After lagging for years, emerging-markets equities are back in the winner’s circle. Investors are wondering, however, if this turn for the better will be long-lasting. It’s worth thinking, therefore, about how the next upcycle may unfold.

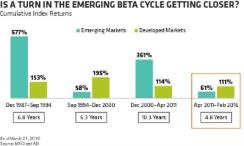

From a pure life-expectancy standpoint, the lengthy losing streak in developing-world stocks is getting long in the tooth. In the 27 years since the inception of the MSCI Emerging Markets index, there have been three such half-cycles, averaging eight years in duration (see chart 1). It’s not unreasonable to think that we may be getting closer to an extended turn in fortunes for the emerging-markets stock group as a whole.

What would make us at AllianceBernstein more bullish on the prospects for a more enduring stretch of emerging-markets beta outperformance? A walk down memory lane suggests that at least four drivers of prior upcycles will still play a part, but they will have less firepower:

Commodity supercycle. The decade-long rally that began in 2000 was largely fueled by China’s emergence as a manufacturing powerhouse and its voracious appetite for industrial commodities, which drove booms in fellow emerging-markets countries.

But commodity supercycles come around every 20 to 40 years. The last one peaked in 2010. For the next one to take shape, a large part of the globe would need to be industrializing faster than expected. That is unlikely to happen until India or one of the Southeast Asian countries start to invest more heavily in their infrastructure. Even so, with the exception of India, these smaller economies can fill only part of the growth void created by a slowing China.

Manufacturing boom. Emerging-markets growth doesn’t have to be commodity-led. Back in the 1980s, the big emerging-markets constituents were the booming economies of Mexico, Thailand, Malaysia and South Korea. There was a lot of excitement surrounding Mexico with the start of NAFTA in 1994; Malaysia and Thailand were delivering GDP growth in the double digits around the same time. Entrance into the World Trade Organization in 2001 was a huge tailwind for China and other emerging economies.

Today, the up-and-coming industrial manufacturing centers are in Mexico, Vietnam, India, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. We expect them to continue to gain from China’s waning status as a source for low-cost labor and from reviving demand from developed economies.

Yet these countries lack the workforces and physical infrastructure to supplant China, meaning that this trend is unlikely to power an extended, broad-based emerging-markets upcycle in the near term. If anything, recent events suggest a move toward greater regionalization: sanctions against Russia; the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which excludes China; and waning interest among Central European countries for joining the euro zone. The benefits from accessing new markets are likely to be much more selective than in the past.

Reform efforts. In the aftermath of the currency crises of the late 1990s, we saw widespread adoption of reforms aimed at promoting greater exchange rate flexibility, fiscal and monetary discipline and capital markets expansion. These reforms have significantly — and, to some extent, permanently — reduced the overall emerging-markets risk profile. Although such efforts are ongoing in some countries, however, they have stagnated, if not regressed, in others.

Emerging-markets innovation. The developing world is no stranger to technological innovation. Some examples of leading companies include South Korea’s Samsung Electronics Co., Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Tata Consultancy Services and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries in India and China’s Huawei Technologies Co. and smartphone maker ZTE Corp.. The list also includes fast-growing players in e-commerce, health care and personal care.

There are signs that the sell-off in emerging-markets equities has gone too far. Even after the recent uptick, the MSCI Emerging Markets index trades at one of the steepest discounts to its developed-markets counterpart in about a decade.

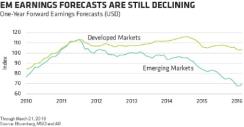

But many obstacles lie in the near-term path to a more enduring, broad-based emerging-markets upcycle. The last time the discount on emerging markets was this deep, returns on equity in the developing world were significantly higher than those of their developed-world peers. On that basis, emerging-markets stocks don’t look so provocatively cheap. The continuing decline in earnings forecasts is another hurdle (see chart 2). For a sustained beta turn, we would likely need to see a return to earnings growth.

All told, whereas we believe that the four overarching themes of the past highlighted above will remain relevant to investment success in the years ahead, the mix of winners arising from those themes is likely to be very different — and far more idiosyncratic. Finding tomorrow’s emerging-markets outperformers will take rigorous research, entailing local knowledge and global industry insights — and a discriminating eye.

Sammy Suzuki is portfolio manager of strategic core equities at AB in New York.

See AB’s disclaimer.

Get more on emerging markets and on equities.