With commodity prices on the rebound over the past 15 months, is it time for investors to join the trend?

There may never be a good time, some money managers and analysts say, as commodities aren’t a viable long-term investment. Rather, they’re a vehicle for speculation with a grim track record: On an inflation-adjusted basis, The Economist commodity-price index—which tracks agricultural commodities, metals, industrials, and energy—has returned about zero since 1871.

“Commodities aren’t an asset class,” says Atul Lele, chief investment officer at money manager Deltec International Group. “I don’t think they should be a permanent part of the portfolio.”

While Lele says it may make sense at times to own commodities for short periods to bet on price appreciation, he views them as “an input into global growth” that affects asset prices and corporate earnings. They don’t produce any cash flow of their own, he notes, making them difficult for investors to assess.

Technology has been a large contributor to the long-term weakness in commodities’ returns, as innovations drive down the cost of production. Prices drop as it becomes easier to mine for a commodity, eroding investors’ gains. Commodities are extremely volatile because supply can’t easily adjust to changes in demand, which increases as economies expand. By the time a mine is built, demand for a particular commodity may already be falling, leading to excess supply that pressures prices.

“You don’t build a mine overnight,” says Charles Lieberman, chief investment officer for Advisors Capital Management in Ridgewood, New Jersey. “Investment lags behind the cycle of demand, so you end up with booms and busts.”

There are other challenges. Investing in physical commodities generates storage and insurance costs, plus there’s the risk that agricultural commodities may deteriorate in storage. While many investors opt for commodity futures, rolling over expiring contracts can be tricky. For example, as commodity prices soared in the mid-2000s, futures prices jumped too, making the rollover more expensive. The past decade hasn’t been easy for investors.

From December 2004 to June 2015, the S&P GSCI commodity index, one of the most widely used indexes of global commodity futures prices, registered an annualized price return of 3.39 percent, compared to a 9.3 percent annualized loss on rolling over futures contracts during that period, according to a paper entitled “Conquering Misperceptions About Commodity Futures Investing,” which cited Bloomberg as the source of its data.

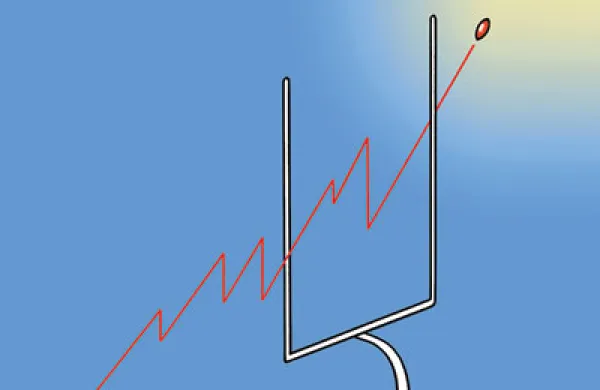

To be sure, commodities do sometimes produce super cycles, or multiple years of gains. The last one ran from 2005 to 2015, Lieberman says, when China’s thirst for commodities to build out its infrastructure fueled much of the price appreciation. But then concerns about slowing economic growth in China led to a selloff in 2015–’16.

One argument for including commodities in an investment portfolio is they provide diversification from stocks and bonds. But Philip Straehl, head of capital markets and asset allocation for Morningstar Investment Management in Chicago, doesn’t buy it. “A lot of commodity prices, such as those for energy and metals, are related to the business cycle,” he says. “They are clearly cyclical.”

Plus, with a diversified portfolio including companies in commodity-related industries, investors can use stocks to gain exposure to commodities. Stocks are a lot easier to value than commodities because companies generate cash flow.

“You can forecast and discount to present value,” Straehl says. “That’s more of a challenge for commodities.”

Looking at a miner, you can analyze its costs, its commodity mix, and the benefit from dividends and possible buybacks. But with commodities, “it’s not clear how the data interplay,” says Frances Hudson, global thematic strategist for Standard Life Investments in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Another way to gain exposure to commodities without directly investing in them is to take positions in the currencies of countries that produce a lot of natural resources. “You might go long the Brazilian real and short the Chilean peso to wipe away the Latin American risk,” Hudson says, adding that putting such currency holdings into money market instruments can earn an attractive yield, too. “The theme is sustainable income,” she says.

Generally, though, the long-term equation just doesn’t add up for commodities, according to many investment professionals. Take crude oil prices, which had dropped 63 percent to about $53 a barrel on April 17, from $145 in July 2008. The S&P 500 index, which returned almost 60 percent in the decade through April 17, is generally less volatile by comparison.

“There aren’t many ten-year periods of negative returns for the S&P 500,” says Martin Fridson, chief investment officer at Lehmann Livian Fridson Advisors in New York.