faces off against a Congress entirely opposed to him. Outcomes No. 4 and No. 8 are a sweep in which the president and both houses of Congress are on the same side. The rest are different flavors of divided government.

The global macro traders believe that only four of these outcomes could produce a fiscal rebalancing in the U.S., by some combination of increased taxes and reduced expenditure. A sweep by either party would break the deadlock. A party that controlled both the White House and the House of Representatives (which initiates the budget) would be able ultimately to prevail with its fiscal program.

For example, in the case of a Democratic sweep (outcome No. 4), with Barack Obama returned to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, they see a very Democratic kind of fiscal bargain relying largely on tax hikes to match their social expenditure plans and a smaller defense budget. By the same token, in a Republican sweep (outcome No. 8), the Republicans in Congress could fashion their own deal consisting of cuts in social spending (though not too much trimming at the Pentagon) and a few judicious tax increases, packaged as “tax reforms.”

A grand bargain would be harder in a divided government in which the White House and the House of Representatives were working together against an obstructing Senate, but still likely.

So what is the probability that we fall off the cliff at the start of 2013?

Under almost any set of circumstances, the 113th Congress will feature even more fiscally conservative Republicans. “The Tea Party is going to expand its influence,” predicts Rollins. “Texan Ted Cruz and Indiana’s Richard Mourdock, if elected, won’t enter the Senate chamber with fiscal compromise as their first order of business.”

On Intrade, an online prediction market, an Obama win of the White House was trading late last month at the equivalent of 72.5 percent, sustained Republican control of the House at 73 percent. With similar reasoning, the traders in our poll trimmed their decision tree to outcomes No. 1, No. 3, No. 5 and No. 8. Little surprise, then, that their mean odds came out as 45 percent over the cliff, 55 percent a fiscal bargain.

Looking back to previous reference scenarios and the sequential probabilities assigned by our traders, there is an interesting evolution of their faith in the U.S. government’s fiscal responsibility and a consistent though sometimes despondent faith in the Fed’s persistence in printing money to stimulate the economy.

The June 2011 Ditchley reference scenario posed a choice between a “business as usual” outcome with continued fiscal deficits and QE on one hand and a “painful” fiscal adjustment (some flavor of a grand bargain, in retrospect) and no more QE on the other. Our traders assigned a mean probability of 0.32 to the business-as-usual outcome and 0.68 to adjustment. They were wrong, on average, as it turned out. There was no fiscal adjustment in 2011.

With this painful lesson under their belts, our traders were looking closely at the odds of sustained QE at the end of 2011, and the mean prediction was 70 percent that 2012 would see more Fed debt buying. The majority view was that the Obama administration would continue to run deep deficits in 2012 and that the Fed would help it do so by funding the Treasury. They were right, on average, as it turned out.

Now the traders are assuming that QE is with us for an indeterminate time but that there is a 55 percent chance, on average, that the fiscal cliff will force rectitude on the U.S. government in 2013. We shall see.

GLOBAL MACRO TRADERS RARELY place direct bets on China’s GDP numbers, but Chinese growth expectations drive a whole series of other assets, ranging from the Australian dollar to Brazilian mining stocks. With the euro zone flat (zero growth in the first quarter, – 0.2 percent in the second) and the U.S. economy expanding only sluggishly, all hopes for global growth in 2013 are fixed on Beijing.

The Chinese are intently aware of their pivotal role in global growth. An ironic refrain has been making the rounds in Beijing ever since the financial crisis:

1949: Communism saves China

1979: Capitalism saves China

1989: China saves Communism

2009: China saves Capitalism

The average odds our traders have assigned to China achieving a 7.5 percent growth rate have slowly trended down, from 57 percent in June 2011 to 53 percent in December to 50 percent now. The standard deviation in that prediction has ticked up from 19 to 23 to 25.

That growth target is loaded with meaning for both the Communist Party of China and global macro traders. They all know that an expansion below that pace will cause unemployment to swell, with all the associated political risks. According to Ken Miller, longtime China watcher and former vice chairman of Credit Suisse First Boston: “When China gave up the 8 percent bogie for their growth target, they were really saying all bets are off. Eight is the lucky number in China, a target which in the past they could always exceed.”

The party apparat in Beijing is justifiably nervous about falling below the 8 percent level given the implicit deal in China in which the party monopolizes political power in exchange for delivering economic growth. The leadership is particularly sensitive to the growth and unemployment figures in the run-up to the 18th Party Congress this month, when President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Wen Jiabao are due to smoothly hand over the reins, respectively, to Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang.

At least, that was the script earlier this year. That was before the scandals surrounding Bo Xilai and his wife, Gu Kailai, became public and the scale of brutal infighting and truly massive corruption within the party elite was revealed. Prosecutors alleged that British consultant Neil Heywood was poisoned after arguing with Gu over his fee for helping her move money offshore. According to the diplomatic chatter in Beijing, the amounts involved ran into the hundreds of millions of dollars. This is sizable money laundering, not just a squabble over an apartment or two in Knightsbridge, as was reported when the scandal first broke. We are talking Ferrari sums of money here. A lot of black money is flowing through the fingers of the families of the party leadership.

Bo’s playboy son, Bo Guagua, allegedly pulled up in a red Ferrari in front of the U.S. ambassador’s residence in Beijing to take the diplomat’s daughter out on a date. (Bo fils denied this.) More salaciously, the son of Ling Jihua, director of the general office of the Communist Party’s central committee, died earlier this year after crashing his black Ferrari 458 Spider on a Beijing ring road. The South China Morning Post asserted that “Ling was half-naked when the crash occurred and his two passengers were naked or half-dressed, suggesting they had been involved in some kind of high-speed sex game.”

What does all this mean for the real growth figure? “It’s enough to make us yearn for the sedate pabulum of the 17th Party Congress,” a Beijing-based diplomat complains to me. “With all this infighting and scandalmongering, everyone has his or her head down. Including the technocrats and the statisticians.”

China’s very competent macro managers have always had to deal with a high degree of uncertainty about the political jockeying that goes on in the country, but recent events present a new level of murkiness.

Some see this as an inflection point at which Beijing could resort to its usual game plan of turning on all the spigots to stimulate domestic investment in real estate or infrastructure by a combination of directed bank lending and administrative fiat. Or Beijing could decide to allow some of the hard structural transformations to take place that will eventually allow consumption and market-led investment to replace the so-called command sectors.

To boost GDP in the short term, which means 2013, Beijing will have to turn its back on structural reforms and go for growth. Over the past 18 months, officials have deliberately slowed the real estate bubble through a range of policies. What they slowed, they can start up again, but only at the price of reverting to the quasi-command-policy armamentarium that everyone agrees is coming up against some hard math. According to China watcher Miller, “They are going to have to be the Sullenbergers of command economies to bring this baby in for a soft landing.”

The data isn’t encouraging. Over the past 24 months, the growth in industrial production has gradually slowed, from the 15 percent range down to 9 percent in August. Sell-side analysts are perusing every single statistic they can get their hands on — ranging from things like electricity consumption to piles of shipping containers and coal in seaports — to get a handle on real underlying economic activity. They don’t trust the official data, and they don’t feel they have much visibility into the real economic decision-making process in Beijing. Those waters, already murky, have become even muddier in the run-up to the party Congress.

“I think China will likely maintain above 7.5 percent growth, because the government has a number of cards to play, including monetary policy adjustment, tax cuts, wage increases, subsidizing green consumption, the renovation and technological upgrade of factories and lifting some restrictions on investment,” says Cheng Li, research director at the Brookings Institution’s John L. Thornton China Center. “We will more likely see unity rather than infighting over economic policy in the new leadership in the early months after the transition, barring something entirely unforeseen, like a military clash with Japan or in the South China Sea.

“The decision-making process, the collective approach to policymaking on the Standing Committee [of the Politburo], will be similar to that of the Hu-Wen administration, but the personality will be quite different,” Li adds. “They may change the style and tone of communications to both the Chinese public and the international community.”

Other observers are less confident of smooth, unified decision making. “Unity at the top in Beijing is a phenomenon of the past that will be elusive in the future,” says Bonnie Glaser, a China scholar at Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies. “With China’s state-run resource companies, financial institutions, local governments, media and other interest groups all vying for influence and China’s domestic challenges mounting, can we really expect more of the same? I believe China is approaching an inflection point. Economic and political reforms are desperately needed, and only a strong leader will be able to shake up the system. Let’s hope that Xi Jinping has greater bureaucratic skill and leadership abilities than Hu Jintao. China can no longer simply muddle through.”

THE NOTION OF MUDDLING through has resonance in Brussels as well as in Beijing. The issue for the euro zone isn’t whether to expel Greece, say most of our traders. The question is whether the euro zone can continue to “extend and pretend,” through a combination of bailout money and European Central Bank accommodation, for a further six months without a run on the banking system and a panic in the sovereign debt markets.

In June 2011 the average bet at our Ditchley Park proceedings was 53 percent that the euro zone could extend and pretend with no involuntary haircuts on private sector bondholders. The traders who subsequently went long Greek sovereigns had an unpleasant fall as the European Union imposed haircuts on debtholders at German insistence. Sovereign risk spreads between Spanish and Italian debt on one hand and German Bunds on the other continued to widen.

By this August the average bet continued at 53 percent for extend and pretend. I noticed that traders in London and New York were distinctly more pessimistic than those closer to Brussels and Frankfurt. Part of this reflects the consistent skepticism of English-language publications such as the Economist, the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal. In the view of Graham Bishop, a London-based euro zone analyst, “The City is just beginning to realize that euro zone political leaders really plan to take extend and pretend to its logical conclusion: more Europe in the form of a fiscal union or federation of nation states.”

Another part of this skepticism stems from the unwieldy decision-making mechanisms of the euro zone, which make it hard to pull off the chain of events needed for extend and pretend. For example, in early 2012 one London-based trader traced out for me on a whiteboard the steps that would be required “to keep Spanish government debt markets from melting down in slow motion,” as he put it. “First, somebody has to figure out how much bad debt the Spanish banks really have from the property bubble. Then these banks have to be shut down or recapitalized. The recap funds have to come from the European Stability Mechanism, but Spain has to ask for them first and accept some conditions they won’t like. Then Spain has to come up with an austerity budget — lots of luck there, with the provinces squabbling with Madrid. Meanwhile, the European Union needs to set up an ESM program, the Germans have to approve it, Madrid has to ask for sovereign debt assistance, the ESM will ask for conditions, the Germans have to approve both the debt and the conditions, and the ECB has to intervene enough to keep the yields under control. Got it?”

Even as the trader assigned relatively high probabilities to each branch of the decision tree, the compound probability of the whole chain actually playing out that way got smaller and smaller. By the final branch his calculated probability was just 50-50. I left his Mayfair office with a clearer sense of the arboreal density of the decision tree but with zero confidence that I could predict the outcome. Fifty-fifty is a coin toss — not much of a prediction and not very helpful in trying to design a trade in the real world.

As it turned out, several of those branches did in fact break in favor of extend and pretend. By mid-August our traders became more optimistic, assigning a mean probability of 65 percent that Brussels, the ECB and the European Stability Mechanism could keep it all together. This was shaped in large part by ECB president Mario Draghi’s July announcement that the bank would do “whatever it takes” to keep the euro intact. This optimism was buoyed even more by Draghi’s comments after the August 2 ECB meeting, when he explained that the bank would undertake open market operations to purchase shorter-dated peripheral bonds, provided the countries concerned agreed on an ESM assistance program with economic conditionality. One month later the ECB formally adopted a policy called Outright Monetary Transactions. The move had a dramatic effect on sovereign risk spreads without the ECB having to spend a single euro in the secondary market — at least, not yet. The big questions are, how long will the signaling effect alone suffice, and will Spain and Italy formally apply for an ESM bailout program?

“Markets have yet to recognize that both Italy and Spain have already agreed to the country-specific recommendations from the European Commission that are the policy requirements of a ‘program,’ ” says analyst Bishop. “As they believe it is unnecessary to suffer the political humiliation of public visits by the men in gray, they will try very hard indeed to let the markets see that the agreed policies are being undertaken already. But debt spreads could be wobbly during this process of discovery.”

“OMT has bought some time, but it hasn’t resolved the euro’s structural flaws,” says Michael Hintze, founder, CEO and senior investment officer of London-based hedge fund CQS. “While some progress has been made here, the OMT honeymoon may be shorter than Dr. Draghi might hope for.”

More positive news came on September 12, when Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court approved the ESM, removing another potentially large hurdle for extend and pretend. The Bundesverfassungsgericht is a deliberately dignified institution. As the court read its verdict, I was struck by the medieval red robes and caps worn by president Andreas Vosskuhle and his colleagues. The court’s robes are modeled in style and color after Renaissance Italian jurists — rosso maranello, perhaps? I asked a German diplomat friend in Berlin for some political fashion guidance. “Tiefes Scharlachrot,” she said — deep red. “No Italian sports car colors in Karlsruhe, please.”

I was also struck by how little attention the traders paid to the Greece problem after the OMT announcement and the German court ruling. Part of this is Markets 101; there just wasn’t much to trade. The Greek government and Greek banks had become wards of the European state, at the end of a long lifeline from the ECB. The other notable aspect of this relative inattention was the small scale of the Greek problems, compared with the large scale of the Spanish and Italian problems.

I spent the last week of August kicking the tires in London, Brussels and Berlin, trying to get a fix on the German political calculus surrounding extend and pretend. I was told essentially the same thing in all three capitals: A Greek exit from the euro “will make it so much more expensive to extend and pretend with Spain and Italy that the Germans will just grit their teeth and pay up,” said a Frankfurt-based trader.

Bishop believes Athens may work to make it easier for the Germans to swallow this. “As the new Greek government found itself pushed halfway out of the proverbial window, it seems to have looked down to the rocks below and decided it may be worth the effort to stay inside after all,” he says. “If they genuinely make the effort, perhaps a bit of extra time may be the cheapest option for Germany.”

That could well be the lowest-cost option in both financial and political terms. “It’s difficult to see the European political establishment letting the euro zone project disintegrate,” says CQS’s Hintze. “Once you make an irrevocable system revocable, you open up a Pandora’s box.”

The punters at Intrade are more confident in the euro zone authorities than our traders. The Intrade odds that one of the periphery countries will exit the euro zone within 12 months have been all over the map but had plunged precipitously as of mid-September. The odds were just 16 percent that a country will exit the zone by the end of 2012 — one third of the perceived risk level in June 2011 and one quarter of the perceived risk level at the end of 2011.

OIL PRICING IS ALWAYS AN element of traders’ reference scenarios. But different drivers of oil prices seize their attention over time. Sometimes it’s aggregate demand, which is slumping in the U.S. because of the rise of natural gas and fuel efficiency, or sustained incremental demand from emerging markets such as China and India. Sometimes it’s supply constraints caused by low-level strife in Nigeria or high-level strife in the Persian Gulf. The risk of an Israeli or U.S. strike on the Iranian nuclear program has been hanging over oil markets for several years now.

Over the past year the reference scenarios embraced by our traders have always looked at oil and concluded that the price trend is down. In June 2011 the mean bet was 52 percent that Brent crude oil prices would be below $100 a barrel in six months time, with a standard deviation of 21. In December 2011 the bet that oil prices would exceed the $100 mark had declined to 41 percent, with a standard deviation of 18.

In the latest reference scenario, our traders focus on supply constraints. They are concerned that the fighting in Syria could spill over into the Middle East at large. They fear that chaos could expand to the point that the principals themselves are fighting. Because there are at least three regional principals with proxies at work in Syria — Iran, Saudi Arabia and Turkey — and a fourth with both big stakes and big influence, Israel, the risks of contagion are pretty high.

“The proxy war, and that is what it is already, hasn’t created these divisions between Syria’s neighbors, but it has given these divisions a venue to intensify and accelerate,” observes Shirin Narwani, researcher at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. “The Saudis are putting in lots of money at the moment, though still not as much as in Iraq. There are large shipments of arms coming in from Libya with external funding. It’s all a bit of a mess, though this has no direct effect on oil prices other than reducing Syria’s own output, which is relatively small.

“The important price effect on oil is the risk of instability spreading to Syria’s neighbors themselves, partly Lebanon but particularly Iraq,” says Narwani. “Our medium-term supply balance assumes a fair amount of incremental output from Iraq over the next five years. There were already reasons to be cautious about that, but the chaos in Syria has been a catalyst for making the outlook gloomier.”

The Assad regime has long used proxy warfare to spar with its neighbors. Syrian proxies have called the tune for much of Lebanese politics and warfare over the past two decades, and they have selectively meddled in Palestinian, Iraqi and Kurdish conflicts at the same time. “Now the unhappy citizens of Syria are experiencing the cruel effects of proxy warfare at the wrong end of an RPG and AK-47,” says a former friend from the intelligence world.

It was always unlikely that Syria’s internal chaos could be contained and the country’s ethnic divisions glued together as the Assad regime fell apart, according to Michael Doran, a noted Arabist and a former colleague of mine at Princeton and the Pentagon, now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Saban Center for Middle East Policy. “A ‘managed transition’ is the new mantra in Washington,” says Doran. “This isn’t a policy but a prayer. And it won’t be answered. Syrian state institutions are inherently sectarian, and they are crumbling before our eyes. Syria is like Humpty Dumpty. It’s made up of four or five diverse regions glued together after World War I. The country is an accident of Great Power politics; it’s hardly a cohesive nation state. Like neighboring Lebanon, it’s now dissolving into its constituent parts.”

Intrade’s punters are now betting that Assad will hang on to power through 2012, despite Doran’s dire prediction of a Syrian fragmentation. As of late September the Intrade odds were 23.9 percent that he would fall by year-end. In August the mean bet was 70 percent that Assad would be gone by December, so the Intrade bettors appear to be losing confidence in the Syrian rebels.

“If the rebels finally succeed in dislodging the regime from the main cities, the Assad regime and its Alawite constituents will retreat to the north,” predicts Doran. “And like Hezbollah in the Bekaa Valley of Lebanon, it will become another sectarian island in an expanding Iranian archipelago of influence.”

In politics, as in asset markets, six months is a long time. Even though the collective wisdom of Intrade expects Assad to hold on to power through the end of this year, the odds of him making it to June 2013 fall to 49.9 percent, and only 40 percent see him still in power at the end of 2013. The Intrade punters are long Assad for now but definitely shorting him at the longer end of the curve.

Despite Doran’s warnings, our traders are betting that Syrian contagion will not spread into a regional conflict sharp enough to kick up the supply risk premium currently priced into oil. The mean prediction was 41 percent that it would spill over, enough to move oil prices much above $100, and 59 percent that it would be sufficiently contained to have no big influence on oil prices.

Even if Syria does erupt and crimps supply, how much would that affect prices in the face of soft demand? The European economy is down slightly, the U.S. is growing very slowly, and China is decelerating. As usual, the four drivers of the traders’ reference scenarios interact with one another, and they tend to be positively correlated. Negative outcomes, such as slow growth in China and lower oil prices, reinforce one another.

I noticed a sleek blue Ferrari (azzurro monaco) parked in front of the Berkeley hotel in late August as I was making my rounds in the City, but I couldn’t spot any others. This part of London usually features any number of Ferraris with Gulf license plates, driven fast through the narrow streets of Belgravia and around Harrods by young men in dark glasses and Polo jeans. I asked the Berkeley doorman if the sudden absence of sports cars was the result of tensions in the Middle East or the high price of gasoline. After all, the Ferrari California gets only 13 miles to the gallon. He tipped his bowler hat and said: “No sir. It’s just the dodgy weather.” • •

James Shinn ( jshinn@princeton.edu ) is a lecturer at Princeton University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science, and chairman of Teneo Intelligence. After careers on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley he served as the national intelligence officer for East Asia at the Central Intelligence Agency and then as assistant secretary of Defense for Asia at the Pentagon. He serves on the advisory boards of Oxford Analytica and CQS, a London-based hedge fund. Neither he nor any of his sons drives a Ferrari.