By: Anu R. Ganti, CFA, Director, Index Investment Strategy, and Craig J. Lazzara, CFA, Managing Director, Index Investment Strategy, S&P Dow Jones Indices

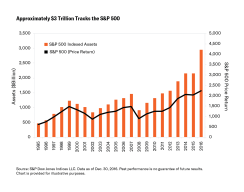

Passively managed assets have grown dramatically since the inception of indexing in the 1970s. (The chart below illustrates this for the S&P 500, arguably the most widely tracked index in the world.) Unsurprisingly, some active managers, as well as other critics, have raised questions about the impact of the growth of indexing. The charges leveled at index funds include suggestions that they encourage collusive behavior, that they are poor stewards of their customers’ assets, that they contribute to market bubbles, and that they diminish market efficiency. The authors of this paper offer rebuttals to each of these concerns, and suggest how an eventual equilibrium between active and passive assets under management might arise.

Is common ownership a bad thing?

Passively invested assets, at least in the U.S., are dominated by three large entities: BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street. They (or, in BlackRock’s case, its predecessor companies) were among the pioneers of index funds in the 1970s, and today the big three manage approximately $13 trillion.

It’s estimated that fully passive index funds manage approximately 20% of the total float-adjusted capitalization of the U.S. stock market. Assume (incorrectly, but for the sake of argument) that the entire 20% is controlled by the three largest indexers, and assume further (correctly, this time) that they also manage factor-based “smart beta” funds as well as fully active portfolios. It’s plausible, then, to argue that the big three, on behalf of their clients, own between one-quarter and one-third of nearly every large company in the U.S.

Critics claim that ownership of a substantial fraction of most or all of the competitors in an industry could lead to “softer competition among product rivals” and higher consumer prices. The most often-cited example of this putative problem is the claim that U.S. airline ticket prices are higher than need be because of common ownership. Therefore, it is argued, public policy should require that “investors in firms in well-defined oligopolistic industries…choose either to limit their holdings of an industry to a small stake…or to hold the shares of only a single ‘effective firm’ per industry.”

Let’s take a closer look at these assertions:

- There is by no means an academic consensus that common ownership has raised the price of airline tickets. Moreover, the critics’ statistics are, like any statistical analysis, indicative of correlation rather than causation. Ticket prices may have risen, and the importance of index funds has certainly increased, but without a clearly identified causal mechanism, caution should be exercised in attributing the first effect to the second.

- One company’s revenue is another company’s expense. Airlines accounted for 0.5% of the float-adjusted market capitalization of the S&P 500 as of year-end 2017. Even if index funds could cause airline executives to raise prices, why would they do so? Why increase the profits of 0.5% of a portfolio and raise the expenses of the other 99.5%? Price fixing and collusion are proscribed under applicable anti-trust laws. If such behaviors were suspected, appropriate legal remedies are presumably near at hand.

- Even if the critics are correct that indexers’ common ownership of competitors is a problem for the economy, their proposed solution may be a cure worse than the disease. The authors of this paper estimate that the passive management industry, at its current scale, saves investors more than $20 billion annually in management fees alone, a benefit that accrues to institutional and retail investors alike. Handicapping an industry that delivers benefits of this magnitude on weak evidence of an ill-defined problem might be a bridge too far.

The growth of index funds and passive management has been one of the most significant developments in modern financial history. The dollars saved by the customers of index funds – in terms of reduced fees and reduced active underperformance – now certainly must be reckoned in the hundreds of billions. This benefit did not materialize out of thin air, of course – fees saved by index customers are fees not received by active managers.

It is not surprising, therefore, that active managers would mount a stubborn resistance to the growth of index funds. Some of their commentary is risible and can easily be dismissed, but issue can be taken even with the more substantive complaints. Common ownership has not been shown to lead to collusive behavior; passive managers are not demonstrably poor stewards of their customers’ assets; if the equity market is in a bubble, it was not inflated by index funds; and there’s no evidence that passive management has damaged market efficiency. The growth of index funds in itself evidences the value that passive management delivers to the investment community.

The authors of this paper anticipate that index funds will continue to take market share from active managers. This trend may eventually diminish. An equilibrium between active and passive management would require that the majority of actively managed assets underperform by a relatively small amount, enabling a minority of assets to outperform by more.