Investors are wondering whether the bull run in U.S. equities is over. With the economy gathering steam and interest rates likely to head higher, we think stocks are still the best game in town — and value stocks neglected in the recent rally look even better.

What’s backing our confidence? The Federal Reserve has made monetary tightening contingent upon a well-entrenched economic recovery. We also see corporate profits staying fairly resilient, or even improving, as a demand-fueled resurgence in sales growth combines with already lean cost structures. Under such a scenario, we would expect U.S. stocks to reclaim leadership from bonds, even given today’s elevated stock valuations.

That was also the conclusion of our capital markets forecasting model, which considers historical relationships and current conditions to generate thousands of possible market outcomes across assets. It forecasts the median annual return over the next ten years for a 100 percent U.S. large-cap stock portfolio at 6.6 percent, below the historical pace but well above the 2.8 percent median return for the seven-year U.S. Treasury bond. Even the model’s worst-case scenario for stocks — annual gains of 2.4 percent — nearly matches the median case for bonds.

The long-term performance advantage we see in stocks is largely a by-product of the market’s postcrisis gorge on safe assets. Allocations to bonds and cash are well above historical norms. Of course, most investors want and need the relative stability, income and diversification benefits that bonds can provide. But portfolios overladen with bonds may feel less safe as strengthening economic growth puts upward pressure on interest rates. In this setting, the best offset to bond risk may be stocks.

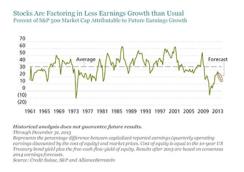

Of note: Stocks don’t seem to be pricing in excessive hopes for profits. Our research found that even after the recent rally, expectations for future earnings growth accounted for only about 15 percent to 20 percent of the S&P 500 index’s value, or just about half the 34 percent average since 1961 (see chart 1). As economic growth picks up, investors are likely to ascribe more value to future earnings, lifting stock prices. And with the Fed linking the path of interest rates to economic vigor, gains in stocks are likely to be accompanied by losses in bonds.

In our analysis, value stocks offer even greater upside potential than stocks generally. The most expensive quintile of U.S. stocks trades at 10.8 times book value — the highest absolute level since 1965 and four times higher than the S&P 500’s multiple — a record premium. Meanwhile, the cheapest quintile of U.S. stocks sells at 1.2 times book value, a 56 percent discount to the market and roughly in line with the historical average in absolute and relative terms. By concentrating on the cheapest stocks and avoiding the most expensive ones, investors have a good chance of beating the market over time. Indeed, given the enormity of this valuation gap, we believe that the odds of success for deep-value strategies have rarely been better.

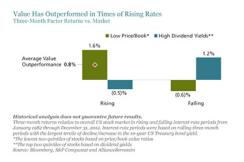

Value stocks also offer more diversification benefits versus bonds than stocks do in general. After years of underperformance, high-beta, cyclically sensitive stocks dominate the value realm, making such equities far more sensitive than usual to broad economic trends. Moreover, according to our research, 95 percent of the returns of low price-to-book stocks since 1982 have come from multiple expansion (or growth-driven repricing). That compares with 59 percent for high-dividend-paying stocks. What’s more, in a period of rising interest rates from 1982 through 2012, cheap stocks beat the market by an average of 1.6 percent, on a rolling three-month basis. That’s twice their average outperformance for the full 30-year period (see chart 2). High-dividend-yielding stocks have trailed the market by 0.6 percent.

For the past several years, investors’ desire for safety has eclipsed their desire for higher returns. But as interest rates begin to normalize, we may be reaching the point at which investors can find the safety they crave where they least expect it: in value stocks.

Joseph G. Paul is chief investment officer of U.S. value equities at AllianceBernstein.

See AllianceBernstein’s disclaimer.

Get more on equities.