After retiring $2 trillion in the past five years, the record flow of stock buybacks faces new resistance. In fact, skeptical voices are being heard even from firms with maximum Wall Street credentials, such as BlackRock and Goldman Sachs. These firms have joined labor unions, think tanks, academics and candidates, both left and right, in questioning the economic efficacy of share buybacks in the current environment.

The markets have dealt a blow to the practice as well. Volatile markets in August gave further pause to boards mulling buybacks. Buybacks have even surfaced as an issue in the 2016 presidential campaign, as top Democratic candidates have linked the practice to deepening income inequality and rising executive compensation.

The latest quarterly Buyback ROI Scorecard, a benchmark developed and computed for Institutional Investor by Fortuna Advisers using Capital IQ data, provides some grist for such reservations. These quarterly scorecards treat share buybacks as if they were just another use of shareholders’ assets — like a merger or a capital investment — and then rank performance over two years at Standard & Poor’s 500 companies that retire more than 4 percent of their market capitalization or spend more than $1 billion on stock repurchases.

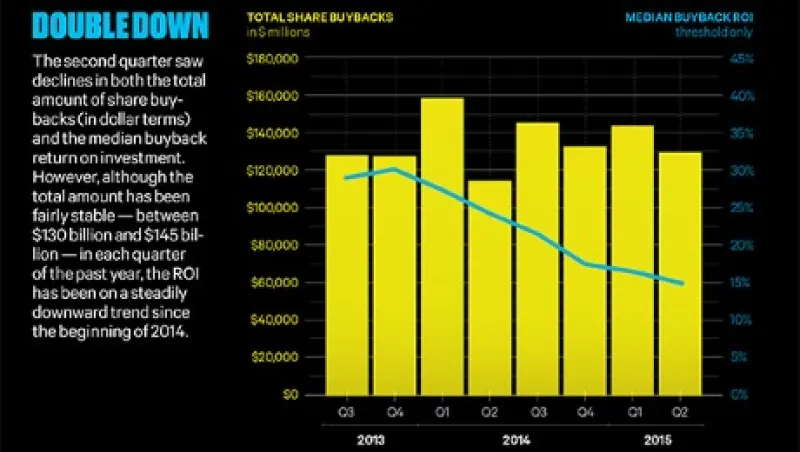

One clear trend: Companies that enjoyed robust returns on share repurchases in the bull market are suddenly seeing less bang for their buyback bucks. Median buyback return on investment (ROI) fell to 14.9 percent in the second quarter of 2015, down from 24.2 percent a year ago and 24.6 percent two years ago. An increasing number of buyback programs show losses.

Click chart to enlarge.

Each corporate buyback scorecard provides a window on buybacks over eight quarters. In case two years is not long enough to judge buyback ROI, earlier scorecards extend time frames. Combining the current scorecard with the ones published two years ago captures buyback ROI over a four-year span, from July 2011 through June 2015.

| Buyback Scorecard THE S&P 500 AS STOCK REPURCHASERS Best & Worst Companies Industry Comparisons |

A bull market, however, will never lift all boats. Pentair, an industrial company based in Manchester, U.K., fell 227 places, to No. 262 on the current scorecard. Other buyback programs remain mired in subpar performance. Sunnyvale, California–based NetApp dropped 13 places to No. 263. St. Louis–based Monsanto fell to 219 from 210.

Repurchase programs can disappoint shareholders with distressing speed. Last November, London-based fashion and luxury goods purveyor Michael Kors unveiled new buybacks. “We are pleased to initiate a share-repurchase program, which reflects the board and management’s confidence in our ability to achieve our long-term growth objectives and generate strong free cash flow,” Kors chief financial officer Joseph Parsons declared.

Eight months later Kors ROI was running at a negative 44 percent, the lowest buyback ROI of the 284 companies ranked. Parsons ignored that decline, saying, “This repurchase program underscores our commitment to returning value to shareholders, while maintaining the financial flexibility to strategically invest in our business.”

Gaps between median buyback ROI and underlying total shareholder return chiefly measure the consequence of good or bad timing. Buybacks in advance of rising prices (using average quarterly prices) generate positive buyback effectiveness as shares appreciate. Conversely, buybacks made ahead of price declines yield negative buyback effectiveness.

Inside information does not guarantee timely buybacks. In recent quarters buyback effectiveness has given ground steadily, falling to negative 3.7 percent in the latest scorecard. Two years ago, when the bull market produced buyback premiums, median effectiveness was 9.6 percent. One year ago buyback ROI matched underlying shareholder return almost exactly, meaning no premium or discount for timing decisions.

Poor timing particularly plagues cyclical industries like energy, automobiles and components. These companies often ramp up repurchases when shares are expensive and forgo them when shares are cheap. “Most companies time buybacks poorly around the up-and-down cycle,” says Fortuna CEO Greg Milano. Contrarians take note: “When trailing buyback ROI looks bad, it may signal a good time to buy back shares. If the cycle recovers, the buyback ROI could be quite attractive.”

Buybacks deliver mixed results in the latest Buyback Scorecard. Median buyback ROI over eight quarters through the second quarter of 2015 looked positive at 14.9 percent, a decent level. The trend, however, is less favorable. Declines have cut peak buyback ROI in half since the fourth quarter of 2013. In all, 142 companies lag below the median buyback ROI, and 56 buyback programs show losses.

Health care equipment and services delivered top performance across the 24 sectors through June 2015, nearly 33 percent in buyback ROI on $58 billion in buybacks. However, the sector’s two-year buyback ROI slipped by 3.7 percent. Five health care and equipment companies crowd the top ten. Louisville, Kentucky–based Humana, No. 1 in health care and services equipment and No. 2 overall in median buyback ROI, generated buyback ROI of 62.6 percent, ten basis points behind the leader, casual dining company Darden Restaurants, based in Orlando, Florida. Humana will exit the quarterly ranking on a high note. In July it accepted a $37 billion bid from Hartford, Connecticut–based insurer Aetna, 13th in buyback ROI on the current scorecard.

Click chart to enlarge.

In second and third places, technology hardware and equipment posts 28 percent in buyback ROI; food and staples retailing comes in just below 28 percent.

Still, top performance in the current ranking can’t match earlier quarters. Three companies on previous Buyback Scorecards turned in more robust buyback ROI, led by 103.5 percent buyback ROI at Dallas-based Southwest Airlines. Eight of the top ten sectors lost ground in buyback ROI. Energy companies got hammered, as one might expect given steep declines in oil prices. However, three of the bottom five performers are consumer durables and apparel businesses.

Companies are accountable for decisions that erode shareholder value. Declining buyback ROI supports arguments that money for buybacks could be better used to serve stakeholders by reinvesting in the business or hiking wages. CEOs and CFOs typically brush off these charges as naïve or misinformed.

BlackRock and Goldman Sachs pose tough questions for corporate directors who often rubber-stamp buyback authorizations at the urging of activist investors. In April, BlackRock co-founder and CEO Laurence Fink urged companies to curtail stock buybacks. Although they sometimes have a place, Fink said, he called buybacks a bad idea in the current economic climate, especially those that benefit a handful of short-term investors at the expense of long-term sustainability, a thinly veiled reference to Carl Icahn and other activists.

New York–based BlackRock, with nearly $5 trillion under management and stakes in thousands of companies, has massive clout. Companies that flout its expectations do so at the risk of riling a powerful investor. Abrupt decisions to buy back shares with cash or debt “may be good for short-term strategy,” Fink told the audience at Institutional Investor and CNBC’s Delivering Alpha conference in July, “but it could be perilous for the long-term viability of the company. We will be hostile to things like that.”

Fink rejects the rationale that buybacks make sense because companies lack opportunities to reinvest. Good leadership and innovation produce opportunities, he says. If, instead, companies elect to retire stock at a record pace, he sees wider consequences. Besides weakening some companies, Fink warned, buybacks “could be one of the reasons why we have a below-trend-line economy. We’re not investing for the future as much as we should.”

A team of Goldman Sachs analysts led by David Kostin drew a similar conclusion in June. Goldman’s review of buybacks since 1999 revealed a peak at the start of the financial crisis, when companies deployed a third of their cash to repurchase shares. Combine that with lofty price-earnings ratios, and buybacks in this climate invite disappointing returns. “Tactically, repurchases may lift share prices in the near term,” the Goldman analysts reported, “but in our view it is a questionable use of cash at the current time, when the P/E multiple of the market is so high.”

Goldman’s advice on stock buybacks was to just say no. Companies should buy other companies, not their own stock, when P/E multiples are so high, the firm advised, no doubt also aware that M&A generates more fees for Wall Street than buybacks.

Meanwhile, long-standing buyback critics have amped up their attacks, which grew after the September 2014 Harvard Business Review article “Profits Without Prosperity” by University of Massachusetts professor William Lazonick (see “U.S. Buybacks Rebound but Face Sharp Criticism,” Institutional Investor, January 2015). The article garnered coverage in major media, spurring headlines like “Owner Take All” in the Washington Post.

The culprit in the buyback phenomenon is Rule 10b-18, Lazonick charges, which frees companies to repurchase shares with few restraints — even if consequences trigger higher executive compensation. When created in 1982 this so-called safe harbor unleashed a flood of buybacks that has grown significantly. Lazonick does not mince words. “In my view,” he charges, “Rule 10b-18 legalizes stock market manipulation.”

Citing potential stock manipulation, Senator Tammy Baldwin, a Democrat from Wisconsin, told Institutional Investor, “Congress and the SEC must take a serious look at stock buybacks.” In a letter to Securities and Exchange Commission chair Mary Jo White, Baldwin requested a list of investigations into possible violations of Rule 10b-18. White emphasized a history of SEC actions where price manipulation is suspected but added that it doesn’t extend to buybacks. “Because Rule 10b-18 is a voluntary safe harbor, issuers cannot violate this rule,” White replied.

Wider visibility makes buybacks a bigger target, especially in the context of executive compensation that seems to exacerbate income inequality. The issue surfaces these days in labor disputes. A turnaround plan at struggling Oak Brook, Illinois–based fast-food giant McDonald’s that features upward of $8 billion in stock buybacks has left franchisees who want capex unhappy. Workers at General Electric see injustice when they get pink slips and wage cuts while the company earmarks billions of dollars to buy back shares.

Echoing populist objections, Senator Elizabeth Warren, a Democrat from Massachusetts, has pressed the SEC to probe rules that govern buybacks that could undermine the economy, the Boston Globe reported. She drew attention to layoffs at Cisco Systems while the San Jose, California, networking giant was spending billions of dollars on buybacks.

Research published in June 2015 by the online Academic-Industry Research Network, with backing from the Service Employees International Union, singled out buybacks in the fast-food industry as a bad idea on several levels. “We argue that the company’s recent ‘turnaround plan’ all but sacrifices the interests of both its workers and its franchisees, notwithstanding an historical commitment to them as stakeholders in the McDonald’s ‘system,’ to the interests of speculative shareholders,” authors Lazonick, Matt Hopkins and Ken Jacobson wrote.

Other voices on the left concur. “Finance used to be about putting money into firms. Now it’s about getting money out of firms, where buybacks are one of the most important tools,” says fellow Mike Konczal at the New York–based progressive think tank the Roosevelt Institute. Buybacks reveal lasting damage to the economy, adds Josh Bivens, research and policy director at the Economic Policy Institute, an arm of the Brookings Institution. Managers lack confidence in demand that would warrant investment in property, plant, equipment and skilled workers to operate them. So they buy back shares. “It’s another sign of dysfunction,” Bivens says.

Democratic candidates have responded to the antibuyback sentiment. “Last year the [buyback] total reached a record $900 billion,” Hillary Clinton told an audience at New York University’s Stern School of Business. “That doesn’t leave much money to build a new factory, or a research lab, or to train workers or to give them a raise.” Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who is challenging Clinton for the Democratic nomination, has echoed similar concerns.

Surging buybacks also spur questions in conservative circles. “It’s not a problem but rather the symptom of a problem,” says Mark Calabria, director of financial regulation studies at the libertarian Washington-based Cato Institute. As he sees it, buybacks expose flawed judgments by the Federal Reserve. “They are a rational response to our current monetary policy that has made debt look so much cheaper than equity,” Calabria says. On a risk-adjusted basis, low interest rates tend to stifle the case for reinvestment, nudging companies to repurchase their stock instead.

Buybacks also shine a light on questionable judgment in C-suites, adds Alex Pollock, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative Washington think tank. Even armed with inside information, managers seldom demonstrate an edge over anyone else when judging shares as cheap or expensive. A case in point is the stock buybacks preceding the financial crisis. “They were taking capital out just when they needed it,” says Pollock.

Beware unintended consequences of reining in share buybacks, warns assistant professor of finance Alice Bonaimé at the University of Arizona. “Disassociating executive compensation from performance measures affected by buybacks, such as earnings per share, sounds like an easy solution,” says Bonaimé, whose paper on mandatory buyback disclosure and firm behavior will be published in the Accounting Review. Steps that disconnect executive pay from buybacks might reduce stock manipulation. But if they weaken alignment with managers, investors might pay a much bigger price.