Film directors used to pull their villains, good guys and drama from bloody coups, historical battlefields and the fantasy worlds of comic books. But since the financial crisis, they’ve increasingly been turning to sinking banks, corrupt hedge funds and king-making stockholders. That’s the territory plowed by Costa-Gavras’ latest feature, Capital, which opened in the U.S. late last month. Costa-Gavras, whose 22 films include Z, an account of the 1967 overthrow of the Greek government that won an Oscar for best foreign language picture in 1969, says he looks for ways to address universal themes like law and justice, oppression, violence and torture. The Greek-French director’s 1982 Missing, starring Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek, is about a U.S. journalist who disappeared in Chile after the country’s 1973 military coup.

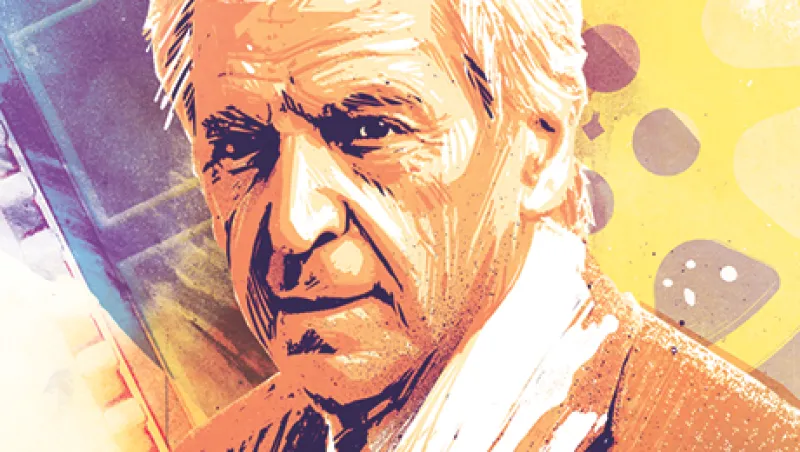

Costa-Gavras, 80, became intrigued by the unwritten rules of international finance after reading French author Stéphane Osmont’s 2004 novel Le capital. His script for Capital, based on the book, centers on Marc Tourneuil (Gad Elmaleh), the power-hungry CEO of France’s Phenix Bank, who finds himself in the middle of a dangerous battle among management, shareholders and a U.S. hedge fund.

Although Costa-Gavras may not succeed in making his point clear, the contrast he makes between French capitalism and the U.S. version is plain: The greedy French seem tempered by labor unions and family ties, while the Americans are unapologetic market cowboys. Senior Writer Julie Segal recently talked to the veteran director at the Mercer hotel in New York’s SoHo neighborhood.

Tell us what prompted you to make this movie.

I wanted to make a movie about money and how money affects a society and people. How it becomes a religion. Then I discovered this book by Osmont, who was a financier for years. Most of the book came from his own experience. But I knew I would change the ending, which punished its wrongdoers. This was during the period of the Lehman Brothers catastrophe, when so many people lost money and yet no one went to jail. So my movie couldn’t have that resolute ending. The other thing that motivated me is that during my research I met with bankers, many of whom I already knew and some whom I only recently met, and they all knew about the problems with finance and what solutions could be put in place. But all were practicing something different as business leaders. Their vision didn’t match how they actually operated.

I was also inspired by [Le capitalisme total,] a book written by [former Crédit Lyonnais chairman Jean Peyrelevade]. He says that democracies get taken over by business. The people we elect don’t have power. Democracy is a kind of placebo; it has no effect.

What surprised you the most in your research?

That these public enterprises really belong to the stock-holders and they do what stockholders want. If a senior manager wants to stay king, then he or she needs to make the kingmakers happy. I was fascinated with that.

Have you thought about any solutions?

I’m a filmmaker. Filmmakers don’t have solutions. But that said, there needs to be more regulation. And even though lawmakers seem to have spent a lot of time crafting rules, the people I speak to say there have been few real changes. The French, for example, say, “If we regulate ourselves, the Americans won’t regulate and they will eat us completely.” Capitalism is a system that has to be regulated; otherwise capitalism is stronger than democracy.

During one scene in the movie, CEO Tourneuil becomes livid with an old couple, calling pensioners slave drivers. He goes on to talk about pensioners, the majority of stockholders, pushing companies to the brink and leading them to make unethical decisions.

Yes, in Europe it’s a drama between young and old. In Spain, Portugal, Greece and so on, there is 30 to 40 percent unemployment among young people. There is no future for them; they instead want to escape to another country to work. But it all depends on money and who has the money. Do banks use their money to please the shareholders or to help enterprises make goods for everybody and create new jobs? It’s a battle between pensioners and young people.

Did you learn things about money that you didn’t know before?

When I started doing movies, we talked about doing good movies, not what would sell. We didn’t need to drive a Ferrari; we needed a small, efficient car to get us from one place to another. Twenty-five, 30 years later, it’s about money. If you have money, you are respected; if you don’t have money, you are not respected. My film’s CEO is obsessed with that respect, and that direction is very negative. No one is innocent. When you listen to the unions, they speak about money, not creating a better society. Young people want to go to university to study money and get rich in finance. It’s a global problem.

Read more about hedge funds.