As the global financial crisis receded, Australia’s four major banks were some of the few left standing tall, thanks to relatively prudent management and a booming domestic economy. Last year Australia and New Zealand Banking Group, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, National Australia Bank and Westpac Banking Corp. were among just 14 banks worldwide to receive a AA– or higher rating from Standard & Poor’s.

The Big Four, as they are called, enjoy an oligopoly at home, but they’re vulnerable to local real estate prices and the whims of foreign investors. In 2012 they pulled in estimated total profits of almost A$25 billion ($25.6 billion) and posted returns on equity of about 20 percent, more than double what their peers in Europe and the U.S. can expect.

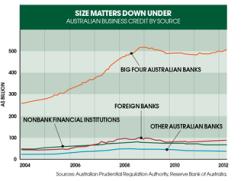

The quartet make up 8 percent of the value of Asia ex-Japan stock indexes and more than one third of the Australian market, according to Brian Johnson, a Sydney-based banking analyst at Asia-Pacific brokerage CLSA. Locally, they’re more dominant than ever: Since late 2008 their share of home loan approvals has jumped from just over 60 percent to almost 80 percent. Commonwealth is the largest of the four and the most domestically focused; the others have a substantial presence in the U.K., Asia and the U.S. Commonwealth’s stock closed at A$65.12 on February 11, up 30.6 percent from a year earlier. Westpac gained 34.1 percent over the same period, ANZ 29.6 percent and National Australia 7.8 percent. In 2013 the four’s average price-earnings ratio will be 12.5, according to Sydney-based Macquarie Securities Group, versus projections of about 9 for JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Deutsche Bank.

“The banks’ oligopoly structure has meant investors enjoy strong returns without the associated risk,” says Scott Manning, a banking analyst at JPMorgan in Sydney. “But their recent outperformance has not corresponded with an improvement in earnings at an operation level,” he warns. Between 2010 and 2012, average earnings per share fell from about A$12.50 to A$11, according to JPMorgan, which projects that they will grow by 2 percent this year.

The Big Four are also more reliant than many peers on wholesale funding, much of which comes from offshore. As of last June, Australian banks’ wholesale funding amounted to 34 percent of liabilities, compared with less than 20 percent for their European counterparts, the Reserve Bank of Australia reports. That’s actually an improvement. The banks have boosted their domestic deposit bases of late, but the competition for deposits has hiked rates, squeezing net interest margins from 2.5 percent to 2.25 percent between 2005 and last year.

Meanwhile, Australian consumers’ newfound aversion to debt has sapped housing and business credit growth, which routinely ran at 20 percent a year before the financial crisis, to about 4 percent. Last year the International Monetary Fund recommended that the Big Four hold more capital, partly to compensate for their high exposure to mortgages and Australian house prices, which are among the developed world’s steepest in relation to domestic income.

On the positive side, the big banks hold one quarter of the country’s assets under management. “Their fund management arms, which have returns significantly above the banking divisions’, provide a big share of their profit now,” Manning says. Australia’s Superannuation Guarantee, a A$1.4 trillion pool of compulsory retirement savings, yields a torrent of fee income; the average annual management charge is about 100 basis points. Over the next seven years, the government will sweeten the pot by making workers increase contributions to 12 percent of wages from 9 percent.

In a 2009 speech former Reserve Bank of Australia governor Ian Macfarlane attributed the Big Four’s resilience to the country’s unwritten “four pillars” policy, which prevents them from being bought by one another or foreign banks. “The quiet irony is that the policy made a positive contribution to financial stability, not because it increased competition but because it reduced it to manageable levels,” said Macfarlane, who is now a nonexecutive director of ANZ.

Adam Creighton is economics correspondent for the Australian.