Within global emerging market equities, as in other equity classes, there has been a significant shift within the asset management industry towards passive investing and a willingness to look away from active management. The Financial Times reported in August 2017 that exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that track emerging market (EM) assets now represent almost a fifth of total emerging market mutual fund assets, up from over a tenth just two years ago. The incremental flow of dollars to the asset class has overwhelmingly voted against active management by a factor of 2-to-1. We believe that there are three key drawbacks of benchmark investing. Long-term investors with an absolute return mindset may be wise to question the prevailing orthodoxy.

See no evil

Emerging market equities may present attractive opportunities for long-term investors, predominantly because of the positive long-term secular trend of favorable demographics. Significant projected population growth (primarily in less-developed economies), rising standards of living, and an emerging middle class offer fertile ground for investors to seek to capitalize on.

The MSCI Emerging Markets (EM) Index, the predominant emerging markets benchmark, by comparison, is constructed in such a way that it reflects where large pools of capital have been attracted or created. It does not necessarily reflect where future opportunities for long-term investors lie. The index is weighted by market capitalization, which means it is influenced by the scale of a business and its equity base. Therefore, index-based investments and returns are often shaped by company size rather than the investor having conviction in a business and its performance over the long term.

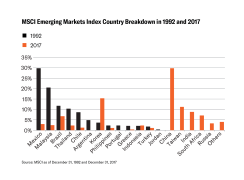

The MSCI EM index has a long track record of such distortion. As shown below, Mexico, at around 30%, was the largest country weight in 1992. This was a result of former President Carlos Salinas de Gortari’s privatization spree of large, state-controlled enterprises which attracted capital flows from foreign investors. Taking an index-based approach to EM would have left investors heavily exposed to Mexico’s then weak regulation, corruption, and political and economic instability. What followed was a mid-1990s financial crisis, which was fueled further by a credit boom and a level of inflation higher than the U.S., Mexico’s main trading partner, thus making exports from Mexico more expensive and imports from the U.S. cheaper.

Hear no evil

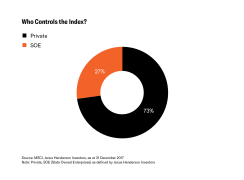

The benchmark appears to turn a deaf ear to the cacophony of political scandal and misallocation of capital by politicians. The role of the state in EM corporate ownership and its control of capital markets is significant, and we believe it has a negative impact on long-term returns. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) make up a substantial proportion of many emerging equity markets, which impacts the overall index. Our research has identified there is either significant state influence or direct control in more than a quarter of companies within the EM benchmark as shown in below. In contrast, our approach leads us to avoid SOEs, except in cases where there are joint ventures or other corporate endorsements in place that align the interests of the management team with minority shareholders.

The importance of alignment

The importance of such alignment can be witnessed with those Chinese companies involved in the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) policy. This initiative has ambitious infrastructure and economic aims, hoping to better connect China with other parts of Asia, Europe, East Africa, the Middle East, and Russia. Such global ambition requires unbounded amounts of capital, with estimates ranging from U.S. $4 trillion to $8 trillion. While the built environment – buildings and infrastructure – is able to consume such colossal amounts of capital, it is less certain that those Chinese SOEs investing in this centrally planned initiative will produce a positive return on equity for shareholders.

One example of an OBOR project that has not been successful to date is an oil refinery built in Kyrgyzstan, Central Asia, by state-owned Zhongda China Petrol. When built it could only run at 6% capacity because it could not source enough oil. While there are bound to be high-profile disappointments, the auspices and historical precedents for such investment projects do not bode well and this reinforces our belief that it is important to seek investments where our interests are aligned with those allocating share capital.

Speak no evil

The New York Times has reported that Vanguard took in eight times more inflows than the rest of the U.S. mutual fund industry combined in the last three calendar years. We believe that when investing in emerging markets through market cycles an active approach can emphasize higher-quality companies and help investors meet long-term goals. That is something to shout about in a world charging toward the siren song of passive investing in emerging markets.

Key takeaways

- Emerging markets can be risky for investors.

- Immature legal and political systems in emerging markets often mean inadequate levels of minority shareholder protection and economic volatility.

- The opportunities for investment in emerging markets, however, are significant and well documented. We believe that it calls for a selective approach to investing. The issue is that passive investing is not selective. It is not designed to filter out businesses which have poor alignment, have low return potential or which are operating in countries with a demographic headwind. It is a low common-denominator approach to investing within EM, based largely on market capitalization. We believe that it is shaped by the past and not looking to, or taking advantage of, the future. The MSCI EM index contains many companies that we feel are either too high risk or low-return businesses, which could present dangers to investors’ long-term capital growth.

The opinions and views expressed are those of the author(s) and are subject to change without notice. They do not necessarily reflect the views of others in Janus Henderson's organization and no forecasts can be guaranteed. Opinions and examples are meant as an illustration of broader themes and are not an indication of trading intent. They are for information purposes only and should not be used or construed as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector.

Foreign securities are subject to additional risks including currency fluctuations, political and economic uncertainty, increased volatility, lower liquidity and differing financial and information reporting standards, all of which are magnified in emerging markets.

When valuations fall and market and economic conditions change it is possible for both actively and passively managed investments to lose value.

MSCI Emerging Markets IndexSM reflects the equity market performance of emerging markets.

Janus Henderson is a trademark of Janus Henderson Group plc or one of its subsidiary entities. © Janus Henderson Group plc.