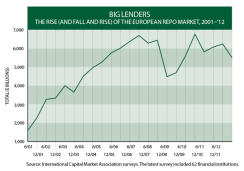

Proposals to reduce risk in the repo market could end up achieving the opposite, experts warn. The repo, or repurchase, market allows financial institutions to borrow cash by pledging securities as collateral. Because it offers secure borrowing, the €6 trillion ($8 trillion) European repo market helped prevent a new credit crunch in the region. “Regulation has pushed the unsecured market to the grave, so the secured market, including repo, is how lenders transact now to protect themselves from counterparty risk,” says Godfried De Vidts, the London-based chairman of the International Capital Market Association’s European Repo Council. Tougher capital requirements for unsecured loans have increased their cost to lenders.

But the Financial Stability Board, which recommends global reforms to Finance ministers and central banks, has put forward tough new repo regulations. The Basel, Switzerland–based FSB published its initial proposals in November, with final recommendations scheduled for September 2013. The most hotly debated proposal is for minimum “haircuts.” A haircut is the extra value of collateral pledged for a cash loan in the repo market. A haircut of 10 percent on collateral with a market value of $100 million, for example, lets the counterparty putting up the collateral borrow $90 million.

In its November report the FSB, which declined to comment, said minimum haircuts could “limit the build-up of excessive leverage.” The board calls for minimum haircuts of up to 16 percent for long-dated securitized products, even larger haircuts for equities outside major indexes and smaller ones for sovereign bonds.

The FSB aims to limit risk for the cash lender. But “what people are forgetting is that the haircut poses a risk on the other side,” says Staffan Ahlner, London-based head of global collateral management at Bank of New York Mellon Corp. Ahlner points out that a compulsory 1 percent haircut on $100 million gives the institution pledging the collateral for cash $1 million in exposure to the cash lender. “If this exposure is to a bank, it might be manageable, but if you’re giving it to a lightly regulated hedge fund, it becomes a mandated unsecured exposure to a counterparty,” he warns. As counterparties respond to this risk, “some institutions will find it harder to borrow cash because of the credit risk, and some institutions will not be able to borrow at all,” Ahlner adds.

He also fears that liquidity could be hit by the minimum haircut rules because the margin created by haircuts reduces the amount that can be borrowed for a given level of collateral. Another worry: A system of different minimum haircuts might encourage cash borrowers to offer bad assets as collateral. For instance, if there’s a 16 percent minimum for all securitized bonds, that could become the standard haircut regardless of asset quality.

Greg Markouizos, London-based global head of Citigroup’s finance desk, says that, regulatory pressure aside, haircuts have become more common since the credit crunch made counterparties wiser to the risks of lending. Given this trend, it may be hard to tell if the FSB proposal has already affected market behavior. Present haircuts can be larger and smaller than the board’s suggested minimums. But instead of obligatory minimums, Markouizos prefers the current “dynamic” system in which cash lenders adjust haircuts to changing conditions. Minimum haircuts will stop cash lenders from doing their own due diligence, he says.

In its report the FSB admitted that large minimum haircuts could reduce repo volumes. But it believes they will combat what it calls the “pro-cyclical” nature of the repo market. The FSB’s reasoning: Cash lenders are liable to demand big increases in haircuts during economic downturns, accentuating the dip in available credit. Backing the board’s assessment are Yale School of Management professors Gary Gorton and Andrew Metrick, who have asserted in influential research that “unprecedented high repo haircuts” on securitized bonds were a main cause of the 2007–’08 credit crisis and that minimum haircuts are a crucial fix.

Observers predict that the FSB will impose minimums. If they’re too high, “the market will, in boom times, find other ways to increase leverage,” says Bruce Tuckman, clinical professor of finance at New York University’s Leonard N. Stern School of Business. One solution is instruments that can mimic repos, like total return swaps. As so often happens, the market may remain one step ahead of regulators.