The present economic environment is serving up an expanded set of concerns for Federal Reserve officials that may end up influencing policy in a manner that delays rate normalization. In fact, the recently released September 2014 Federal Open Market Committee minutes depict a central bank that appears less willing to normalize rates based on domestic economic considerations, as the comments mention slowing economic growth — particularly that of Europe — and a strong dollar as risks to the FOMC’s outlook. Of course, these concerns are prominent because in a globalized economy, financial market and trade interconnections can lead to domestic headwinds if our trade partners’ economies slow and our export sector becomes less competitive in the wake of dollar strength. Still, we think these concerns are being overplayed by the Fed.

Whereas markets have seen volatility increase in recent weeks, culminating in the extreme market gyrations of October 15, the excessive focus of many investors, in addition to their growing fears over global growth and an abundance of geopolitical risks, is on news events that ultimately hold only minimal long-term influence. Clearly, the direction of policy change is important for understanding how markets evolve, but it too should not be taken as the sole determinant of economic and financial market prospects. Indeed, there are several favorable secular factors at play in the U.S. economy today that are likely to hold an outsize impact on growth prospects and market dynamics in the decade ahead. They include latent corporate capital expenditure, advances in technology, the energy revolution, relatively positive demographics and the stabilization of the housing market. Further, in our view, these secular economic tailwinds now combine with the cyclical recovery in a manner that allows the U.S. growth trajectory to diverge from that of Europe, where fewer secular and cyclical advantages are present.

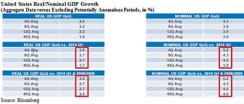

A careful examination of U.S. economic data helps illustrate this point. Over the past year virtually all measures of labor market slack have improved meaningfully and, apart from August’s weak nonfarm payroll print (a historically slow period for hiring), jobs gains have accelerated to healthy levels. In fact, with prior three-month, six-month and 12-month average nonfarm payroll gains of 224,000, 245,000 and 220,000, respectively, the current run rate in job creation is even a bit stronger than was typical of past periods of economic expansion. That is not surprising, as the economy is stronger than many have been willing to admit. Indeed, U.S. real GDP is running at 3.6 percent over the past four quarters, excluding the first quarter of 2014, with the impact of unusually harsh winter weather (see chart). Furthermore, the latest real GDP print came in at 4.6 percent, and we are expecting the third quarter to run around 3 percent — this is solid growth. That is particularly the case when looking at the past decade of average real GDP growth, which comes in at a surprisingly low 1.6 percent.

As a result, we at BlackRock continue to think that maintaining monetary policy accommodation at so-called emergency levels appears both unnecessary and potentially disruptive to the proper functioning of financial markets. And although we still think that it is plausible that the Fed will begin raising policy rate levels by the end of the first quarter of 2015, which would be earlier than markets are anticipating, recent meeting minutes and policymaker comments appear to make a later lift-off increasingly likely. We are not convinced that domestic economic evidence warrants such a delay, however. Indeed, even broader measures of economic slack, such as the U-6 unemployment rate, have begun to improve at a more rapid pace in the past year. Additionally, we would point to the data from the Labor Department’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, which shows that there were nearly 4.84 million job openings at the end of August, the highest level of this measure in more than a dozen years.

Finally, whereas some suggest that the Fed is waiting for the broad lack in wage increases to ease before returning to a more normal policy regime, even here some evidence displays improvement. Since the beginning of 2013, wage increases have turned sharply higher for the private industrial workers of some metropolitan regions (such as Dallas–Fort Worth and the San Francisco Bay Area area). Further, highly skilled and educated workers continue to see solid wage gains, so what is lost in the aggregation of data is that labor markets have become highly bifurcated (or fragmented) and that the average wage level has seemed stuck as many workers’ wages have merely kept pace with inflation. Corporate survey data also suggest that some improvement is likely on the way, and such a dynamic would imply to us that structural labor market factors are at play that are beyond monetary policy remedy.

We think, in contrast to the U.S., Europe is struggling with very weak levels of aggregate demand, fewer favorable economic catalysts and more negatives — including an essentially inoperative fiscal channel. Reacting to economic weakness and very low inflation, European Central Bank president Mario Draghi has announced plans to expand the central bank’s balance sheet via a set of asset purchase programs, although to date this hasn’t included the outright purchase of sovereign debt. Thus the current path of monetary policy accommodation implies (rightly) a divergence based on the varying economic prospects of the two regions, which, as we at BlackRock will cover in our next article, is mirrored in relative currency valuations as well.

The data clearly show that the U.S. is much further along, both in overall economic healing and in the monetary policy cycle, than is Europe, which has chronically lagged in its response to the financial crisis and ensuing recession. We think the fact that the euro zone is at risk of entering its third recession since 2008 is testimony to that fact. If one looks at U.S. and euro zone industrial production figures, the former has seen steadily improved gains since industrial production bottomed in 2009, and the U.S. has more than recovered its 2008 peak in that metric. Meanwhile, the euro zone saw its industrial production recovery off its 2009 bottom fail in 2011, and it has since declined even further. Moreover, key economic vital signs for Europe — purchasing managers’ index data, consumer price index data and capital investment data — have all recently turned down. And euro zone leverage levels and demographic characteristics are considerably less favorable when compared with those of the U.S.

This economic backdrop clearly holds implications for both U.S. dollar and euro valuations, but we do not think it places the U.S. recovery at risk. Therefore, Fed policymakers would do well to turn their attention to more immediate concerns, such as keeping the housing market recovery on track and ensuring that financial market conditions remain stable, rather than worrying about a modest slowing in global growth that is unlikely to derail the U.S. on its path of recovery.

Rick Rieder, managing director, is chief investment officer of fundamental fixed income and co-head of Americas fixed income for BlackRock in New York.

Get more on macro.