Earlier this week I wrote about the psychological challenges that Apple shareholders face. I also discussed the evolution of Apple’s “i” gadgets — the iPod, iPhone and iPad — and how they have created an ecosystem unlike those of other technology companies.

Apple’s ecosystem is an important and durable competitive advantage; it creates a tangible switching cost (or, an inconvenience) after Apple has locked you into the i-ecosystem. It takes time to build an ecosystem that consists of speakers and accessories that will connect only via Apple systems: Apple TV, which easily recreates an iPhone or iPad screen on a TV set; the music collection on iTunes (competition from Spotify and Google Play lessens this advantage); a multitude of great apps (in all honesty, gaming apps have a half-life of only a few weeks, but productivity apps and my $60 TomTom GPS have a much longer half-life); and, last, the underrated Photo Stream, a feature in iOS 6 that allows you to share photos with your close friends and relatives with incredible ease. My family and friends share pictures from our daily lives (kids growing up, ski trips, get-togethers), but that, of course, only works when we’re all on Apple products. (This is why Facebook bought Instagram for $1 billion. Photo Stream is a real competitive threat to Facebook, especially if you want to share pictures with a limited group of close friends.)

The i-ecosystem makes switching from the iPhone to a competitor’s device an unpleasant undertaking, something you won’t do unless you are really significantly dissatisfied with your i-device (or you are simply very bored). How much extra are you willing to pay for your Apple goodies? Brand is more than just prestige; it is the amalgamation of intangible things like perceptions and tangible things like getting incredible phone and e-mail customer service (I’ve been blown away by how great it is!) or having your problems resolved by a genius at the Apple store.

Of course, as the phone and tablet categories mature, Apple’s hardware premium will deflate and its margins will decline. The only question is, by how much? Let me try to answer that.

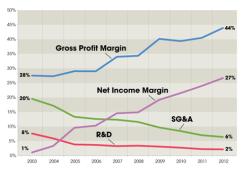

From 2003 to 2012, Apple’s net margins rose from 1.1 percent to 25 percent. In 2003 they were too low; today they are too high. Let’s look at why the margins went up. Gross margins increased from 27.5 percent to 44 percent: Apple is making 16.5 cents more for every dollar of product sold today than it did in 2001. Looking back at Nokia Corp. in its heyday, in 2003 the Finnish cell phone maker was able to command a 41.5 percent margin, which has gradually drifted down to 28 percent. Today, Nokia is Microsoft’s bitch, completely dependent on the success of the Windows operating system, which is far from certain. Nokia is a sorry shell of what used to be a great company, while Apple, despite its universal hatred by growth managers, is still, well, Apple. Its gross margins will decline, but they won’t approach those of 2003 or Nokia’s current level.

For Apple to conquer emerging markets and keep what it has already won there, it will need to lower prices. The company is not doing horribly in China — its sales are running at $25 billion a year and were up 67 percent in the past quarter. However, a significant number of the iPhones sold in China (Apple doesn’t disclose the figure) are not $650 iPhone 5’s but the cheaper 4 and 4s models. (Also, on a recent conference call, Verizon Communications mentioned that half of the iPhones it has sold were the 4 and 4s models.) Apple’s price premium over its Android brethren is not as high as everyone thinks.

What is truly astonishing is that Apple’s spending on R&D and selling, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses has fallen from 7.6 percent and 19.5 percent, respectively, in 2003 to a meager 2.2 percent and 6.4 percent today. R&D and SG&A expenses actually increased almost eightfold, but they didn’t grow nearly as fast as sales. Apple spends $3.4 billion on R&D today, compared with $471 million in 2001. This is operational leverage at its best. As long as Apple can grow sales, and R&D and SG&A increase at the same rate as sales or slower, Apple should keep its 18.5 percentage points gain in net margins through operational leverage.

Growth of sales is an assumption in itself. Apple’s annual sales are approaching $180 billion, and it is only a question of when they will run into the wall of large numbers. At this point, 20 percent-a-year growth means Apple has to sell as many i-thingies as it sold last year plus an additional $36 billion worth. Of course, this argument could have been made $100 billion ago, and the company did report 18 percent revenue growth for the past quarter, but Apple is in the last few innings of this high-growth game; otherwise its sales will exceed the GDP of some large European countries.

If you treat Apple as a pure hardware company, you’ll miss a very important element of its business model: recurrence of revenues through planned obsolescence. Apple releases a new device and a new operating system version every year. Its operating system only supports the past three or four generations of devices and limits functionality on some older devices. If you own an iPhone 3G, iOS 6 will not run on it, and thus a lot of apps will not work on it, so you will most likely be buying a new iPhone soon. In addition — and not unlike in the PC world — newer software usually requires more powerful hardware; the new software just doesn’t run fast enough on old phones. My son got a hand-me-down iPhone 3G but gave it to his cousin a few days later — it could barely run the new software.

As I wrote in my previous column, Apple’s success over the past decade is a black swan, an improbable but significant event, thanks in large part to the genius of Steve Jobs. Today investors are worried because Jobs is not there to create another revolutionary product, and they are right to be concerned. Jobs was more important to Apple’s success than Warren Buffett is to Berkshire Hathaway’s today. (Berkshire doesn’t need to innovate; it is a collection of dozens of autonomous companies run by competent managers.) Apple will be dead without continued innovation.

Jobs was the ultimate benevolent dictator, and he was the definition of a micro-manager. In his book Steve Jobs, Walter Isaacson describes how Jobs picked shades of white for Apple Store bathroom tiles and worked on the design of the iPhone box. He had to sign off on every product Apple made, down to and including the iPhone charger. His employees feared, loved and worshiped him, and they followed him into the fire. Jobs could change the direction of the company on a dime — that was what it took to deliver black i-swans. Jobs is gone, so the probability of another product achieving the success of the iPhone or iPad has declined exponentially.

What is really amazing about Apple is how underwhelming its valuation is today — it doesn’t require new black swans. In an analysis we tried very hard to kill the company. We tanked its gross margins to a Nokia-like 28 percent and still got $30 of earnings per share (the Street’s estimate for 2013 is $45), which puts its valuation, excluding $145 a share in cash, at 10 times earnings. We killed its sales growth to 2 percent a year for ten years, discounted its cash flows and still got a $500 stock.

There is a lot of value in Apple’s enormous ability to generate cash. The company is sitting on an ever-growing pile of it — $137 billion, about one third of its market cap. Over the past 12 months, despite spending $10 billion on capital expenditures, Apple still generated $46 billion of free cash flows. If it continues to generate free cash flows at a similar rate (I am assuming no growth), by the end of 2015 it will have stockpiled $300 of cash per share. At today’s price it will be commanding a price-earnings ratio (if you exclude cash) of 4.

Of course, the market is not giving Apple credit for its cash, but I think the market is wrong. Unlike Microsoft, which does something dumber than dumb with its cash every other year, Apple has a pristine capital allocation track record. It has not made any foolish acquisitions — or, indeed, any acquisitions of size. Other than buying an Eastern European country and renaming it i-Country, Apple will not be able to acquire a technologically related company of size, nor will it want or need to. The cash it accumulates will end up in shareholders’ hands, either through dividends or share buybacks.

What is Apple worth? After the financial acrobatics I’ve done trying to murder the valuation of Apple, it is easier to say that it is worth more than $450 than to pinpoint a price target. When I use a significantly decelerating sales growth rate and normalize margins (reducing them, but not as low as Nokia’s current margins), I get a price of about $600 to $800 a share.

Growth managers don’t want Apple to pay a large dividend, as though that would somehow transform this growing teenager into a mature adult. But I have news for them: Apple already is a mature adult. Second, when your return on capital is pushing infinity (as Apple’s is), you don’t need to retain much cash to grow. Two thirds of Apple’s cash is offshore, but that doesn’t make it worthless; it just makes it worth less — only $65 billion, maybe, not $97 billion, once the company pays its tax bill to Uncle Sam.

In the short term none of the things I am writing about here will matter. Remember, “Everyone knows Apple is going to $300,” as a client recently e-mailed me, as everyone knew it was going to a $1,000 a few months ago when Apple’s stock was trading at $700. The company’s stock will trade on emotion, fundamentals will not matter, and growth managers will likely rotate out of Apple, because once the stock declined from $700 to $450, the label on it changed from “growth” to “value.” But ultimately, fundamentals will prevail. Like the laws of physics, they can only be suspended for so long.

Vitaliy Katsenelson (vk@imausa.com) is CIO at Investment Management Associates in Denver and author of The Little Book of Sideways Markets.