Efficient Frontier Models: Dangerous Toys

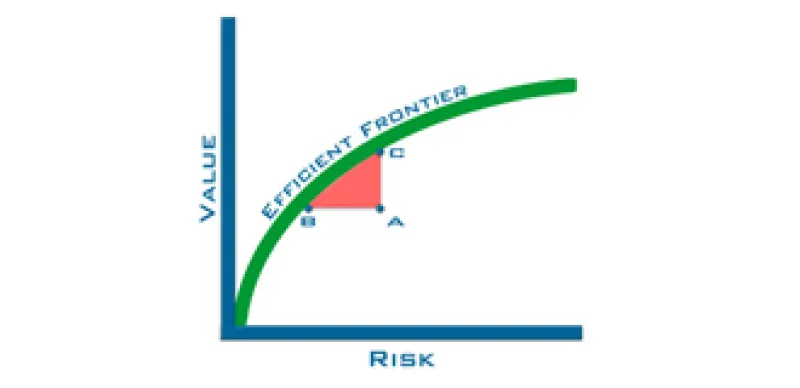

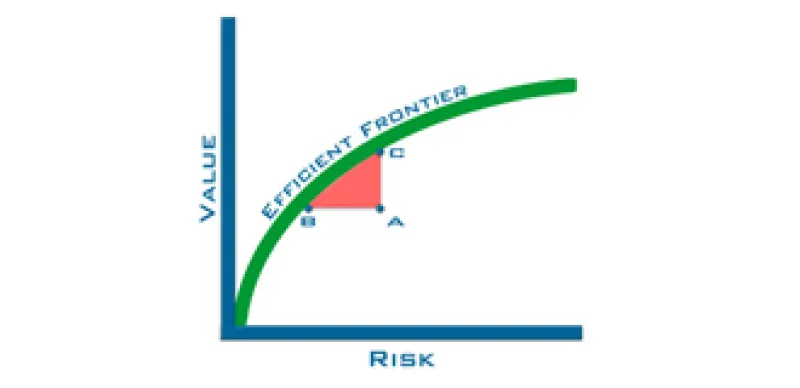

When it comes to asset allocation, efficient-frontier models suffer from a few shortcomings.

Larry Swedroe and David Ressner

October 23, 2009