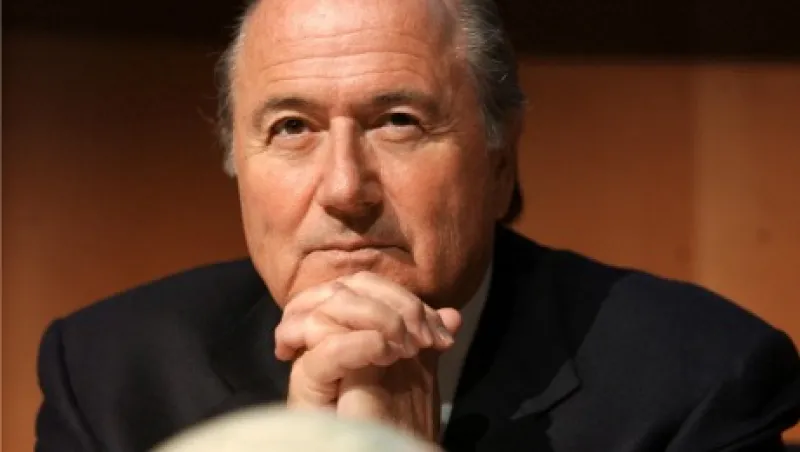

Standing in front of a phalanx of flag-carrying youths representing the 209 members of FIFA on Thursday at the opening of the annual congress of world soccer’s governing body, Sepp Blatter seemed oddly diminished. The impression was born not just of the physical contrast between this frail, hunched 79-year-old and the congress’s dazzlingly tall host, a blonde woman of indistinct northern European heritage charged with the task of sticking to a dissonantly upbeat script. As FIFA reeled this week from a series of unprecedented corruption allegations by law enforcement officials in the U.S. and Switzerland, Blatter — long a figure of ridicule among the global soccer intelligentsia but transformed overnight into a target of almost universal outrage — seemed to be fighting for his political life.

“We — or I — cannot monitor everyone all of the time,” Blatter told those assembled in Zurich, absolving himself of blame for the actions of the 14 people, nine of them senior FIFA officials, indicted by the U.S. Department of Justice on corruption charges early on Wednesday. It was important for FIFA and the “football family” to stand united and take action against the miscreants dragging the world’s most popular sport “through the mud,” Blatter added. “The next few months will not be easy for FIFA. I am sure more bad news will follow.”

Blatter’s words were intended to shore up his authority ahead of today’s presidential election, in which the Swiss career sports administrator will seek a fifth term at the helm of FIFA. Instead, the performance took its place in the first rank of history’s great demonstrations of the dark art of political bluffing and blame-shifting — right up there with Richard Nixon in the final months of his presidency, or Bill Clinton telling us he did not have sexual relations “with that woman.” Today’s vote is expected to be a close-run thing: Blatter is counting on support from his traditional strongholds in the developing world — Africa and Asia especially — even as his challenger, Prince Ali bin al-Hussein of Jordan, seeks to gain support from Europe and the Americas in the wake of the widespread disgust that Wednesday’s swoop by U.S. and Swiss authorities has triggered. But Blatter is firmly in the sights of law enforcement officials, according to those close to the matter — and will remain so no matter what the result of today’s poll.

“They want to get to the one guy at the top of the food chain,” says John Coffee Jr., a law professor at Columbia University with a deep knowledge of the history of U.S. prosecution of extraterritorial criminal cases. “It’s clear that they care about the future of soccer and want to do something about it.”

Many have argued that Wednesday’s arrests and the legal actions that will follow, despite their shock value, will likely do little to disturb FIFA’s underlying governance structures, which are famously opaque. World soccer is run, essentially, by FIFA’s 24-member executive committee, a cabal of veteran administrators with no accountability or external oversight and, if history is any guide, little appetite for internal structural reform. But what makes this case so fascinating is the degree of the Justice Department’s apparent long-term commitment to the cause of eradicating corruption in FIFA. New Attorney General Loretta Lynch, who oversaw much of the grunt work for Wednesday’s arrests during her previous job as U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York, has stated that this first round of indictments represents the beginning, not the end, of U.S. involvement in the issue. No other country apart from the U.S. has a body of law with the extraterritorial reach to put together a case indicting suspects across three continents and bringing them together in a single trial, as the justice department did here.

But there’s evidence to suggest that the action against FIFA’s malefactors is more than a routine application of extraterritorial jurisdiction, which U.S. authorities regularly draw on in their prosecution of criminal matters. The moral decay of world soccer’s ruling body has become something of a pet cause for the U.S. enforcement community. In 2012 FIFA enlisted Michael Garcia, a former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, to lead an independent investigation into its ethics committee and corruption in world football more generally. Garcia completed the report 18 months later, and FIFA promptly refused to make it public, releasing a summary of the report instead. Garcia swiftly denounced the summary as incomplete and inaccurate, saying that it misrepresented the scale of graft throughout FIFA’s upper echelons. FIFA brushed aside the complaint, as well as a formal appeal by Garcia against the summary of his report. The farce ended with Garcia, a lion of U.S. law enforcement whose pre-FIFA resume included the federal investigation against former New York governor Eliot Spitzer and numerous high-profile terrorism cases, resigning in late 2014 and heading for the footballing hills, chastened and humiliated. This is how FIFA operates: with none of the transparency of open court proceedings and all the secrecy of a star chamber.

In this case U.S. law enforcement officials are hoping that the simple moral economics of plea bargaining will lead them up the chain of command and allow them to nab Blatter and his closest associates. “Most of these people are in their 60s,” Coffee says of the 14 arrested on Wednesday. “They do not want to face living their last years in an American prison. They have incredible incentives to see if they can plea bargain.” More lenient sentences for those arrested could yield nuggets of information big enough to go after Blatter. That, at least, is the idea.

But as the claims drag on, it’s possible U.S. officials will face a backlash from those decrying American interference in “the world game.” Russian President Vladimir Putin, whose country was controversially awarded the right to host the 2018 World Cup, has already decried Wednesday’s actions as an example of U.S. imperialism. Putin hardly speaks as the moral conscience of the world, but there’s little doubt that defense attorneys for those arrested in Zurich will draw on similar arguments in their attempts to resist extradition of their clients to face trial in the U.S. On Wednesday the Justice Department’s actions and public statements had a ringing moral clarity to them. However, patience for the broader push against corruption in soccer may fray with time, especially if U.S. actions begin to have a negative impact on the game itself or impede the efficient staging of major international tournaments.

“It’s a little like the American armed intervention in Afghanistan,” says Stefan Szymanski, a professor of sport and business at the University of Michigan. “On day one everything looks clear and you’re on the side of the angels, but after a while you get bogged down and lose international support.”

This isn’t the first time FIFA has felt the force of external outrage. In 2010, former FIFA secretary general Michel Zen-Ruffinen went public with sensational allegations that members of the executive committee had taken bribes. In response, nothing happened. In 2011, in a chaotic and spiteful presidential election, Blatter and his rival candidates flung accusations of corruption at each other. In the end, executive committee members Jack Warner and Mohamed Bin Hammam were expelled from FIFA; Blatter won the presidency and dodged further allegations of impropriety; and nothing further happened. In 2014, Garcia released his report; FIFA suppressed it; again, nothing happened.

Will this time be any different? U.S. authorities surely hope so. But it’s not clear where exactly the balance between optimism and naivety in that hope lies. History suggests that in the collision between U.S. justice — despite its uniquely global reach and the marshal clarity of its moral code — and the Byzantine obfuscations of FIFA’s governance structure, dark is more likely to prevail over light.