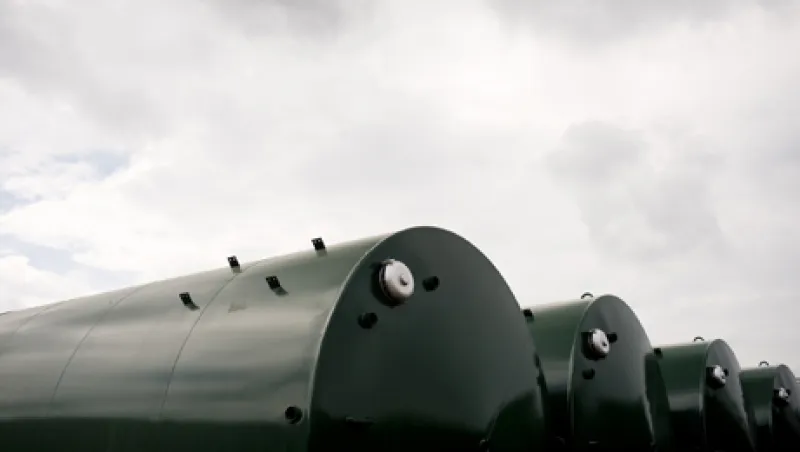

Oil tanks lie on their sides awaiting delivery Westerman Companies Inc., a company that manufactures oil tanks for the fracking industry in Bremen, Ohio, U.S. on Tuesday, Sept. 4, 2012. A boom in oil production from the shale formations of North Dakota and Texas has the U.S. on a course to cut its reliance on imported crude oil to about 42 percent this year, the lowest level in two decades. Photographer: Ty Wright/Bloomberg

Ty Wright/Bloomberg