As investors dive deeper into companies’ capital structures in search of yield, they’re flocking to perpetual bonds. Also known as hybrid bonds, perpetual bonds have no fixed maturity date and get treated as equity rather than debt. These instruments, which carry more risk than a company’s usual senior debt, are popular because they can return 4 to 5 percent in today’s near-zero interest rate conditions.

“The low-yield environment and investors’ current high tolerance for corporate credit risk have combined to create conditions where borrowers can access the market at very attractive yields relative to their senior debt,” says Bryan Pascoe, London-based global head of debt capital markets at HSBC Holdings. “The jumbo deals we have seen this year mark the arrival of a new asset class for 2013.”

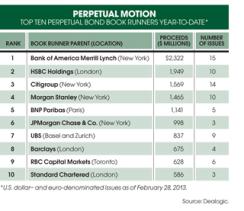

Perpetual bonds are seeing their highest-ever level of issuance. Through March 14, $28.9 billion worth had hit the global market in 2013, according to Dealogic. A record start to the year, this total surpasses the combined volume for the same period for all three previous years.

Issued in U.S. dollars, euros and pounds sterling, perpetual bonds are redeemable within five to 13 years. Borrowers usually redeem, and deals are structured to encourage that. Since perpetual bonds emerged in the mid-1990s, banks and insurance companies have been prolific issuers, especially in Europe, where they want to boost capital buffers to meet Basel III requirements. Perpetuals are attractive because they offer a way to raise capital at a time of low stock prices without diluting shareholder equity.

“We have seen booming demand from investors for hybrid bonds,” says Kapil Damani, a London-based senior structurer with French bank BNP Paribas, a global book runner on the EDF blockbuster along with Citigroup and HSBC. “New investors are also coming into the asset class, such as high-yield [funds], private banking clients and hedge funds, as well as traditional institutional investors.”

In Europe local insurers are avid buyers of perpetual bonds; deals are luring wealthy Asians and U.S. retail investors too, Damani says. Other European corporate issuers this year include Dutch telecommunications conglomerate Koninklijke KPN, Telekom Austria and French environmental services company Veolia Environnement.

The U.S. market for perpetual offerings is geared more toward retail investors; deals usually fall below $500 million, though last year General Electric Co. unit GE Capital set a precedent with a $2.25 billion issue. Also, while perpetual bonds are tax-deductible in Europe, tax treatment is less favorable for U.S. companies. In the U.S. such bonds take the form of trust-preferred securities, but these don’t count as equity under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. As a result, foreign companies can tap U.S. demand that domestic borrowers fail to meet.

Treasurers usually deploy perpetual bonds for specific corporate finance purposes. In 2006 there was a glut of issuance related to acquisition financings. And last month KPN, part-owned by Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim’s América Móvil telecom group, sold $2.6 billion of perpetual bonds in three currencies as part of a rights issue that also sought to bolster the company’s balance sheet. In February, KPN said it was raising €4 billion in equity capital, comprising a €3 billion stock offering and hybrid bonds. Using perpetuals to plug the gap prevented the dilution of Móvil’s stake.

The EDF deal suggests that perpetual bonds could become a fixture of the corporate capital structure. “For most companies hybrid bonds result in a lower weighted average cost of capital compared with traditional financing instruments,” BNP Paribas’s Damani says. “And as tax-deductible equity, they are a CFO’s dream.”