Institutional investors are creating expensive but ineffective portfolios, according to an extensive analysis by Northern Trust Asset Management of more than 200 client and prospects’ equity portfolios.

Over four years of examination, NTAM found, among other things, that investors had almost twice as much uncompensated risk, such as currency or large sector bets, as risk for which they were actually paid. Compensated risks include styles, such as value or growth, and stock selection. Clients also commonly held so many stocks that they cancelled one another out, invalidating the case for active management.

The volume of uncompensated risks was a “startling discovery,” said Michael Hunstad, head of quantitative strategies at NTAM. Uncompensated risks washed out about 50 percent of all the active risks that investors were taking in the studied portfolios. That means investors paid about twice as much for each basis point of active risk as intended, according to the report.

“When we learn how to invest, we’re taught two rules of thumb. The first one is if you want more return you have to take more risk. The second is don’t put all your eggs in one basket — or diversify,” Hunstad said in an interview with Institutional Investor. “This report shows that people learned the lessons, but haven’t applied them well. They want to diversify, but they’re diversifying away the very thing they want, which is excess return.”

An institution might think that two managers diversify its stock exposures. But they often don’t. Say one is overweight Microsoft and one is underweight Microsoft: together they charge active management fees for market-cap weighted exposure.

“This is an extreme example,” Hunstad said, “but we’ve seen instances where portfolios hold both the Russell 1000 Value and Russell 1000 Growth index. But they equal the Russell 1000 index. “That’s like breaking the chocolate bar in half, and selling each for a higher price than the whole.”

Hunstad said that investors haven’t taken advantage of sophisticated tools and data developed in recent years to decompose various forms of risk, such as country, region, and idiosyncratic risks.

“When you walk up to the salad bar, there are all these ingredients. Do you want a little bit of everything? Probably not. That’s the cap-weighted benchmark,” said NTAM’s quant chief. “That’s what we face today. I have this salad bar of risks that I can take. You used to get a salad or not. Now you have so many different combinations to choose from.”

The risk report grew out of NTAM’s portfolio analysis service, which aims to identify hidden risks and the reasons why institutions fall short of their objectives.

[II Deep Dive: When Diversification Does More Harm Than Good]

According to the study, the so-called cancellation effect weighs down institutions’ equity books.

“These portfolios generally contained a diversified group of managers that, when combined, resulted in a portfolio that mimicked the benchmark, but with a higher fee,” according to the report. “One of the leading causes of the performance-hindering cancellation effect, were portfolios that showed signs of being built around the conventional ‘style box.’ And while many investors may not admit to using this approach, our research uncovered that it was still quite common,” according to the report.

Hunstad said international investors are less guilty of using the method. “It’s fascinating when you do this for clients outside the U.S. There is almost no evidence of the style box,” he said.

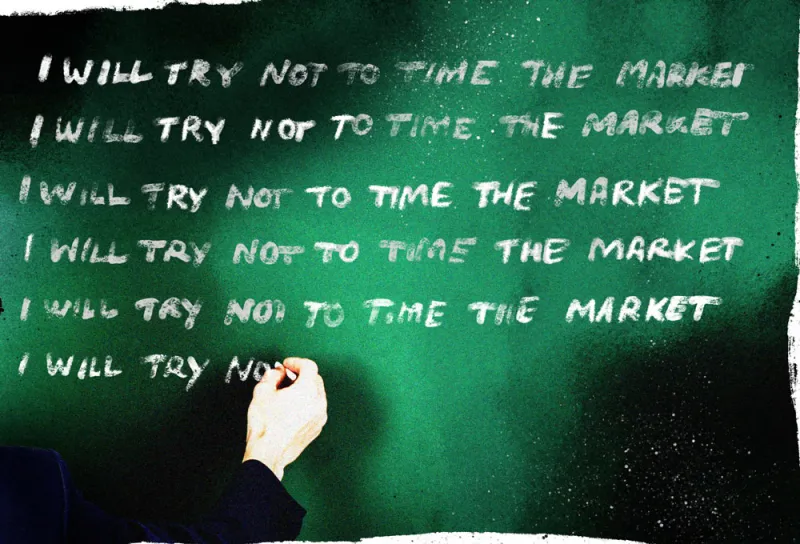

The report also found that market timing was a common and costly sin for institutions. In the years when a high percentage of active managers outperformed, institutions raised their allocations to active. When few active managers beat benchmarks, institutions cut their exposure.

This is a damaging exercise, Hunstad pointed out. He cited an academic study published in July that found past performance and personal connections were the two biggest factors allocators use in determining which asset managers to ultimately hire. A manager that moved from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile in performance increased the probability of the firm being hired by about 30 percent. But once hired, these managers generated significantly lower returns than their peers in the following three years.

“The dynamics of the market are changing so much. What appears to be skill is often luck and that luck tends to be short lived,” Hunstad said.