Raja Palaniappan worked at Credit Suisse in London as a bond trader for a number of years before deciding to go out on his own and launch an online marketplace called Origin Markets, which seeks to revolutionize private placement bond issuance by eliminating intermediaries like Goldman Sachs Group. Although American by nationality, Palaniappan decided to open his platform in London because he felt the city offered greater opportunity than New York or Silicon Valley for a new financial technology, or fintech, company (see “Former Trader Raja Palaniappan Sees Fintech Opportunity in Bonds”).

“London does have a competitive advantage in fintech because you’ve got technology in Old Street and finance on Liverpool Street and they’re about three quarters of a mile apart,” Palaniappan says, referring to two areas of the City of London financial district. “In the U.S. technology lives on the Left Coast and finance on the Right Coast, and there’s little consolidation between the two.”

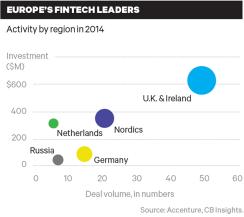

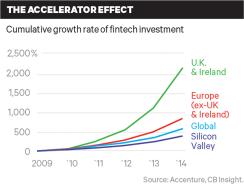

A wave of investment is following entrepreneurs like Palaniappan to the British capital. According to consulting firm Accenture, Europe is the world’s fastest-growing area for fintech funding, with spending rising 215 percent last year, to $1.48 billion. London had the largest share of that investment, some £342 million ($530 million), according to London & Partners, a government-funded agency supporting the London economy. Although the U.S. continues to lead overall fintech funding, with $2 billion in 2014, much of that was Silicon Valley–based investment in business-to-consumer start-ups like LendingTree, an online exchange that connects consumers with lenders; in London much of the activity is targeted at institutional financial services such as banking, insurance, trading and asset management.

“Since the Industrial Revolution, London has been the center for international commerce, and the melting pot that you have in terms of people and talent is pretty unique in the world,” says Sean Park, a Canadian who runs Anthemis Group, a firm that advises and invests in fintech start-ups from offices near Oxford Circus in Soho.

London’s growth as a fintech hub is not exactly surprising. The city is the world’s leading center for international wholesale financial services. It boasts more banks than Hong Kong or New York, leads the world in foreign exchange trading, has vibrant asset management and insurance sectors, and is home to the Eurobond market. In addition, fintech enjoys strong support from the British government, which sees the financial services sector as essential to the health of U.K. Plc and technology as critical to maintaining London’s competitive edge. Financial services employ some 2 million people, or about 7 percent of the country’s workforce, and generate 10 percent of the U.K.’s gross domestic product.

The government funds a variety of organizations that support what is known locally as Silicon Roundabout, offers tax incentives to investors and has streamlined regulations for start-ups — a crucial advantage in heavily regulated financial services. Officials have even promised to fast-track visas for companies seeking to import talent, though some start-ups complain about difficulties in getting software engineers into the country from Eastern Europe. In a telling indication of this political support, when a group of fintech companies recently traveled to Singapore to demonstrate their wares, the delegation was led by London’s popular mayor, Boris Johnson.

The government “wants the U.K. to lead the world in developing fintech,” Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne said last year in a speech to launch Innovate Finance, a government-funded agency for fintech investments. Osborne also announced that a government bank was doubling its investment in the sector, to $250 million. “You need the best environment, the right tax system, the appropriate regulatory rules, the best infrastructure and a government that gets out there in the world and sells your products and services,” he said.

The London fintech ecosystem currently has 70 shared office spaces with names like Huckletree, WeWork and TechHub, which rent desks and provide such amenities as gourmet coffee, video game rooms and showers to itinerant entrepreneurs. The city also boasts 36 business accelerators, which provide mentoring as well as office space. The accelerators are sponsored by companies ranging from Techstars, a Boulder, Colorado–based outfit, to Barclays Bank. Virtually every night there is a conference or gathering devoted to fintech development, attracting visitors from Silicon Valley, New York and continental Europe.

London’s greatest advantage may be its people. According to London & Partners, fintech already has 44,000 workers in the capital, more than in New York or Silicon Valley. And unlike in the U.S., where many tech start-ups are founded by 20-somethings hoping to overthrow an entire industry, in London a considerable number of fintech companies are being founded by midcareer financial professionals with a working knowledge of financial services firms and markets. They are often seeking to create technology solutions that can be used by big institutions, not compete with them.

“The entrepreneurs here are a little more experienced, and a lot of people have left established organizations,” says Eric Van der Kleij, CEO of Level39, a fintech accelerator financed by Canary Wharf Group, the property company that operates the financial district in the Docklands area of East London. “They’ve seen why ‘know your customer’ is difficult, they see why compliance is difficult, and so they come here to build a better mousetrap with all the knowledge and insight of what’s relevant for their industry.”

Although London has many advantages over other jurisdictions, the fintech sector there also has two notable disadvantages. The U.K. lacks the depth and scale of venture capital funding available in the U.S. And for companies contemplating an initial public offering, the London Stock Exchange’s AIM marketplace lags far behind the Nasdaq Stock Market and the New York Stock Exchange for helping start-ups emerge as publicly listed entities.

“It’s certainly easier to raise funds in the U.S.,” says Paolo Malaguti, an Italian who is launching a start-up called Aston Corp. Analytics to provide credit data on leveraged loans to institutional investors. “The approach here is much more conservative. I want to go to the U.S., but I’m not ready yet.”

A former banker in leveraged finance for Japan’s Mizuho Bank in London, Malaguti hopes his start-up’s online platform will replace data rooms as a required component of due diligence in the leveraged-finance business.

Yet there are signs that established institutions are helping the fintech sector address these issues. Eleven big international banks are based within walking distance of Level39’s offices, on the 39th floor of One Canada Square, the central tower in Canary Wharf. These banks have gotten the message that if they don’t participate in fintech, they might lose business to more-agile competitors. Spain’s Banco Santander has set up a $100 million InnoVentures fund in London, and HSBC Holdings has created a tech fund to invest in start-ups. UBS has established a London lab to study blockchain, the technology behind Bitcoin that many technologists believe will transform a wide range of payment services, making them more secure. Even China’s Alibaba Group Holding is getting into the act: The e-commerce giant has set up a tech laboratory in London for Alipay, its online payment service, to develop online payment tools for merchants as well as applications for airline ticketing, utility payments and virtual gaming.

Santander InnoVentures “emphasizes big data applied to specific problems and digital delivery of financial services — things that change the way our clients consume financial services,” explains Mariano Belinky, the outfit’s managing partner. One of the venture’s early investments was a company called MyCheck, which processes payments for the hospitality industry. “We focus on fairly early-stage investments, such as A or B rounds, that we can take to our clients or use ourselves,” he says.

James Stickland, who heads HSBC’s fintech efforts in London, says the ferment of activity is fostering a new atmosphere of cooperation between tech start-ups and big financial firms. “Two years ago every fintech company wanted to take down a bank,” he says. “Eighteen months later the institutions are now saying there is a degree of opportunity to partner here: You guys are supersmart and can create something new — why don’t we work together to offer a better, more cost-effective experience for our clients?” Stickland declined to confirm reports that HSBC has invested $100 million in fintech.

Barclays has taken a different approach. Instead of investing directly in start-ups, the bank last year set up an accelerator in cooperation with Techstars in a renovated warehouse in Mile End, a once-shabby area of East London that’s on the rise. The accelerator provides mentoring and a chance to have a big bank as a customer; Barclays does not invest in the start-ups, but Techstars takes a small stake. Barclays plans to open similar accelerators later this year in New York and Hong Kong. Derek White, the American who heads Barclays’ digital initiatives in London, says he believes that start-ups need clients more than they need investment help and that Barclays can be a great potential client for many of them.

“We find that when we engage the big consultants and large technology providers, we get the recycled thinking of what all of our peers are doing,” White says. “We wanted to engage really disruptive entrepreneurs directly, so we set up this physical space. Then we go and identify strategically the technologies that we think can, and will, disrupt our industry.” Barclays acquired one start-up company, Tryum, to work with its Pingit mobile payments network and try to integrate it into the bank’s customer platform.

Greg Rogers, the American Techstars executive who runs the Barclays accelerator in Mile End, says banks like Barclays are facing “death by a thousand cuts” because each of the new start-ups can take away a tiny slice of their business. “The large incumbents are coming to Techstars and they’re saying, ‘We need a strategy for how to think about partnering with outside innovation’ because there’s a recognition on the part of the incumbents that with this acceleration of entrepreneurship, most innovation is going to happen outside of their walls,” Rogers says.

Julian Skan, the Accenture executive who heads the firm’s London fintech accelerator, says the banking industry cannot be entirely replaced by digital companies, as is happening in some other industries, because of legacy regulation and customer stickiness, so banks will have to adopt some of the disruptive technology themselves.

“We believe that roughly 80 percent of the value that will be delivered by digital disruptions needs to be delivered by getting the existing players to provide those services,” Skan says. “If a business which is very safety-conscious, legacy-oriented and risk-averse is asked to adapt to digital technology, that’s going to be a huge change of culture, investment focus, talent, and they’re going to need a lot of help to do it.”

There’s no shortage of eager enterpreneurs from across Europe trying to provide that help. One is Van der Kleij, the Dutch-born CEO of Level39. Entering the accelerator is like walking into the bar scene in the original Star Wars movie, with people from a diverse range of cultures speaking a babble of foreign languages in open-plan, communal work spaces. “One of the great things about London is that diversity adds to innovation,” says Erkin Adylov, an entrepreneur from Kyrgyzstan who founded a start-up called Behavox to monitor employee communications for compliance departments. “There are only two Brits on the whole floor here.”

Van der Kleij says one of London’s great strengths is the knowledge and experience of the City’s workforce. “We have generations of talent that have gone through the financial services sector and are continuously feeding it,” he says. “From our academic institutions, people traditionally get hoovered up by the major financial services companies. This has created two advantages: a huge talent pool and a knowledge pool, which is reflected in the maturity of the institutions here.”

That environment has fostered the rise of entrepreneurs who are creating services designed to be used by existing financial services players to cut costs and streamline their businesses. Examples include DueDil, which provides online research assistance to analysts and compliance departments; Acturis, a front- and back-office system used by brokers and underwriters in the insurance industry; and Algomi, which makes bond-trading software for banks and institutional investors.

One idea gaining traction in the financial community is to develop software solutions that can become a common standard, rather than developing proprietary software for only one company. “Banks are recognizing that to adopt these things they need to collaborate more,” says Accenture’s Skan. “If distributed ledger technology is going to be used in the trading life cycle, it will take more than one bank to say they’re going to do it.”

A surprising early player in the London fintech world is the Financial Conduct Authority. The U.K. regulatory agency was once considered a staid, conservative overseer, but to help support the government’s campaign on behalf of fintech, the FCA last year established what it called the Innovation Hub, with a staff of seven and a budget of £30,000.

The Hub is designed to help start-ups determine whether their activities will need to be regulated; this can be crucial to a company’s efforts to raise venture capital and find clients. Although the FCA gives companies a quick indication of whether they would fall under regulation, it does not allow them to share this “informal steer” with third parties because of the limited information involved, says FCA spokeswoman Meredith Barker.

So far, the FCA has provided advice to 276 companies and accepted 171 in its formal program, which gives legal advice and reviews an organization’s business plan to determine which permissions the company needs to carry out its business. “The whole service is pretty revolutionary and was basically set up as a start-up within the FCA — not an easy thing to do in any regulator,” says Angus McLean, a partner at London law firm Simmons & Simmons who specializes in fintech. “This is one way the legal and regulatory landscape is favoring the growth here.”

The government is also lending a hand with two other programs — the Enterprise Investment Scheme and the Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme — that provide tax relief for individuals investing in fintech companies. The Seed Enterprise strategy gives investors 50 percent tax savings on profits earned from investments of up to £100,000 in start-ups.

The U.K. Treasury has sought to promote the fintech environment by launching a digital currency consultation to consider ways firms could move money digitally in a more efficient manner using technology similar to Bitcoin, and a payment systems reform designed to allow new players access to the U.K.’s banking payments system, says Claire Cockerton, CEO of ENTIQ, a digital investor and adviser. Now when a bank rejects a small-business loan, it is required to provide a referral to one of the new breed of peer-to-peer lenders, according to the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act, which is in the process of being implemented after being enacted earlier this year.

For all the benefits London offers to young companies, start-up financing remains a sore topic. Only a small number of local firms offer angel or venture capital funding to the sector, despite its growth potential; much of the funding comes from U.S. venture firms or international companies.

“I think it’s cultural,” says Anthemis’s Park. “In the U.S. most of venture capital’s limited partners are pension funds, university endowments, family offices or high-net-worth individuals, and those either don’t exist to the same extent in Europe or the U.K., or the risk profiles that they’re looking at tend to be much, much more conservative.”

U.K. universities are public institutions and don’t have large endowments like their U.S. counterparts. Family office wealth tends to be held by the descendants of entrepreneurs who earned their money shortly after World War II, and those investors aim for preservation of capital rather than the rapid growth that can come from investing in start-ups.

“When I talk to U.S. venture capital firms, they always say that we are not asking for enough money,” says one start-up entrepreneur. “It’s a completely different world than in the U.K.”

With London & Partners estimating that fintech investment in London reached $472 million in the first half of 2015, venture capital is clearly starting to flow at a significant pace, although the amount still lags far behind what Silicon Valley is raising for fintech in the U.S.

Another major obstacle facing start-ups: limited exit possibilities relative to the U.S. market. Lending Club, a San Francisco–based peer-to-peer lender, was valued at $8 billion on its first day of trading on the NYSE, in 2014. By contrast, no single company raised more than $100 million last year with an IPO on the LSE’s AIM market.

Analysts say the valuation gap reflects two key factors. The first is the sheer size of the U.S. market, which makes consumer-focused businesses like Lending Club more valuable than their U.K. counterparts. In addition, U.S. investors have much more experience investing in tech start-ups than their U.K. and European counterparts; this also tends to generate higher valuations.

“For us the decision is simple: Move to the U.S. and achieve our goal of being a publicly listed company, or stay in the U.K. and somehow develop as part of the ecosystem,” says Behavox’s Adylov, who like many fintech pioneers is staying in London to build his customer base and refine his concept before deciding whether to move to the U.S.

The exit experience in the U.K. is still pretty grim. The U.K. had 19 tech IPOs in 2014, according to website TechMarketView, but none was a fintech company. Many of the IPOs were by companies operating fairly simple web-based services like selling washing machines or takeout food.

So alarmed is the government by this state of affairs that the Information Economy Council, a joint industry-government body, commissioned Sherry Coutu, one of the country’s leading venture capitalists, to suggest ways of improving the situation. Coutu said the government needed to put more emphasis on scaling up small companies to become global players — not just on helping start-ups. Her Scale-Up Report called for more investment by the British Business Bank, a government lender; allowing individual savings accounts, akin to U.S. individual retirement accounts, to invest in start-ups; and increasing the maximum amount venture capital trusts can invest in individual ventures. But Coutu’s report didn’t prescribe any solutions for the relative dearth of IPO opportunities for fintech start-ups.

With dim prospects for going public, many fintech companies are focusing on an industry sale. Accenture’s Skan says the buyers will more likely be financial industry service providers like Accenture or British financial consulting firms HCL Technologies and Emphasis than the big banks, which he says are loath to make long-term investments in technology that may be overtaken quickly.

“In many cases banks will try not to buy the company but license the technology,” Skan says. “They will buy the code, deploy it and then kick it out in a year’s time if something better comes along.”

The result is that London has a thriving start-up culture in the financial services field, with many more resources devoted to helping young companies get going. But if the U.K. hopes to produce global players along the lines of PayPal Holdings, it will have to make the exit strategy more appealing.

The country already has the talent, in ventures such as currency platform TransferWise, peer-to-peer lenders like Zopa and online investment management firm Nutmeg. It now needs to find ways to allow companies like these to grow from local heroes to international stars without leaving British shores. •