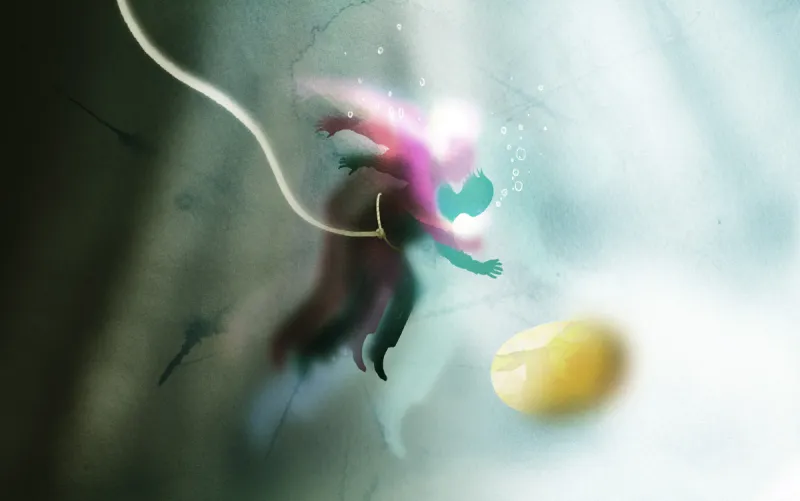

Illustration by II

At 12:00 p.m. on Friday, March 13th, less than a week after I submitted my notice to leave a job at the Texas Municipal Retirement System, our CIO called us around a conference table to deliver some news.

As a result of the then rapidly spreading coronavirus, he said, TMRS would immediately close its doors to all non-essential workers.

The investment team would be working from home indefinitely.

And just like that, I had a half-day to pack up my personal effects and say goodbye. It wasn’t my last day on the job, but it would be my last day in the office. The reality that I would be leaving the security of a government job — and all the benefits that entails — in an increasingly uncertain time suddenly became very real.

As a father of three, I wondered if giving up that stable job, excellent health benefits (now, of all times), and a secure retirement package to bet on myself was such a great idea. In an entrepreneurial setting, I won’t have a lot of the advantages I’ve had previously — but I won’t have any of the substantial challenges, either.

It’s a trade I’m happy to make.

To be clear, I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunities that I’ve had in my roles at public pensions. Along the way, I’ve worked with some great people and gotten to meet some of the best investors in the world while allocating billions of dollars across alternatives — generating decent returns, I might add! — all to help advance a social good, namely helping to secure the retirements of hundreds of thousands of public servants. The fact that my mother is a retired educator made this objective very real and personal. It would be hard to imagine accumulating a similar amount of responsibility and experience as quickly in the private sector.

However, life in the public sector can also be frustrating — extremely frustrating.

Without fully understanding it, many institutions have put enormous — and arbitrary — obstacles in the way of their own investment success. It often felt like I was trying to swim a race against Michael Phelps with an anchor tied around my waist.

Sure, some U.S. public pensions have evolved to become very efficient, very well-run commercial investment enterprises — because they understand what they are. Typically, 65 to 80 percent of the value of retirement benefits paid out by public pensions comes from investment gains. Any enterprise is what it actually does, not what it promises to do. Making a promise to provide a paycheck in the future creates a liability. How you fulfill that promise is what you are, and for a pension fund, investing is how it does that.

Make no mistake: A pension fund is an investment firm. A nonprofit public one, yes, but investing is the core competency of the institution — or, more correctly, it must be if it is to remain solvent in the long run.

Unfortunately, many plans are still stuck in the mindset of being purely government agencies. They believe they are the boss. A hierarchical command-and-control architecture dictates that paperwork has to be filled out a certain way, specific boxes need to be checked (without exception!), committees need to be convened, and the right people have to sign off on everything. That can be up to seven different people for a single investment, none of whom may have any investment experience.

All of which takes time — lots of time — and effort, frequently to the detriment of actual investment work. Listen, of course process matters, but real process. Not busywork. Filling out paperwork and getting through internal processes are the only things that matter when you apply for a driver’s license. But forms and rubber stamps don’t add value to investment decision–making.

A good analogy is that of a lifeguard. Let’s assume there are only two functions lifeguards can perform — filling out a detailed time sheet in 15-minute increments and scanning the waterfront. The reality is that they aren’t actually doing their job if they spend all day on time sheets. You want those lifeguards watching swimmers as much as possible.

Public pension investment professionals spend too much time and effort fighting to do their jobs. Internal bureaucracy probably took up 25 percent of the total work hours of my small team.

And it’s not about being lazy or unwilling to work hard. Consider, for example, an in-demand fund that had been in process for some time and finally created capacity — but required one month for work to be finished up before closing. Every week needed for internal paperwork, presentations, and hoop-jumping, well, that meant one less week of actual due diligence and investment debate. Or maybe we would have just passed on the manager, which is also suboptimal as it’s often the best-performing managers that require the most flexible processes.

This is counterproductive. And that’s not just an opinion. Research shows that the impact of due diligence in alternatives is meaningful for returns. Spending more hours doing actual research before making a decision results in higher returns, and the effect is more pronounced the greater the dispersion of returns. The act of getting that decision approved shouldn’t consume so much of a limited staff’s time.

Hierarchical governance is certainly not ideal for any investment strategy, but it may be less deleterious for a simple 60/40 public market approach. In this portfolio, dispersion of returns is far lower and execution is less manual and labor-intensive. And once a strategic decision is made, doing nothing is often the best thing. (It also is cheaper and requires a far smaller investment staff, which are certainly appropriate considerations for institutions.)

However, if a public pension has made the decision to move into alternatives, a bureaucratic governance structure is particularly harmful. The difference between top and bottom managers in private equity is ten times as wide as it is in public equity. Regardless, loads of academic research shows that pensions where board trustees retain manager selection underperform those funds that have delegated discretion to a qualified staff instead (see here, here, and here for examples).

You see, this is a knowledge-based industry; it is a technical profession. And there is research on what works and what doesn’t. There are in fact best practices, or at least unequivocally better ones. And many pensions need to hear the research, even if the conversation is an uncomfortable one for those entrenched in the authority of the bureaucracy.

This requires intentionally designing governance and management, from authority to processes to execution and staffing. And that last part is critical. If you don’t have the right people for your processes, or processes for your people, you run the risk of failure.

We all know what happens when a sports franchise hires a coach with a certain philosophy but has a general manager who completely ignores that when recruiting players. Dynasties like the New England Patriots and the San Antonio Spurs have done the exact opposite for decades, empowering their coaches with personnel decisions, and we know the results.

No hospital would put a tax lawyer in charge of operating room procedures, dismissing the professional recommendations of the neurosurgeons as self-serving. That could perversely create massive liability.

No town hires a fire chief but prevents him from fighting a fire until a council comprising the mayor, an accountant from the budgetary office, a judge, and the school superintendent can convene and approve his recommendations. That’s what standard operating procedures are for!

Then why are we still investing nearly $5 trillion of state and local pension money, often heavily allocated to alternatives, in this way?

This old governance structure doesn’t work in investing, which is why private sector investment firms — and truthfully, most public pensions outside of the States — don’t operate this way anymore. Markets don’t care who you are, or if you are the government. They operate according to their own time frame. You see, Mr. Market is the boss, not any of us.

Success in investing requires understanding that markets are like the ocean: neither good nor bad, but powerful and inexorable. If you refuse to yield to the authority of the waves and try to fight them, you will surely get smashed on the rocks, left battered and bruised.

It is only when you submit to the power of the waves that you can successfully ride them and let them take you wherever they are going. The trick is to figure out their cadence and direction. Of course, that’s no easy thing, but you first must accept it is not about power, authority, or any of that. It’s about humility, accountability, and performance — pretty much the antithesis of a government bureaucracy.

The markets will set your deadlines for you, whether you like it or not. And performance will dictate the efficacy of your governance. This is a challenge for the government mentality. Process is what drives performance, but performance ultimately determines if the process works or not. If it’s not working, the process has to change. Even if it is working, it can probably get better.

Finally, performance-linked compensation is also a critical component of aligning interests and owning outcomes. The higher dispersion of returns in alternatives means a higher probability of both good and bad outcomes. And more due diligence is the only means of consistently differentiating between the two.

Now investment professionals realize they already bear the downside risk of a manager recommendation. They are experienced enough to understand the consequences of hiring a hedge fund that blows up or allocating to a private equity fund that winds up with fraud in it.

Turns out you actually can be fired, and possibly sued.

Perhaps that’s why the vast majority of the instances of malfeasance and pay-to-play in our industry have been not from investment staff, but rather from trustees and executive directors. They don’t know what they don’t know.

Though variable compensation may well be self-serving, not having it in place for alternatives creates a huge, warped incentive. Why would people choose to work 20 or 30 more hours every week than they have to? Particularly if they’re not getting compensated for it and have the career risk of wider dispersion of returns?

The answer: They probably won’t for long.

They may stop doing so much work and just start picking managers based on less research, effectively shooting from the hip. Or they may just start hiring bigger, safer managers with lower dispersion of returns. As the saying goes, you never get fired for hiring IBM. Plus, they can cut their workload in half. The problem is, most research shows that returns go down substantially when that compromise is made.

Or, if they don’t want to make that compromise, often they’ll leave.

I know that I will probably be working longer hours now than I was in the past. But doing less was never the goal. Back to my earlier lifeguard analogy: I will get to spend much more of my time watching the water. Not only is that the best part of the job, but it’s what drives performance, particularly in alternatives.

And it is also motivating to feel some sense of control again. Of course, I can be fired if I underperform, but I always could have been. Now clients can leave if we don’t do our job, and I know raising assets is no easy task to begin with, which does make the risk of failure more real.

But I do get to be involved directly in the final decision on investments and have a significant impact on processes across the firm. And process drives outcome. This means I can also do better for my family financially if I generate more value for the firm and ultimately for our clients.

Instead of being based on an arbitrary rule, compensation will now be largely determined by the quality of my work and the opinion of the real boss, Mr. Market. And I will finally get some of the upside if our investments outperform. Yes, it is undeniably self-serving, but none of us works for free. And I have some power over my destiny again.

The chance to remove bureaucratic elements of the investment process, to learn and innovate across alternatives and go where opportunities exist while aligning interests and outcomes for myself, my firm, and my clients is exciting. I can achieve what my firm and my clients believe I am capable of, rather than what a bureaucracy allows me to.

If I fail, I fail. But if I get it right, if we can in fact harness the power of the waves — or wind, as the case may be — to generate superior returns for our clients, then we will all do better.

And that’s precisely why I am still far more excited than nervous. That’s a bet I’m willing to make.

I’m also looking forward to not having to fill out a time sheet anymore.