Nearly a decade ago, Bill Gross, an esteemed fellow bond market investor, wrote a fascinating commentary in which he argued that General Motors served as a “canary in the coal mine” for the U.S. economy as a whole, as both the automaker and nation shared the similar challenges of uncompetitive labor costs and large, unfunded future liabilities. Of course a great deal has happened since then, as GM suffered a bankruptcy/bailout in the midst of a global financial crisis, the U.S. witnessed a credit rating downgrade, and the euro zone has lurched from one crisis to the next.

As we look at the economy today, however, another firm stands out as a better metaphor for the changes we see taking place, and, perhaps ironically, it is another auto manufacturer: Tesla Motors. Tesla is a firm that is clearly helping reshape its industry: It is unsettling established sales channels and is producing innovative technologies with profound implications for both transportation and energy storage. In a real sense, Tesla is an exemplar of the kind of firm that is developing innovative technologies that hold the potential to disrupt large segments of the economy and drive growth in the U.S. for years to come.

Of course this is to say nothing of the likelihood of the firm’s eventual success or of the valuation of Tesla’s stock price, which are issues on which we will not opine here. It is the disruptive nature of the technology that is of primary interest to us, particularly its influence on the areas of employment and inflation. As a case in point, the use of automation in the manufacturing process — machines working rather than people — is already affecting labor markets. Here Tesla is a leader, with robots already playing a very significant role in assembling its cars.

More generally, the shift toward increased technology spending by corporations has also weighed on employment, with productivity gains requiring less head count overall and suppressing wage growth broadly. That is a bit of a paradox, as historically speaking increased corporate productivity has led to greater levels of hiring, but that appears to no longer be the case, which we think owes in part to this technology substitution. Of course this dynamic does help mitigate the challenges of uncompetitive labor costs and unfunded future liabilities (as robots can work around the clock, with minimal additional marginal cost, and do not require health care or pensions, although, to be sure, maintenance costs need to be considered). Just as clearly, however, this situation raises many questions about the jobs and earnings prospects of middle-skilled workers in such an environment, particularly at a time when median wages have been stagnant and income inequality on the rise.

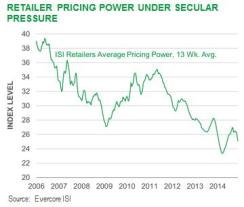

Further, Tesla’s model of selling its cars online, with limited showrooms around the country and virtually no advertising budget, is disrupting the traditional car dealer system of auto distribution in a manner that is somewhat analogous to broader trends in online retailing versus brick-and-mortar stores. In truth, however, because of its massive scale and market dominance, Amazon would better serve as an exemplar here of the prime disrupter of consumer retail markets. And, indeed, the use of Amazon for the purchase of many items formerly only available locally, along with the advent of various price comparison applications, has resulted in a tremendous degree of price transparency for U.S. consumers. In turn, this has the natural economic consequence of reducing retailers’ pricing power (see chart), which contributes to the disinflationary influence we think is the hallmark of technological advance today and is not adequately accounted for by either policymakers or investors.

In many respects, the 15 years that have elapsed between 2000 and today represent the difference between technological potential and its realization, obscured by the dot-com market collapse and the 2008–’09 financial crisis, and it is in that light that we should consider the potential of technological disruption. Whereas Tesla’s production numbers are still quite small when compared with gas-driven auto alternatives, the firm’s production schedule at the end of 2014 had already far outstripped the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s long-range electric vehicle forecasts from late 2011. That is to say, this market is growing far more rapidly than many had anticipated only a few years ago.

In fact, Morgan Stanley research now projects that in the U.S. electric vehicles will grow from less than 1 percent of the automobiles on the road to about 5 percent by 2025. If those projections prove accurate, it could lead to a reduction in oil demand of about 7 billion gallons per year, or a loss of about 4 percent of total U.S. demand. Future demand reductions resulting from greater electric vehicle adoption are not a factor commonly cited to explain recent oil price declines — although from a secular standpoint, they clearly have important implications for the future price of oil and, by extension, the future rate of inflation.

Of course, oil prices have declined in part because of remarkable extraction technology, which has brought significant new supply to market and represents the process of creative destruction in a very pure form. Tesla’s initial popularity can also be seen as an embodiment of this dynamic, as well as the growing recognition of the need for environmentally friendly alternatives to the internal combustion engine. Further, lower oil prices represent nothing but good news for the U.S. economy — particularly for lower- to middle-income households. It would be a mistake for policymakers to describe this “positive disinflation” as a concern or as a reason to hold onto excessively easy policy for too long. In truth, consumers’ real disposable income growth is what matters, and that has been on the upswing since oil’s recent swoon.

The upshot for investors is that as inflation rates remain muted across the developed world, central banks will be able to keep policy rates low for a long time yet (in particular, in the euro zone and Japan), even as the Federal Reserve in the U.S. begins the process of rate normalization near midyear. And although a world awash in policy-derived liquidity can see lower market volatility for a time, we also believe it produces significantly distorted asset prices that may eventually result in added systemic risk and a much more severe repricing of risk than might have been the case, had markets been allowed to function normally.

As a result, we are taking a barbelled approach to portfolio risk by maintaining exposures to high-quality securities, such as U.S. Treasuries and municipals (biased toward the long end of the yield curve and short in the front end), alongside more equitylike risk in the form of high-yield bonds and selective emerging-markets debt. We are firm believers that technology today is revolutionizing the economy in ways that will impact key macroeconomic drivers, and if investors do not account for these changes in their outlooks, they may discover that their investment process is on the fast lane to obsolescence.

Rick Rieder, managing director, is chief investment officer of fundamental fixed income and co-head of Americas fixed income for BlackRock in New York.