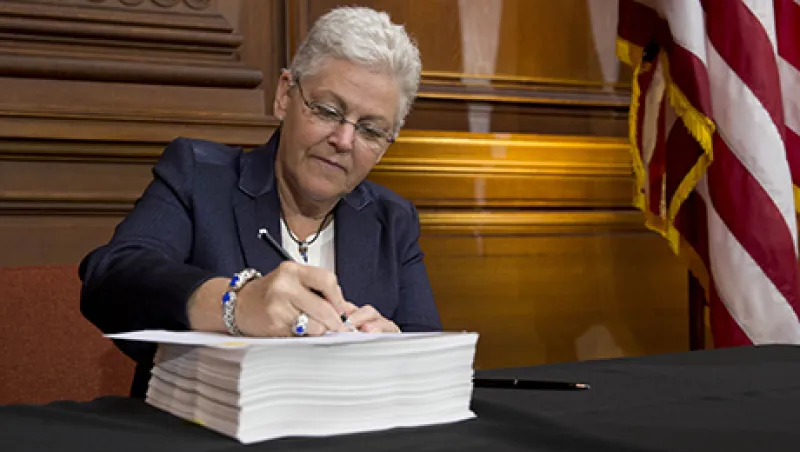

Gina McCarthy, administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), signs a power plant regulation proposal during a news conference in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Monday, June 2, 2014. President Barack Obama is proposing cuts in greenhouse-gas emissions from the nation's power plants by an average of 30 percent from 2005 levels, a key part of his plan to fight climate change that also carries political risks. The proposal, issued today by the EPA, represents the boldest steps the U.S. has taken to fight global warming. Photographer: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg *** Local Caption *** Gina McCarthy

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg