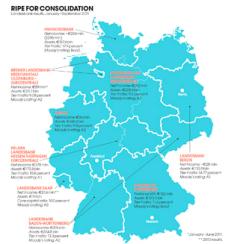

IT'S A DREARY November day, and a thick fog cloaks the 47-story Frankfurt headquarters of Helaba, a state-owned German landesbank, but CEO Hans-Dieter Brenner has a clear view of where he wants to take the lender. The financial crisis and regulatory changes have dealt harsh blows to most of Germany’s nine landesbanks, and Brenner, like many observers, believes the sector is ripe for consolidation. Within the next five to seven years, he predicts, “there will be three large regional landesbanks, covering the north, center and south of Germany.” He is determined that Helaba will be one of the survivors.

Brenner has good reason for such optimism. Landesbank Hessen-Thüringen Girozentrale, as Helaba is formally known, has turned in the strongest performance of any landesbank since the financial crisis began in 2007. The bank, a midsize lender with €172.8 billion ($220 billion) in assets, has remained solidly in the black by sticking with a conservative strategy of providing treasury and wholesale banking services to savings banks in its home territory,

With his base secure, Brenner is looking to extend Helaba’s reach within Germany. Later this year the bank will take over some €40 billion of the most lucrative assets of WestLB, the once-dominant landesbank that foundered because of poor lending and investment decisions abroad. Under the deal Helaba will supply treasury and wholesale banking services to the savings banks in WestLB’s home turf of North Rhine–Westphalia, the most populous German state.

The success of Brenner’s vision is critical for Helaba — and for Germany. The country’s economy may be performing strongly despite the pressures of Europe’s debt crisis, but the German banking system, especially the landesbank sector, is deeply troubled. Uniquely German institutions, the landesbanks are state-owned entities that operate as wholesale banks and treasuries to hundreds of savings banks, or sparkassen, across the country. Together the landesbanks and the sparkassen account for about half of all bank lending in Germany.

Many of the landesbanks expanded rashly into foreign markets in the past decade, chasing after asset-backed securities and making aggressive real estate investments only to be slammed by the global financial crisis. Four institutions — Bayerische Landesbank (BayernLB), HSH Nordbank, Landesbank Baden-Württemberg (LBBW) and WestLB — needed a total of €107.9 billion in capital injections and guarantees from their state governments and the German federal government. Despite receiving €17 billion in taxpayer aid, Düsseldorf-based WestLB was unable to return to solvency and will cease operations in July, turning its most valuable assets over to Helaba and winding down most of the rest of the bank. Munich-based BayernLB, which is 94 percent owned by the state of Bavaria after getting €29.7 billion in capital injections and guarantees, is seen as a possible candidate for acquisition.

In addition to Helaba, the most likely consolidators are Hanover-based Norddeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale (NordLB), which has adopted a conservative lending strategy similar to Brenner’s, and Stuttgart-based LBBW, which has taken some big hits of its own but remains the country’s largest landesbank, enjoying a base in the economically vibrant state of Baden-Württemberg. “In the long run, Germany won’t need more than one or two landesbanks,” says Hans-Peter Burghof, a professor of banking at the University of Hohenheim. “So the stronger landesbanks are positioning themselves to take the lead.”

Helaba owes its success to a traditional strategy of lending to locally based corporations and small and midsize companies — the vaunted German mittelstand. Revenue from lending is three times higher than that from commissions, fees and securities trading. It’s a staid but proven approach that other landesbanks, scarred by their diversification attempts, have only recently rediscovered. Helaba is “a lot more risk-averse than other landesbanks,” says Dirk Schiereck, professor of banking at the Technical University of Darmstadt.

Most banks celebrate the anniversary of their founding or a milestone merger. At Helaba, however, the bank’s institutional memory is dominated by its near-bankruptcy in 1974, when it suffered Dm1 billion (then worth about $360 million) in losses on real estate loans in Frankfurt and Munich. Whenever management considers a major loan or investment, someone invariably invokes the calamity of 38 years ago to make sure the bank doesn’t take any undue risks. “The long shadows from that crisis have extended into this century,” says CEO Brenner. “It is still very much on everybody’s mind.”

The bank’s cautious approach is evident in other ways. Helaba’s notion of an asset-backed security is a security that is based on a corporate customer’s receivables. The bank buys receivables from a pool of ten large corporate clients and then issues short-term notes for periods of no longer than nine months. In the first nine months of 2011, Helaba purchased some €1.5 billion in such receivables and bundled them into short-term securities for clients. “We use these ABSs to help our business clients increase their liquidity,” says Detlef Hosemann, Helaba’s CFO. “And we stay away from products we don’t understand.” The bank’s capital markets department does occasionally buy ABSs and collateralized debt obligations issued abroad, but it must resell them within 90 days if it cannot figure out what’s behind their structure or come up with an in-house credit analysis that matches the ratings given to the securities by rating agencies.

This conservative strategy has delivered solid results. In the first nine months of 2011, Helaba boosted its net income by 27.5 percent, to €278 million. Net interest income rose 3.3 percent, to €777 million, helping to offset an 82.8 percent drop in securities trading income, to €24 million. Thanks to its minimal holdings of government bonds from peripheral euro area countries, the bank suffered minimal sovereign losses of just €11 million, almost all of it stemming from a 50 percent haircut on Helaba’s holdings of Greek government bonds.

By contrast, Landesbank Berlin Holding posted a loss of €28 million in the first nine months of 2011, compared with net income of €181 million a year earlier, largely because of losses on its €232 million Greek bond portfolio. “Greece sank our results,” CEO Johannes Evers said when he announced the third-quarter numbers in November.

THE SYMBIOTIC TIES AMONG GERMANY'S LANDESBANKS, savings banks and state governments date to the early 19th century. Well before chancellor Otto von Bismarck unified the nation in 1871, each of the old independent German states had created a state bank to act as the treasury for savings banks and to help finance local businesses and public projects. A strong tradition of federalism continues to underpin the landesbanks today.

Defenders assert that a large, locally headquartered bank supports companies and keeps them from moving elsewhere. NordLB’s presence in Lower Saxony has been essential “to make sure that Volkswagen stays in the state,” the bank’s CEO, Gunter Dunkel, insists. If there were no landesbanks, he adds, “Hamburg, Hanover and even Berlin would have no major banks of their own.”

Critics, however, have long contended that the landesbanks’ state support gives them an unfair advantage and distorts competition. State politicians sit as prominent board members of the landesbanks and often press the banks to bid for local infrastructure projects. Germany has the most fragmented banking market in Europe,

In 2001 the European Commission reached an agreement with the German government to phase out state guarantees to the landesbanks within four years. Those guarantees enabled the landesbanks to issue triple-A-rated bonds and fund themselves at a much lower cost than their commercial rivals. The agreement didn’t produce the intended effect, though. Even after the removal of guarantees, the presence of so many large landesbanks left Germany with excess banking capacity and depressed the sector’s profitability, according to a 2010 report by the International Monetary Fund. “They should be privatized, with viable business models that are able to face the test of the markets,” said Helge Berger, co-author of the IMF report.

The removal of guarantees had an even more pernicious unintended consequence. Many landesbanks rushed to borrow cheap funds between 2001 and 2005, and then ventured abroad in search of greater profits. Few succeeded. Landesbanks gained notoriety as the dumb money eager to finance everything from overleveraged shopping centers in the U.K. to apartment towers on Spain’s Mediterranean coast to securitized subprime mortgages and collateralized debt obligations in the U.S. — all risky areas in which they had little expertise. “They had overly ambitious boards who wanted to play on the international capital markets, so they hired investment bankers — though not the best ones because the best ones were too expensive and went to the bigger, global banks,” says the University of Hohenheim’s Burghof.

WestLB exhibited the greatest ambition and suffered some of the biggest losses. The bank established a principal finance unit in London under the leadership of an aggressive American financier, Robin Saunders, and gave her carte blanche to make big investments. The unit arranged and largely financed a €1.35 billion structured loan for Boxclever, an upstart U.K. television rental company, only to see the business collapse in 2003. WestLB took a €427 million write-down on the deal and fired CEO Jürgen Sengera. Instead of reacting conservatively in the wake of that fiasco, WestLB doubled down on its diversification drive by plunging into derivatives tied to subprime mortgages in the U.S. After the subprime crisis erupted, WestLB needed €8 billion in government grants and loan guarantees in 2008–’09 to stay afloat.

In return for approving that aid, the European Commission demanded an extensive restructuring of WestLB that will lead to its breakup in July. The bank will transfer about €40 billion of its €160 billion in assets to a new entity, called a verbundbank, that Helaba plans to acquire later this year. In December, Helaba’s owners gave the green light to management to negotiate the deal. WestLB will place an additional €75 billion of mostly impaired assets into a “bad bank,” named Erste Abwicklungsanstalt, which will be run down over ten to 12 years. Any leftover assets will remain in a rump WestLB that will be renamed SPM-Bank and be 100 percent owned by the state of North Rhine–Westphalia.

BayernLB, the second-largest landesbank, also stumbled badly in its effort to expand. Eager to get into the fast-growing Central and Eastern European market, BayernLB paid €1.625 billion for a 50.01 percent stake in Austrian banking group Hypo Alpe-Adria Bank International in May 2007, just weeks before the financial crisis started and caused liquidity to dry up in CEE markets. In early 2008 the bank forced out chief executive Werner Schmidt, who had championed the deal, and in December 2009, BayernLB paid the Austrian government €3.5 billion to take Alpe-Adria off its hands. The bank also took hits on real estate investments in Iceland. The tab? The state of Bavaria injected €10 billion in fresh capital and provided an additional €19.7 billion in liquidity and asset guarantees to keep the bank afloat. The aid lifted the state’s ownership of the bank to 94 percent from 50 percent, and raised doubts about the bank’s long-term future. “They still have to clear a lot of nonperforming assets from their balance sheet,” says Helaba CEO Brenner.

BRENNER SPENT MOST OF HIS career as an accountant, which turned out to be good training. “Other landesbanks got into trouble because their chief executives wanted to be big investment bankers,” says banking professor Burghof. “Helaba’s strength is recognizing its limitations, so an accountant like Brenner is a good person to have at the top.” The CEO’s peers have a similarly positive opinion about him. “He isn’t an innovator with revolutionary ideas that shake people up,” says NordLB’s Dunkel. “Rather, he reacts well to a situation. He’s a man of few words, yet very influential.” Dunkel, for one, has bought into Brenner’s vision of landesbank consolidation in the coming years. “Not many disagree with that vision,” he says.

Brenner came to banking late in his professional life. After receiving his degree in business administration from Saarland University, he joined accounting firm Peat, Marwick, Mitchell & Co., which turned into KPMG in 1979. He remained with the firm for 22 years, the last ten as partner and head of its Frankfurt branch, KPMG Deutsche Treuhandgesellschaft, where he mainly handled banking clients. In 2001 he had just finished an exhausting due diligence process at Dresdner Bank, which was being acquired by giant insurer Allianz, when Helaba chief executive Günther Merl offered him the job of chief financial officer. “I thought maybe this was an opportunity to work less and have a more balanced life,” deadpans Brenner, a 59-year-old of medium height and build with a penchant for electric-white shirts, bright ties and dark suits.

The career change proved anything but relaxing. The year he joined Helaba was the year that Germany agreed to phase out state guarantees for the landesbanks. Brenner responded by helping to devise a risk restructuring of Helaba that would maintain a high credit rating for the bank. Helaba is jointly owned by its regional savings banks association (with an 85 percent stake) and the states of Hesse (10 percent) and Thuringia (5 percent). In 2004 the owners created a group structure under which Helaba and the savings banks function as a single economic entity with an integrated risk management system. The revamp helped Helaba win a credit rating of A from Standard & Poor’s — the highest of any landesbank. “This was meant to compensate for the loss of state guarantees,” says Brenner. And it worked. “Helaba’s funding costs are lower than for most other landesbanks,” says Christian van Beek, a Frankfurt-based analyst for Fitch Ratings, which gives Helaba an A+ credit rating.

Funding costs dropped even lower after Helaba acquired Germany’s sixth-largest savings bank, Frankfurter Sparkasse, in 2005. A landesbank taking over a sparkasse is a sensitive issue. Savings banks see a natural territorial divide between their retail and small-business lending and the wholesale banking of the landesbanks. But Frankfurter Sparkasse was a troubled savings bank that had suffered steep losses between 2000 and 2005 because of bad bets in the capital markets, including the purchase of bonds from Parmalat, the Italian dairy company that collapsed in 2003 under €14 billion in debt. With the bank at risk of going under, Helaba stepped forward as a white knight, helping the Association of Savings and Giro Banks of Hesse-Thuringia avoid an expensive rescue. For €725 million in cash, Helaba purchased a savings bank with €13.8 billion in assets and 70 branches. Frankfurter Sparkasse is the market leader in retail and mittelstand banking in Frankfurt, Germany’s richest major city, with per capita income of €76,700.

“We were still watched closely by the savings banks association — they were worried we might expand beyond the Frankfurt region,” says Herbert Hans Grüntker, a longtime Helaba executive who now serves as Frankfurter Sparkasse’s CEO. “But we turned the bank around so that the association would not have to help out financially. And they are even happier now because we are paying dividends.”

Frankfurter Sparkasse largely withdrew from the capital markets and refocused on the Frankfurt retail and SME markets. By retaining profits, it has steadily raised its core tier-1 capital from 7 percent at the time of Helaba’s acquisition six years ago to 15 percent today. And it has kept its return on equity above 10 percent. Over the past five years, Frankfurter Sparkasse’s fastest-growing segment has been its Internet banking subsidiary, 1822direkt, named after the year the savings bank was founded. The unit has more than doubled its client base, to some 400,000, and now accounts for €5 billion of the savings bank’s €14 billion in deposits. The Internet subsidiary has helped the savings bank maintain a 35 percent share of retail banking in Frankfurt, which is arguably the most competitive region in Germany, with five banks claiming market shares above 10 percent.

The savings bank acquisition has delivered the synergies that Helaba hoped to achieve. In addition to retail and SME customers, Frankfurter Sparkasse has been able to attract business clients with annual sales of as much as €500 million — unusually high for a savings bank — by offering them Helaba products and services. “If a company is growing fast and needs even more credit facilities, we turn them over to Helaba,” says Grüntker. In the first nine months of 2011, Frankfurter Sparkasse contributed €105 million to Helaba’s €278 million in net income. By providing some of their deposits to Helaba, the savings bank accounted for close to €5 billion of the landesbank’s total €14 billion in funding for the first three quarters of 2011. And both Helaba and Frankfurter Sparkasse have cut down costs by combining back-office activities.

Brenner became Helaba’s chief executive on October 1, 2008, just as global markets were seizing up in the wake of the collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings. After the past three years, his hair and mustache show more salt than pepper. Still, Helaba has had fewer worries than its peers. It ended 2008 with a modest loss of €44 million, the smallest of any landesbank, and bounced back to post net income of €323 million in 2009 and €298 million in 2010. Several larger landesbanks fared much worse. BayernLB racked up a combined €7.7 billion in losses in 2008 and 2009 before returning to the black with a €635 million profit in 2010, while LBBW lost a total of €3.3 billion in 2008 and 2009 before posting a profit of €317 million in 2010.

Like Helaba, LBBW seeks a leadership role in landesbank consolidation. In 2008 the bank paid €328 million to acquire Landesbank Sachsen Girozentrale (SachsenLB), the troubled landesbank of the eastern German state of Saxony. As part of the deal, the Saxony government guaranteed to cover as much as €2.75 billion of SachsenLB’s losses on its structured debt portfolios. Those guarantees were not nearly enough, however. The bank’s €11 billion investment portfolio was riddled with exposure to loss-making Irish real estate and U.S. securitizations, as well as large holdings of sovereign bonds from Greece and other peripheral euro zone countries. With losses mounting, LBBW’s supervisory board forced CEO Siegfried Jaschinski to resign in 2009.

In December 2009, with European Commission approval, LBBW was rescued with a €5 billion capital injection and €12.7 billion in guarantees from its owners, the Savings Bank Association of Baden-Württemberg (40.5 percent), the state of Baden-Württemberg (40.5 percent) and the city of Stuttgart (19 percent). As part of the deal, LBBW agreed to shrink its 2008 balance sheet of €448 billion by 40 percent and sharply reduce its international business. The bank is roughly halfway toward its goal, having pared its assets — mainly through sales — by some 20 percent, to €354.8 billion, by June 2011.

“They are refocusing on their region in terms of both business and retail clients,” says Fitch’s van Beek. “Looking forward, there is no reason they should not be successful in the next couple of years.” In fact, LBBW is the likely third member of the landesbank trio — along with Helaba in central Germany and NordLB in the north — that is expected to emerge from the sector’s consolidation over the next five to seven years.

“LBBW has the same strategy in the south as ours in the north,” says NordLB’s Dunkel. NordLB raised its net income to €262 million in the first three quarters of 2011 from €79 million in the same period of 2010 thanks to an even more conservative business model than Helaba’s. Net interest income rose 7.4 percent in the first nine months of 2011, to €1.31 billion, and accounted for more than 90 percent of overall revenue.

Notwithstanding its relative strength, Helaba faces challenges in fulfilling Brenner’s vision. Embarrassingly, the bank had to drop out of the European Banking Authority’s stress tests last July because of a last-minute dispute over its hybrid capital, which the EBA deemed insufficient to qualify as core tier-1 capital.

As public sector entities owned by the states and savings banks associations, most landesbanks have no conventional equity capital. But those owners provide so-called silent participations under which they agree to inject more capital whenever the bank needs it and to forgo any increase in voting rights. “Silent participation means you give your money and keep your mouth shut,” explains Peter Lutz, head of banking regulatory issues at the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority, the German agency also known as BaFin. Helaba relies on the instrument more than other landesbanks. Silent participation, most of it provided by the state of Hesse, makes up 51.7 percent of Helaba’s core tier-1 capital of €5.75 billion.

The proportion raised alarms at the EBA last summer. The agency had been widely criticized because an earlier round of stress tests, in July 2010, failed to detect problems in the Irish banking system, which imploded shortly afterward. For the July 2011 test, the EBA decided to apply stricter criteria, making few allowances for any hybrid capital at the 90 banks in 20 different countries. The move caught Helaba by surprise and led to an open shouting match between the EBA and BaFin chief Jochen Sanio, who blasted the European agency’s decision as being “without legal authority.”

Helaba and its owners appear to have resolved the issue. In November the state of Hesse agreed to convert its silent participation of €1.92 billion into a financial instrument that will count as common equity. “We are of the opinion that their silent participation now complies with all requirements for core tier-1 capital,” says BaFin’s Lutz. If accepted by the EBA, the instrument will lift the bank’s core tier-1 capital ratio to 10 percent, comfortably above the 9 percent required by the EBA and Basel III.

Helaba, like other European banks, faces a rapidly deteriorating economic climate. The debt crisis and resulting austerity measures have pushed Greece and Portugal into recession and left Italy and Spain on the brink of it. Even Germany, Europe’s strongest economy, likely experienced a slight drop in output in the fourth quarter of 2011, the Federal Statistical Office announced last month.

Yet Brenner is confident that Helaba can weather any downturn. “We have strong midcap and large-cap corporate clients, so in case of a modest recession, I would not expect high loan-loss reserves,” he says. “And in case of a bigger recession, all our peers will be hurt a lot more than we will be.”

A downturn, moreover, would only increase pressure for a faster consolidation. Brenner predicts that in addition to WestLB, at least two other troubled banks could disappear in the next few years: Landesbank Saar, based in the Saarland, along Germany’s border with France, and Hamburg-based HSH Nordbank. “And in the case of BayernLB, you have to ask yourself where its liquidity will come from now that it isn’t linked to the savings banks,” says Brenner. “This means that in all these states, the savings banks associations will have to make arrangements with other landesbanks.”

Like Helaba, for instance. • •