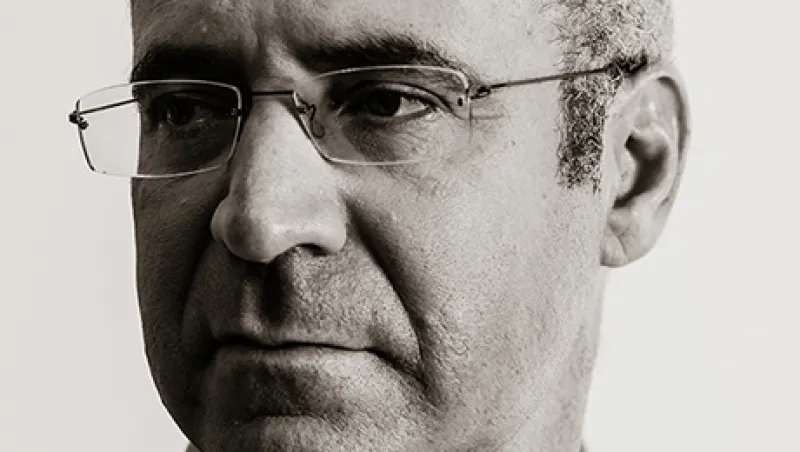

Bill Browder can’t get enough publicity. As head of Hermitage Capital Management in Moscow in the late 1990s and early 2000s, he used the media to expose rampant asset-stripping at Gazprom, the giant Russian state oil and gas company, and made a killing when the government of President Vladimir Putin intervened on behalf of shareholders.

Today, Browder, 50, is a sworn enemy of Putin, and he’s betting that publicity can keep him alive and achieve a measure of justice for his friend and lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, who was murdered for exposing high-level corruption in Russia.

The broad outline of Browder’s rise and fall as the most prominent Western investor in post-Soviet Russia is well known, but he recounts it in riveting detail in his new book Red Notice: A True Story of High Finance, Murder, and One Man’s Fight for Justice.

Writing a book was “harder than anything I’ve ever done — it’s easier to manage a hedge fund,” Browder says in an interview during a book-tour visit to New York from his home in London. Determined that his book wouldn’t sit unread like the stack on his bedside table, he enlisted his son, David, 18, as an informal editor, passing him a chapter at a time for feedback. “If I could keep him interested,” he explains, “I knew I could probably keep the world interested.”

Does he ever. Browder’s tale is both an improbable story of personal discovery and a damning exposé of Russia’s descent into a lawless kleptocracy under Putin.

A scion of a leftist Midwestern American family (his grandfather Earl Browder headed the Communist Party USA in the 1930s and ’40s), Browder rebelled in his youth and decided to make his mark as a capitalist, earning an MBA from the University of Chicago and going to Russia to seek fame and fortune. A 1992 investment banking assignment for a fishing fleet in Murmansk opened his eyes to the potential: The country’s privatization voucher program valued all of the companies in Russia — today the world’s eighth-largest economy — at just $10 billion.

Browder launched Hermitage in 1996 with $25 million from the late financier Edmond Safra. Thanks to street smarts and dogged research, he unearthed massively underpriced shares and turned Hermitage into the world’s best-performing fund, with $1 billion in assets at the end of 1997. Russia’s 1998 default nearly wiped him out, but Browder clawed his way back, winning two unlikely battles along the way: defeating oligarch Vladimir Potanin over a dilutive bond issue at oil company Sidanco (now part of state-controlled Rosneft) in 1998, and facing down Gazprom over the stripping of billions of dollars’ worth of gas assets in 2001.

“These guys were all strutting around like they were the baddest-ass guys around, and in fact their bark was much louder than their bite, I thought,” he says. “I gained perhaps too much confidence from that situation.”

Browder’s biggest mistake was considering Putin to be an ally. The president had tipped the Gazprom case in Hermitage’s favor by sacking the company’s CEO and installing Alexey Miller with a remit to secure the company’s assets. Browder even welcomed the 2003 arrest of Yukos Oil Co. boss Mikhail Khodorkovsky, seeing it as the beginning of the end for a small group of oligarchs that had stolen the country’s wealth. “I was cheering because I thought things were finally going to get back to normal,” he says. “One down, 21 to go.”

Reality finally hit home in November 2005, when Browder was detained at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport on his return from a weekend in London, held for 15 hours and thrown out of the country.

At this point Browder’s story of investing bravado turns into a thriller as compelling as any John le Carré spy novel. He succeeded in spiriting Hermitage’s then-$4.5 billion in capital out of Russia and moving his key staff to London, but he failed to anticipate the depravity of corrupt Interior Ministry officials. They fraudulently reregistered several Hermitage shell companies, reclaimed $230 million in taxes that Hermitage had paid and arrested Magnitsky on trumped-up charges of fraud. After a year of brutal treatment in Russia’s modern-day gulag, Magnitsky was beaten and left to die in an isolation cell.

“Everybody said you’re crazy to take on the oligarchs,” Browder recalls. “I took on the oligarchs, and everything was okay. And so I started to think that all this stuff was just prejudice and the reality was much less severe. And it turned out that everyone was right from the beginning: It was crazy to go to Russia, and it absolutely was crazy to take on the oligarchs. The consequences have been literally fatal.”

Browder tried to turn Hermitage into an emerging-markets fund, but in 2013 he returned investors’ money; today he runs the firm as a family office. His main obsession is bringing Magnitsky’s killers to justice. His passionate lobbying persuaded the U.S. Congress to pass the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012, which bars 34 people implicated in the lawyer’s murder from visiting the U.S. or using the country’s banking system. Last year the European Parliament passed a resolution calling for similar sanctions.

Browder’s perceived arrogance and high-profile tactics rankled many rivals in earlier years, but his efforts to expose corruption and track down Magnitsky’s killers have won him admiration. “He’s a hero,” says Ian Hague, co-founder of New York–based Firebird Management, another pioneer investor in post-Soviet Russia, which continues to manage some $400 million in assets there. “I don’t think there’s a single individual who’s had a bigger impact on Russia for the positive than him. Someday they’ll build a statue to him over there — when they come to their senses.”

Browder isn’t holding his breath for that. He worries about his own security, mindful of the murder by polonium poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko, a former officer of Russia’s FSB secret service, at a London hotel in 2006. In 2012, Alexander Perepilichnyy, a Russian exile who provided Browder’s team with information about the fraud against Hermitage, was found dead on a roadside near his home in the southwest London suburb of Weybridge. And in 2013, Russian authorities put Browder on trial in absentia — and Magnitsky posthumously — for tax evasion. They even tried to issue an international arrest warrant through Interpol — the Red Notice of the book’s title — only to be turned down.

Browder can’t see any change for the better in Russia while Putin is in power. The president’s penchant for doubling down rather than backing down means that repression at home and aggression abroad are likely to get worse, and Browder urges the West to draw a firm line in Ukraine and arm the Kiev government.

“Putin’s backed himself into a corner by stealing so much money that he’s afraid of his own people,” he says. “He started this war because his presidency was shaky. He saw what happened to the Ukrainian president and realized that the same thing could happen to him very easily.”

Any investors tempted to pick up Russian assets on the cheap should think twice, Browder warns. With the ruble continuing to fall, Moscow could impose capital controls and nationalize shaky companies before long. The economic sanctions imposed by the West on Russian companies promise to bring back the bad old days of corporate theft. “When the capital markets are closed for Russian companies, there’s no incentives for corporations to behave themselves,” Browder says. “This is what happened after 1998, and the same thing is going to happen now. Corporate governance will get a lot worse in Russia because Western investors don’t matter anymore.”

That’s all right for Browder. Russia’s market doesn’t matter anymore to him. He has all his money in North America and Europe these days, though managing those funds takes second fiddle to his new career as a human rights campaigner.

“I think it’s more interesting to fight for justice than to fight for money,” he says.