IN JULY 2011 THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development decided to expand the institution’s theater of operations into what it called the Southern Mediterranean: Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia. The move was a dramatic departure for a bank created to foster the growth of market-oriented economies in the former Communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the old Soviet Union. But having largely fulfilled its purpose in many of those countries, the London-based bank was in need of a new mission. Helping countries jolted by the Arab Spring make the transition from authoritarian regimes to prosperous and pluralistic societies seemed like a natural undertaking. Executives suggested that the bank could lend and invest as much as €2.5 billion ($3.2 billion) a year in the Semed, as the European Union terms the region.

Nearly two years later the EBRD has yet to open an office in Cairo, the epicenter of Mideast revolution. The reason? Egypt’s government has not granted the necessary permission. “We are not stuck over any particular issue,” says Hans Peter Lankes, the bank’s head of institutional strategy. “It’s just that in the government there is a lot of uncertainty and shifting competencies.”

The bank’s odyssey through the Egyptian bureaucracy highlights a broader challenge for Europe: How can it nurture the shoots of liberty in its North African neighbors when those neighbors, particularly Egypt, do little to cooperate?

The EBRD is just one institution that is currently coming up well short of its grand intentions. At a summit meeting in Deauville, France, in May 2011, the Group of Eight nations promised to provide up to $38 billion in aid and investment to the four Southern Mediterranean countries as well as Lebanon and Syria. So far, a small fraction of that sum has been spent.

Philippe Maystadt, then president of the European Investment Bank, declared that his organization could lend €6 billion “to support democratic transition” in the region by the end of 2013. The actual total for 2012 was €1.68 billion, of which €1 billion went to Morocco. European officials speak warmly of Moroccan King Mohammed VI’s “change from within” since neighboring authoritarian rulers were swept away, but it’s striking that the lion’s share of the EIB’s investments, which are meant to buttress the move toward democracy, has gone to one of the region’s entrenched monarchies.

The International Monetary Fund has offered to lend Egypt $4.8 billion in assistance for some time, but President Mohamed Morsi and his Muslim Brotherhood–led government have balked at the conditions, which include slashing popular subsidies for food and fuel. The latest IMF talks, last month, proved fruitless, and Egyptian analysts see little reason to believe that Morsi will agree to an assistance package before parliamentary elections that are expected to be held this autumn. “If they raise the prices of bread and diesel before the election, they are afraid they might lose,” says Magdi Sobhi, senior economist at the al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo. “They may find the courage, but I doubt it.”

Egypt could certainly use the IMF’s money. Economic growth has slowed from 5.1 percent in the prerevolutionary year of 2010 to 2 percent last year, barely keeping pace with the country’s population growth. Foreign currency reserves have dropped by more than half since former president Hosni Mubarak resigned in the face of mass protests in February 2011. Reserves have hovered around $13 billion for most of this year, or slightly below three months of imports, a level typically regarded as critical. Central bank measures to restrict currency trading have spurred the growth of a black market in dollars and euros, pushing real inflation for many imported goods well into double digits, Sobhi says. The government’s budget deficit is running at about 12 percent of gross domestic product.

Yet the stalemate between Egypt and its would-be benefactors in the West persists. Officials at international financial institutions in Brussels, London and Washington — where the World Bank Group’s private sector lending arm, International Finance Corp., has been the most prolific multilateral investor in the Arab world — hunt for projects that would allow them to sidestep Cairo’s political morass and directly spur private enterprise. In March the EBRD did its first Egyptian deal by lending $24.3 million to Universal Metallurgical Co. to finish the construction of a washing-machine factory. Last year IFC loaned $33.5 million to TransGlobe Energy Corp., a Calgary, Alberta–based natural-gas company whose assets are concentrated in Egypt, and $11 million to industrial-fiber maker Nile Kordsa Co.

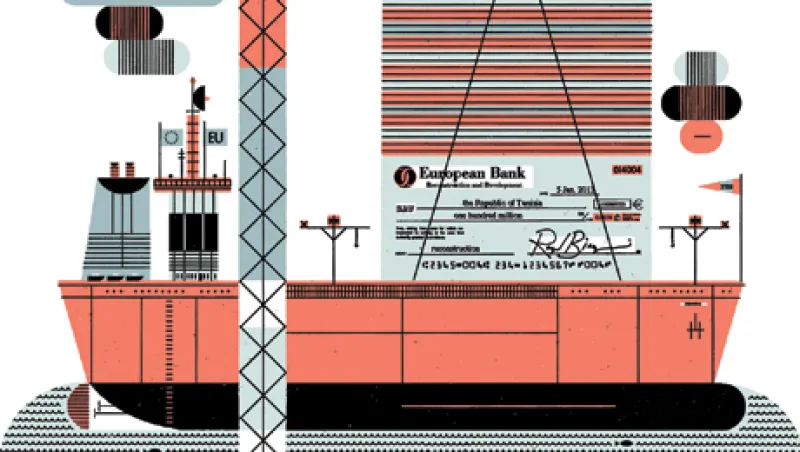

Officials at the various lending agencies are optimistic about the prospect for investments in Tunisia, which last month reached a tentative agreement with the IMF on a $1.75 billion assistance package. Such deals would have symbolic as well as practical value considering that the country gave birth to the Arab Spring when a fruit vendor burned himself to death in December 2010 to protest bureaucratic obstacles, unleashing a wave of demonstrations across the region. Tunisia is small, however. It has a population of 10.8 million, barely one eighth that of Egypt’s 83 million, and a modest GDP of $104 billion, less than one fifth of Egypt’s $535 billion, according to The CIA World Factbook.

Egypt’s size and centrality to the Arab world make the outcome of its revolution pivotal to the wider region. For that reason, Western lending institutions express frustration at the pace of change as well as their ability to operate in the country. “I wouldn’t say that we were naive, exactly,” says Marcus Cornaro, a deputy director at EuropeAid, the European Commission’s assistance arm. “But it was a mistake to assume that much could be done very quickly.”

THE U.S. HAS FUNDED EGYPT’S MILITARY for decades, but economically the country is firmly within Europe’s sphere of influence. The EU is by far Egypt’s largest trading partner, accounting for 30 percent of all imports and exports in 2011. It supplies 75 percent of the country’s direct foreign investment.

European authorities were quick to grasp the historic significance of the Arab Spring and seek to support the region’s political and economic transformation. “The magnitude of this challenge is beyond anything since the Berlin Wall, and Europe must rise to it,” says Michael Mann, a spokesman for Catherine Ashton, the EU’s high representative for foreign affairs.

Western Europe was a different place when Communism collapsed two decades ago, though. The region was flush from the prosperity of the 1980s and infused with confidence by the sudden, bloodless reunification of Germany. The enthusiasm reached a high point in 1992, when the European Economic Community, as the 12-member bloc was then known, agreed to launch a single currency by the end of the decade.

In 2011, by contrast, the EU was still reeling from the 2008 global financial meltdown, which set off a debt crisis in the union’s periphery that threatened to break up the euro. Against that background Ashton and EU leaders left much of the financial challenge of assisting the Arab world to two development banks: the European Investment Bank, a Luxembourg-based EU agency that extended $52.2 billion in credits last year, $7.4 billion of them outside the EU, and the EBRD, a multilateral lender owned by 62 governments around the world.

It took some adroit diplomacy by Ashton to harness the EBRD’s resources to the Arab cause. In March 2011 she proposed a “partnership for democracy and prosperity” that would give the bank a role in the Southern Mediterranean. The plan enshrined a principle of “more for more”: Europe and its associated agencies would open their wallets wider as the region moved closer to the EU’s political and economic ideals. So far, results in Egypt might better be described as less for less.

“Twenty years ago Eastern Europe had a clear direction, rejecting the socialist model and moving toward a market economy,” says the EBRD’s Lankes. Today, he adds, “in North Africa some of the excesses of the old regime are associated with market economies. Markets need to be reinvented.”

Another key difference is that Egypt, unlike the former Eastern bloc, has an alternative funding source in the richer Arab countries. This is a mixed blessing from the European standpoint, as largesse from Gulf states can help Morsi put off the painful yet essential reforms that would be required for Western assistance. In early April, when the most recent IMF delegation was visiting Cairo, Libya and Qatar announced a $5 billion transfer to the Egyptian Treasury — probably enough to tide the government over through the autumn parliamentary elections. As a result, talks with the IMF duly bogged down. Saudi Arabia has provided more than $1 billion in assistance.

“The Gulf states keep Egypt on a drip,” says one European official. “But it’s very hard to understand what the conditions are for a Saudi or Qatari paycheck.”

The IMF is pressing Egypt to overhaul subsidy policies that the Fund regards as wasteful and inequitable. The central bone of contention: fuel subsidies that eat up about $18 billion a year, or more than 20 percent of the state budget. A recent World Bank study found that most of the benefit is reaped by the richest 20 percent of Egyptians, as they are the most likely to own cars. The IMF also wants to reform food subsidies, which technocrats say are so inefficient that Egyptian farmers feed cheap bread to their livestock.

Last month IMF managing director Christine Lagarde appealed to Cairo to return to the bargaining table, asserting that an aid-for-reform package would lift the Egyptian economy. “It is growing, but the growth numbers could be certainly a lot better if the situation was stable from the financial and economic point of view,” she said at the Fund’s spring meetings in Washington. European officials hope she succeeds. “We are integrating our assistance package with the IMF and World Bank,” says EuropeAid’s Cornaro. “An IMF package would be quite a breakthrough.”

THE EBRD IS HITTING INTERNAL snags as well in its southern expansion. Board approval for establishing a presence in the Southern Mediterranean countries was just the start of a process that requires ratification by all of the 62 states that fund the bank. For many that means a formal parliamentary process. The last time the EBRD expanded its remit, moving into Mongolia, the process took three years. Twenty-one months after the board’s announcement on Semed, five countries, including Mexico and Uzbekistan, had yet to sign off. (Israel, the EBRD member most directly concerned with the upheaval of the Arab Spring, ratified quickly and has fully supported the bank’s entry, Lankes says.)

EBRD managers haven’t been sitting idle, however. The board adopted a resolution at its May 2012 annual meeting that allows the bank to invest as much as €1 billion of its profits in the Semed countries. Since then the bank has committed some €450 million, about €400 million of which has gone to Jordan and Morocco.

IFC was already on the ground when the Arab Spring began, and it has mobilized faster. It has invested $723 million in 11 projects in Egypt since Mubarak’s fall. Mouayed Makhlouf, IFC’s director for Middle East and North Africa, is by far the most upbeat of the international specialists focused on the country. “One positive about the Arab Spring is that Egyptian companies need us a lot more now,” he explains. “The IFC has made a lot of money out of economies in transition. It is in our mandate to be countercyclical.”

The World Bank arm sees potential profit in all sectors of the Egyptian economy except tourism, which can rely on private investment, Makhlouf says. Aside from TransGlobe and Nile Kordsa, investments include $6 million in equity for Fawry, a technology start-up trying to develop an electronic payments system in Egypt, and a $15 million loan to Cairo Investment and Real Estate Development, which builds schools.

But more than half of IFC’s commitment to Egypt is devoted to a single company, Orascom Construction Industries, which has battled the Morsi government over taxes and is trying to shift its stock exchange listing from Cairo to Amsterdam (see story, page 38). And Makhlouf’s optimism goes only so far. “The situation is very challenging,” he says. “It is very hard to say that businesspeople are excited or see opportunities in the current conditions.”

The biggest recipients of Western aid are the Arab dominoes that did not fall: the hereditary monarchs still on their thrones in Jordan and Morocco. The EBRD’s largest investment in Semed to date is a $100 million commitment to a power plant in Jordan. “A project like this involves offtake arrangements for many years in the future, and that requires faith in the stability of the regulatory regime,” says the bank’s Lankes.

IFC is also bullish on Jordan. Makhlouf extols the beauty of Amman’s Queen Alia International Airport, which opened in March after $120 million in financing from the Washington-based multilateral. IFC’s chief executive, Jin-Yong Cai, was on hand for the ribbon cutting and declared the Hashemite Kingdom a “preferred Mideast country” for his institution. (Passing through Egypt on the same trip, Cai said that “domestic and international investors need clarity.”)

The European Investment Bank has been Morocco’s leading outside investor since 2011. Its latest big project, announced in December, was a €420 million loan to the government for transportation and energy infrastructure.

Tunisia has earned praise from the European establishment for its post-Spring progress. “Tunisia is a front-runner both politically and economically,” says Europe-

Aid’s Cornaro. “It is not in the shadow of Egypt at all.”

The EU has given Tunisia €400 million in direct aid since 2011, with €240 million of that committed before the Arab Spring began. Since the revolution the EIB has agreed to lend €500 million; the latest piece is a €270 million commitment for small-business loans extended via Tunisian banks, which was announced in December. The EBRD has done little in the country so far.

In Egypt, meanwhile, the outlook remains muddy. President Morsi’s economic team is a mix of Muslim Brotherhood loyalists and career bureaucrats, analysts say. No clear champion for the reforms that could catalyze Western engagement — no Egyptian Yegor Gaidar or Leszek Balcerowicz, for instance — has emerged.

Under these circumstances, the parliamentary elections evoke more dread than enthusiasm. “The Brotherhood’s popularity has definitely been declining, but the opposition is unorganized and uninspiring,” says Mohammad Abu Basha, an economist at investment bank EFG Hermes in Cairo.

European officials insist they remain committed to a deeper involvement in the countries of the Arab Spring. The EBRD’s Lankes says his bank could boost lending to its target of €2.5 billion a year in the Semed countries once the small matter of opening an office in Egypt is sorted out. “The European Union is sometimes criticized for not being fleet of foot, but we are good at long-term processes,” says the EU’s Mann. “Enlargement to the East took 15 years.”

Whether conditions in Egypt and elsewhere in the region can wait that long remains to be seen.