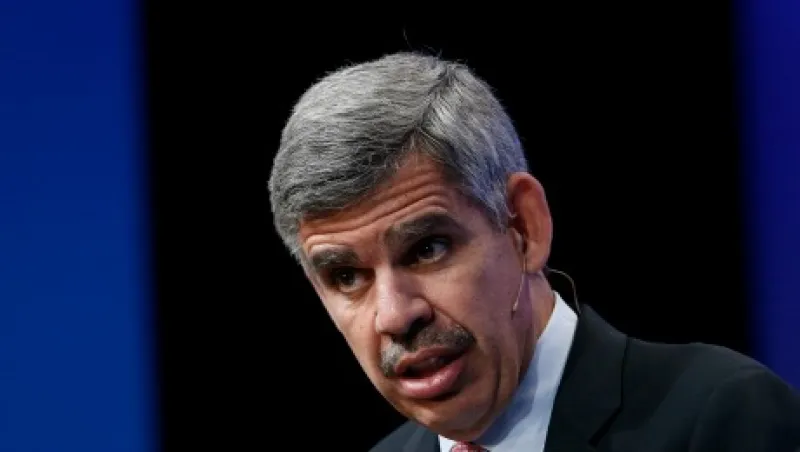

Despite several years of vigorous easing, the central banks of the euro zone, Japan and even the U.S. haven’t been able spark stellar economic growth, leaving them stuck in a liquidity trap, says Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at Munich–based insurer and asset manager Allianz.

The problem is that central banks can’t do the job by themselves, he told Institutional Investor in an e-mail interview. Fiscal and regulatory policy must pull their weight too. “All three central banks face the same basic challenge,” he says. “They find themselves still having to pursue broad macroeconomic objectives with partial and imperfect tools — and not out of choice but out of necessity.”

As for the economies, the euro zone grew only 1.2 percent annualized in the third quarter, Japan shrank 0.8 percent, and the U.S. expanded 1.5 percent.

“The euro zone and Japan are in a better economic place than a year ago, but they are yet to fully overcome significant downside risk, let alone establish the basis for high, sustained and inclusive growth,” he writes.

In the U.S. “economic healing continues with notable and consistent gains in job creation,” El-Erian notes. “But the economy has yet to attain the escape velocity that it is capable of and should be achieving.” So the U.S. is stuck with growth of 2 to 2.5 percent. “And the longer this low-growth equilibrium persists, the greater the threat that it could also drag down potential growth,” El-Erian says.

On the monetary policy front, the Fed has kept the federal funds rate at a record low since December 2008, though it appears poised to begin raising rates next month. The European Central Bank is buying 60 billion euros’ ($64 billion) worth of bonds a month and making noise about easing further. The Bank of Japan is engaged in up to 12 trillion yen ($97.2 billion) in quantitative easing a month, and there is speculation that it too may open the liquidity spigot further.

But the central banks can’t go it alone, El-Erian says. “All three desperately need other policymaking entities, with tools much better suited for the task at hand, to join them in formulating a comprehensive policy effort.” More effective global policy coordination also would help. “They have been waiting for this for quite a while,” he says. “And, given the realities of domestic politics, it looks like they will have to continue to wait.”

The Fed, of course, ended its quantitative easing program last year, and El-Erian sees a better than 50 percent chance that the U.S. central bank will boost rates next month. “Of the three, the Fed is closest to exiting the prolonged reliance on unconventional policies and thus continuing to gradually normalize monetary policy,” he says.

“Part of that reflects the steady healing of the economy and the robust creation of jobs, both of which have been helped by the more entrepreneurial nature of the U.S. economy and significant innovations,” he says. The unemployment rate dropped to a seven-year low of 5 percent in October.

Ethan Harris, co-head of global economic research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch in New York, says the Fed deserves a lot of credit for buoying the economy. The Fed acted to heal an economy coming out of the worst banking and real estate crisis in postwar history while fighting massive headwinds in Washington — fiscal austerity and dysfunction, he says. “The economy is much more resilient than three to five years ago and should be able to pick up speed on its own. The Fed has put us on the cusp of real wage and price inflation.”

El-Erian says a Fed rate hike in December would reflect not just a strengthening economy but also “what seems to be a rising (and, in my view, legitimate) concern among Fed officials about the unintended consequences of unconventional policies, including the growing risk of financial instability down the road.”

Meanwhile, monetary accommodation has proved to be an elixir for U.S. stocks and bonds over the past six and a half years. “Viewing central banks as their BFFs [best friends forever], both markets have been bolstered by massive monetary injections,” El-Erian says. “In the process, quite a few market prices have decoupled from fundamentals.”

The best-case scenario is that improving fundamentals will eventually validate the elevated asset prices and push them even higher, El-Erian says. “But the concern is that fundamentals will continue to fall short of escape velocity. If this persists for long, financial markets would converge down to fundamentals. And, given patchy liquidity, they could overshoot on the way down.”