Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing’s plan to allow companies with dual-class shares to list this year has drawn rebuke.

David Webb, an adviser to Hong Kong’s top market regulator, the Securities and Futures Commission, is among the well-known investors in the city to strongly criticize HKEX since its announcement last month to expand its listing regime.

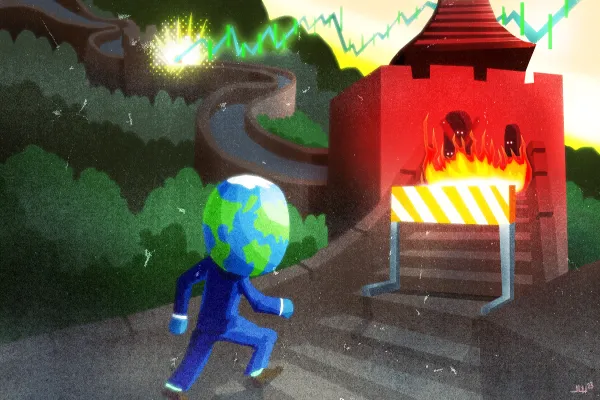

“This policy is about racing to the bottom, attracting any crappy company we can by dismantling shareholder rights,” Webb, an independent investor and deputy chairman of the SFC’s takeovers and mergers panel, said in an email. “It makes us look more like the Wild East, a sunny place for shady companies. No quarterly reporting, no accountability and no class action system, prohibiting access to legal remedies.”

HKEX is trying to attract top Chinese technology companies run by entrepreneurs, after losing the initial public offering of Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba Group Holding to the New York Stock Exchange about three years ago. HKEX Chief Executive Officer Charles Li sees the exchange operator’s move to expand its listing pool as a progressive way to compete for business.

“The Hong Kong market has decided to take a big step forward and secure our relevancy as a premier global capital formation center,” Li wrote in a December 15 blog. “Following an extensive market consultation, we have reached a clear consensus that Hong Kong must broaden its listing regime and proactively embrace the new economy.”

Li was not available for an interview.

While controversial, not all disapprove of HKEX’s move to accept dual-class listings. Auditing firm PricewaterhouseCoopers said in a January 2 statement that the exchange operator’s new policy could help turn Hong Kong into the world’s largest IPO market in 2018, possibly raising as much as HK$250 billion ($32 billion).

The step “will attract more companies to seek IPOs in the Hong Kong market,” PwC said.

Hong Kong ranked No. 2 globally in IPO volume in 2017, behind the NYSE, according to data research firm Dealogic. In late 2013, Alibaba executives had weighed whether to go public in Hong Kong or New York, choosing the U.S. where it found more flexibility around management voting rights.

Alibaba’s decision to list on the NYSE in September 2014 — in the world’s largest IPO ever — prompted Li and HKEX to embark on a three-year market consultation. During that time, they lobbied Hong Kong regulators to change rules prohibiting companies from giving management more voting rights than outside shareholders.

Hong Kong regulators initially objected to HKEX efforts. “The SFC is of the view that Hong Kong’s securities markets and reputation would be harmed” if weighted voting rights structures became common, the regulator said in a June 25, 2015 statement on its website.

But Webb says Li has won over the Hong Kong government in the past few years. “The government is fully on board with this, having pulled the plug on the SFC’s proposals to establish a listing policy committee to reform the rules,” he said. By siding with HKEX, he said the government has in “effect shredded” the SFC’s previous rulings on the matter.

“It simply isn’t true that we need to reduce shareholder protections to attract ‘innovative’ companies,” Webb said. “A recent wave of tech listings including Razer and China Literature prove otherwise.”

Razer, a mobile game device manufacturer backed by Intel and Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing, and China Literature, the e-book unit of Chinese internet giant Tencent Holdings, each chose to go public in Hong Kong instead of New York.

Allowing dual-class listings is not yet a done deal, but regulators likely will amend listings rules in the coming few months after a final round of market consultations, according to HKEX’s Li.

“By lowering our standards, we will ultimately lose listings to places with higher standards where investors will pay more for good companies that are willing to comply with those standards,” Webb said.