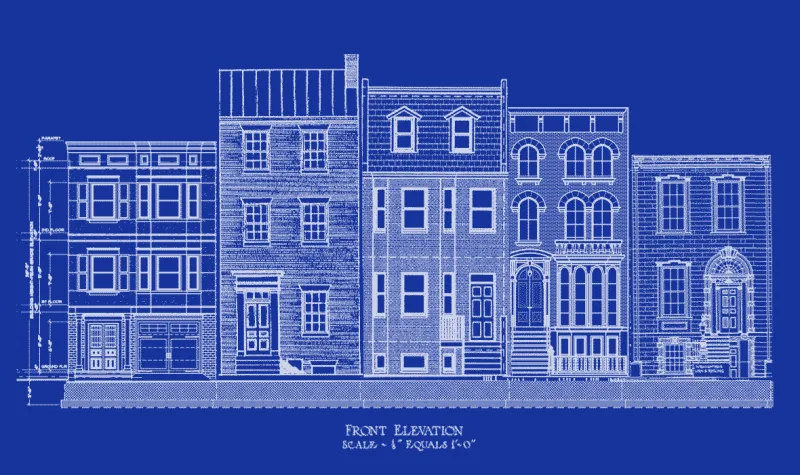

Illustrations by Doug Chayka

Walking down the cobblestone streets of the West Village in New York City, for a minute you can be transported in time. You pass magnificent 18th and 19th century brownstones on winding streets like West Fourth Street, where residential homes mingle with hip, trendy eateries, and the mood turns almost serene. This city of 8.6 million inhabitants slows down in this oasis, feeling less frenetic, and it’s no wonder why so many glitterati want to live here.

The rich and famous flock to the West Village. Actors Matthew Broderick, Sarah Jessica Parker, James Spader, and Glenn Close, author Malcolm Gladwell, and late-night talk-show host Seth Meyers all reside here.

It’s also the neighborhood where urbanist Jane Jacobs lived, which she portrayed in her seminal book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. She described “the intricate sidewalk ballet” on the narrow, serpentine streets of the West Village, where neighbors bump into and watch out for each other. It’s one of the only places in New York where you can truly get lost.

But all is not peaceful in paradise.

A bevy of hedge fund managers and private equity titans are choosing to leave suburbia to construct their mega-mansions in the West Village and other premier Manhattan environs. If hedge fund owners have made billions — imagine Bobby Axelrod (Damian Lewis), the fictionalized hero of the Showtime series Billions — there’s no better way to demonstrate their wealth and achievement than building a massive home in Manhattan. But neighbors who have welcomed rock stars and CEOs are balking at their new, not-very-neighborly hedge fund neighbors.

A prime example arose recently when Steven Cohen opted to erect a house in New York. In 2012 the billionaire founder of SAC Capital Advisors and, now, Point72 Asset Management reportedly paid $38.8 million for 145 Perry Street in the West Village. This block isn’t filled with quaint brownstones, but instead has one of the few remaining parking garages in the area, Cooper Classic Cars, a high-end auto repair shop, and some weathered, six-story walk-up apartments.

Cohen’s house will stand out on the corner property as the only new five-story domicile on the quiet block, which is off the beaten track, away from bustling Hudson Street.

Cohen himself has faced considerable controversy. Prosecutors with the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, in conjunction with the FBI and the Securities and Exchange Commission, investigated SAC Capital for insider trading. The firm pleaded guilty, paid a massive fine, and shut down over the case, but Cohen was never personally charged. However, he agreed to stop investing outsiders’ funds for a time to settle with federal authorities.

When Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, studied the proposal for Cohen’s new edifice, he was appalled. “It looked more like a moat. It fit more for Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills or Miami. It has a glitzy, fortress-like aesthetic. It doesn’t match the character of the neighborhood,” he says. (Berman’s organization oversees both the West Village and the East Village, which together make up Greenwich Village.)

Although the house will be five stories tall when completed, it wasn’t the size that distressed Berman. Several buildings on the block match that height. Nor was Berman swayed by Cohen’s tattered reputation. “We never oppose a project based on who’s behind it, but we work to maintain the historical charm and look of the neighborhood. That’s why most people are drawn to it and want to build these big, wonderful homes,” he explains.

Cohen bought the property knowing it was located in a landmarked neighborhood, Berman points out. “Our sole objection was on the design perspective and how it would affect a special and unique charm that it is benefiting from,” he says.

Indeed, many West Village residents are enamored of its historic and landmarked status. “We have many active supporters of preservation, who do a great job — whether hedge fund investors or other people — with huge amounts of resources,” Berman points out.

But Cohen’s proposed home “shows a degree of hubris and lack of commitment to the social contract of what makes this neighborhood so desirable. Each person has to do their part to maintain its character, and it’s something that everyone benefits from. As far as we’re concerned, everyone’s welcome in this neighborhood, but managing the character of the neighborhood is important to everyone who lives here,” Berman says.

Cohen’s spokesperson declined to comment for this article.

But the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) “evaluates the height, the scale, the massing, the material, and the general composition of new buildings within the context of a particular area,” an LPC spokesperson says. “Does it have a relationship with the historic and architectural character of that particular district?” It determined that the new townhouse “will be in keeping with the scale of historic apartment buildings outside the historic district on the west side of Washington Street.”

Cohen’s new light-colored brick townhouse would be richly appointed with bronze-framed casement windows, a recessed atrium in terracotta tiles, bronze-and-glass doors, a rear garden, and two chimney flues.

When the LPC authorized the building at 145 Perry Street, it concluded that “the corner townhouse would be harmonious to the Washington and Perry streetscapes that are characterized by a mix of commercial lofts, as well as row house and apartment buildings.”

Berman blames the LPC for diluting its standards and not defending the sanctity of the neighborhood’s architecture. It “has become more accepting of out-of-character intrusions in historic districts like this one,” he says.

The local community board opposed the project, unsuccessfully. Berman’s has resigned to “wait and see” what effect the modern mansion has on the West Village landscape. He may need to get used to these scenarios.

Hedge fund managers can afford to build urban chateaus in Manhattan’s historic neighborhoods, which are among the world’s most expensive. According to Institutional Investor’s Rich List, four hedge fund managers personally earned more than $1 billion each in 2017 and the top 25 netted a combined $15.4 billion.

Hedge funds and their employees have traditionally opted for suburban home bases, repelled by New York City’s high taxes. But Connecticut is no longer the tax bargain it once was, and falling home prices in Greenwich attest to financiers’ flight from the state. Some have gone far south, including Tudor Investment Corp.’s Paul Tudor Jones, who bought a $71 million Palm Beach, Florida, estate in 2015, and now reportedly plans to make $6 million in renovations.

Many, if not most, of the New York mansions owned by hedge fund moguls are not their official domiciles, but rather billionaire pieds-à-terre. Cohen, for example, owns two East Hampton estates in addition to the Perry Street property, and remains a resident of Greenwich, Connecticut.

He did his future community a courtesy by identifying himself as the buyer behind 145 Perry Street. Others do not. In April, The Wall Street Journal reported that the wife of Israel Englander — London-based founder of Millennium Management — used a trust to buy a $60 million Park Avenue apartment. It’s often impossible to ascertain who exactly is developing a certain property or building a mega-mansion, explains Sean Khorsandi, executive director of Landmark West, a nonprofit dedicated to preservation on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Most of the properties are owned by limited liability companies, or LLCs, which obscure the actual owner. “Rooting that out isn’t our business,” Khorsandi acknowledges.

He says the Upper West Side is the country’s second-densest neighborhood, after the Upper East Side, but is fast losing residents. “We’re becoming less dense. There are fewer people living here than there were in the last census,” he says. And what’s driving that trend is more LLCs — owned by an assortment of Wall Street financiers and entrepreneurs — acquiring row houses and turning them into private residences.

As long as the LLC is developing the house for a family, “you can push the neighbors out, who have held the neighborhood together for years,” Khorsandi says. “Fewer people are living in more space, and they still want to expand the house.” Most often, renovation plans include a “rooftop addition, a rear-yard extension, and a lowering of the sub-cellar, often for wine storage or a home gym,” he says. One consequence is “fewer people shopping at Zabar’s” — an iconic Jewish deli — “and less commercial traffic. There’s a loss of fabric and character.”

Some Wall Streeters keep extending their homes to meet their personal needs. For example, Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich, the primary owner of the private investment company Millhouse, gained approval from the LPC to turn three townhouses on East 75th Street into one. Then he acquired a fourth brownstone, reconfigured the plans in 2017, and again got the go-ahead from the LPC, which decided that the new plans were “very respectful for the district overall.” Those townhouses contained 18 apartments before Abramovich renovated.

And that helps explain why experts like Lynn Ellsworth, president of New Yorkers for a Human-Scale City, a nonprofit, objects to these mega-mansions. “We want these historic districts to be vibrant, full of street life, so you get the full urban experience,” she says. Historic districts need to be accessible to a variety of economic classes, not “just the gentry,” Ellsworth says. “If we turn them into empty palaces, that’s the worst way to handle the urban dilemma we’re faced with in Manhattan right now,” she adds, alluding to the city’s affordable housing crisis. “The law must be changed so it is clear who actually owns the property,” she says. “It’s how a democratic society should operate.” Such a change to the laws would also prevent money laundering.

What’s at the root of investors’ desire to buy landmarked properties, often in secret, and build these mega-mansions? And at what cost to the sector’s reputation?

If the industry is grappling with these issues, it’s not at all apparent.

The Hedge Fund Association — the industry's not-for-profit trade and lobbying organization dedicated to “advancing transparency, development, and trust in alternative investments” — declined to answer questions directly and instead issued a statement.

“The biggest factor I think is time, and time is money,” vice president Tony Acquadro said in the statement. “By avoiding two hours of commuting between Greenwich and New York City, you can allocate those two hours to increasing productivity.” Hence, a hedger funder’s moving in proximity to the trading floor enables him to “process information and act quickly in order to avoid a capital loss. Many traders look at the markets around the clock. It’s not a 9-to-5 job; it’s a 24-hour job,” Acquadro said.

Leo Braudy, who wrote The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History, an investigation into why people crave notoriety, says constructing these large homes springs from “a question of recognition. Rather than the desire to do something, it’s a desire to be something, to be recognized.”

For hedge fund owners, “it’s the ego being acknowledged socially,” Braudy says. With hedge funders, the stock market’s constant fluctuations yield a mercurial quality to their lives, but these homes are constructed of bricks and concrete, are stable, and can last a lifetime. The homes serve a dual purpose, he suggests: They demonstrate to people that the owners have made it and certify self-achievement. Building in the West Village or Upper West Side conveys status. “To be recognized, you have to be on a recognizable stage,” Braudy says.

Even if some neighbors balk at the prospect of a super-sized home, most hedge funders aren’t deterred by negative publicity. “For some people, infamy is as good as fame. It’s still recognition. Everyone notices him,” Braudy explains.

But Braudy says such conspicuous consumption casts a pall on the financial industry. Hedge funders are supposed to make money for their investors, not primarily line their own pockets. Years of relatively weak performance from many managers makes the optics even worse, for the individuals but also the industry as a whole. “If you’re not doing so well, why call attention to your profligate spending?” he wonders.

Mary Gresham, an Atlanta-based clinical psychologist who has treated and studied the ultra-rich, suggests looking from the viewpoint of the hedge funder at issues these mansions raise. People who acquire gobs of wealth, in contrast with those born into it, confront a whole bevy of problems fitting in, maintaining the values they were born with, and being accepted for who they are, not what they could do for others.

“Sudden money syndrome” frequently strikes the self-made rich, she says. They often don’t know how to handle their new-found wealth and aren’t sensitive about antagonizing others. Most times, Gresham says, the ultra-rich “buy into a neighborhood and try to join a social group that reflects their new wealth.” Yet ironically, most wind up “more isolated” in urban environs than in suburban enclaves, despite the latters’ multi-acre estates and privacy. The mega-rich must contend with issues of “personal safety, to avoid being robbed or tricked or manipulated” and often seek the mega-mansion as a refuge from being exploited by others.

Hedge funders who opt to live in the West Village and other urban neighborhoods are seeking a “walking neighborhood, with accessibility to neighbors and regular people,” Gresham says. “They’re tired of being isolated. It goes against our human nature. They seek a variety of people as opposed to only one kind. Most wealthy enclaves are very isolated and homogeneous.”

And yet she suggests that many ultra-rich tend to be tone deaf, pursue what they want, and fail to consider whether their mega-mansion blends into the environs. The entrenched neighbors may feel the mega-mansion “doesn’t belong. And there’s a lack of awareness on the part of the wealthy person on how he is impacting the people around him,” she says. Often the ultra-rich have “no empathy of the neighborhood, no feeling how their neighbors feel invaded if something that doesn’t belong there is now next door to them,” she says.

The top earners can become “self-absorbed” from being catered to by subordinates and most others who want something from them, Gresham says. “They begin to lose their deeper connection with people that is more emotional.”

Nonetheless, she says, the ultra-rich are consumed with one nagging question that vexes them: How does their intensifying wealth affect their children? In therapy, Gresham asks hedge funders looking to build an urban mansion, “Is there any way you could meet your needs without alienating the people around you? How can you integrate what they need with what you need so your children won’t be seen as outsiders?” Those questions often strike a deep chord and lead to their making some adjustments. She might ask, “Could you buy three adjoining townhouses and cluster them together, rather than develop a mega-mansion that sticks out like an interloper?”

Indeed, the married couple Sarah Jessica Parker and Matthew Broderick acquired two townhouses on West 11th Street for a reported $34.5 million and combined them into a 13,900-square-foot mega-mansion without causing a stir. Facebook’s first president and Napster co-founder Sean Parker added two five-story townhouses on West 10th Street to the adjacent townhouse he already owned.

The worst thing that can happen to hedge funders moving into a new neighborhood is to be “resented and despised in the community,” Gresham says. “What’s worse than being an outcast?” To avoid such a fate, she urges the ultra-rich to accentuate the positive rather than be disruptive. “Money is a great resource, and perhaps they could build a new community center or develop a new resource that the neighborhood needs.”

Indeed, any visitor to the venerable New York Public Library on 42nd Street will likely feel some gratitude to Stephen Schwarzman, CEO of the Blackstone Group and a trustee of the library. His staggering $100 million gift to the library helped renovate and upgrade it, prompting Anthony Marx, the library system’s president, to describe him as “the second-most important donor in the library’s history, after Andrew Carnegie.”

But the public-facing role of community benefactor may be a more natural fit for public CEOs like Schwarzman than for hedge fund managers. These two brands of business titan tend to operate differently, according to Michael Useem, a management professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School and author of The Leader’s Checklist. CEOs of public companies behave more like elected politicians, he says, and recognize that “any inference about their private behavior is fair game for reporters.”

Hedge fund directors, in contrast, often operate out of the public eye, and like it that way. “There’s no fishbowl and thus you can do anything you want — no problems as long as they’re out of sight and away from people who might want a piece of you,” Useem says.

The tendency of certain hedge fund owners to buy and build these mega-mansions reflects a cultural mindset. “The rules they live by, and the world they inhabit, involve spending well. If you have the money, buy expensive wines, ski in Utah, you can own two or three large homes. You have the money,” Useem says.

Mitchell Reardon is the experiments and project lead at Happy City, the Vancouver, Canada-based international consulting firm that advises community groups and governments on city design. He sees the macrocosm effects of hedge funders building mega-houses in urban communities.

“One great thing about neighborhoods like Greenwich Village is you have quite a few people living in a small area that supports many amenities like great restaurants and parks,” Reardon says. But if you remove six apartments and replace them with one family, you get a “hollowing-out effect,” or fewer residents who can support local businesses, and the neighborhood suffers.

Ultimately, these huge homes lead to “fewer eyes on the street,” Reardon says, and that contributes to neighborhoods with less vitality and less sociability. He’s referencing Jane Jacobs, who wrote, “We are the lucky possessors of a city order that makes it relatively simple to keep the peace because there are plenty of eyes on the street.”

The problem transcends the streets of the West Village and, indeed, Manhattan, says Rutgers University urbanist David Listokin. “It’s not just taking place in historical districts but also in places such as Chevy Chase, Maryland; Greenwich, Connecticut; and East Hampton, where land is valuable and you often have larger homes being built,” he says. “As you build more expensive homes, you’re raising the price point. You’re gentrifying an area and you have to be a hedge fund manager to live there.”

Hedge fund managers may even be pricing themselves out. Cohen got his five-story Perry Street mansion approved by the city last year and demolished the existing buildings. Then construction ceased. For months the site has been a gaping, vacant hole. According to Cohen’s architects, “The project was halted due to lack of financing.”