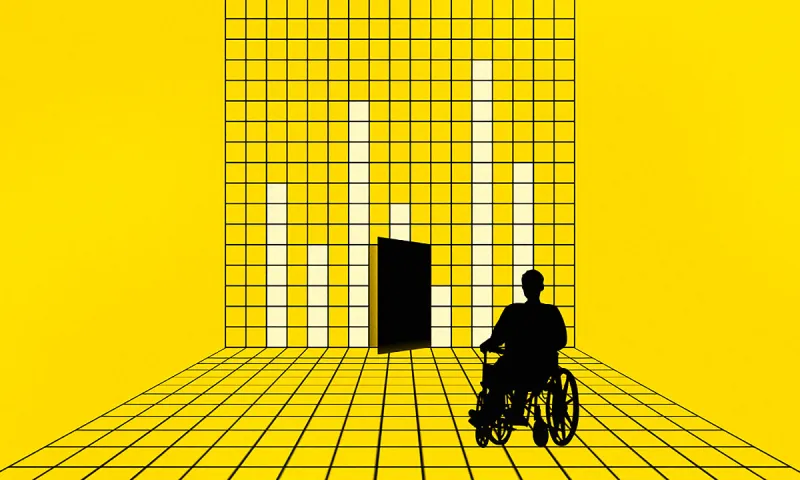

Illustration by II

“Oh no,” the recruiter exclaimed over the phone during my job interview.

Up until that moment, the conversation had progressed extremely well. I was about to be connected to the hiring manager at a financial data and technology firm. The tone changed in an instant, as if I’d mentioned interning for Bernie Madoff or demanded access to the corporate jet. But I’d said something worse: I have a disability, and asked what accommodations might be available, such as telecommuting. “We… we can’t offer any accommodation,” the recruiter stammered. Before I could respond, she gave me a curt goodbye and hung up.

I have spinal muscular atrophy. Due to my neurological condition, I need certain assistive technology tools and accommodations to work. If you’re like most of the recruiters and financial managers who interviewed me in 2013–14, you just stopped reading this article and tapped your browser’s back button.

If you’re still reading, thank you. These are my experiences as a disabled investment professional.

Since I completed my master’s in finance over six years ago, I’ve been interviewed for many jobs in the investment industry and related niches. Only one of those interviews, which was for an unpaid internship, led to any actual employment in finance. That particular internship evolved into an equity research associate position — a job that was eliminated within a year when the firm downsized.

You might be thinking I’ve identified an HR problem instead of a flaw in the culture of finance. My experience, however, indicates the hesitancy to hire the disabled is primarily a finance issue. While I was sometimes nixed as a candidate by recruiters and HR employees, as in my opening story, I frequently passed the initial interview only to be told that a firm’s partners or a department manager vetoed hiring me.

I recall one very positive interview with a real estate investment firm that was looking for someone to manage their financial models, one of my strengths. The HR manager said she would recommend me for the position as a telecommuter. I just needed to A) match my work hours to theirs (I’m in Virginia and the firm was in California) and B) visit the main office on the coast for meetings and “team-building” one week a year. I happily accepted those conditions, as visions of surf and sand danced through my head. “It’s important that you and the rest of the team feel connected,” the HR manager explained. She proceeded to describe the typical end-of-meeting-week party, which must have been quite an experience… and a hefty bar tab.

A few days later, I learned that the firm’s partners had decided that I wouldn’t be hired. “I tried,” the HR manager said, adding that management wanted someone they could watch over. This line of reasoning had become familiar, although I sincerely doubted that executives spent much time staring at spreadsheet jockeys in the office.

Perhaps I seem disgruntled, but that’s not me. I’m not simply a complainer, and this situation isn’t just mine. It’s also solvable — and profitable for those who do.

First, some facts. According to Access4Employment figures, people with disabilities:

- Have equal or higher performance ratings than their non-disabled colleagues

- Have higher retention rates and less absenteeism

- Are a significant portion (1 in 5) of America’s talented pool of job seekers

Disabled employees can relate better to customers with disabilities, who represent $1 trillion in annual aggregate consumer spending. During one job search, I reached out to several financial advisors who specialized in serving families with disabled children. No luck.

Furthermore, employers who hire people with disabilities benefit from a number of tax and financial incentives.

Now that I’ve given you some data, I have a trio of recommendations to open more investment jobs to people classified as “handicapped”:

- Integrate efforts to hire more disabled people into existing diversity programs. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel. Don’t create new offices that will likely end up on the chopping block the next time costs need to be trimmed.

- Increase telecommuting opportunities. Disabled workers likely have assistive technology and accessible spaces at home. Why not let them use their own tools in their comfortable environments? Besides, Owl Labs has noted, “companies that offer remote-friendly options see 25 percent less turnover than those that do not.”

- Network with assistive technology consultants and with people who can feed qualified disabled candidates into your firm. You want to be able to support your current/new employees with disabilities and then attract more fresh talent to your firm. Entry-level opportunities are especially important to the disabled community as we often struggle to get a foot, or wheelchair tire, in the door.

In closing, let me assure you that disability ≠ fragility. A bad day in the market isn’t going to break me or any other disabled person in finance. I have a needle shoved into my cervical spine 3 times each year, sans anesthesia, to receive genetic therapy for my muscular dystrophy. Don’t think you’ll have to coddle your handicapped employees.

In addition, if you want differentiated investment ideas and portfolio allocations, you need to have a differentiated team. The best way to accomplish that goal is to build a team that includes the disabled and other underrepresented people. Diversification should be more than an investment strategy; it should be a crucial element of your firm’s hiring (and promotion) plan, too.

Nathan Yates is the owner of ForwardView Consulting and a former finance professor. He holds a master’s degree in finance from Southern New Hampshire University and tweets from @FVNate.