When Werner Lanthaler took over as CEO of Evotec in March 2009, the Hamburg-based drug discovery company had a remarkable record of consistency: It had never generated a profit in its 16-year history. The company was funneling capital into early-stage research and development, focused primarily on drugs to treat insomnia and depression and to help people quit smoking, but it never hit the jackpot. In 2008, R&D spending hit €42.5 million ($59.5 million) and the company’s net loss ballooned to more than €78 million.

“At that stage the company was in a true crisis,” says Lanthaler. He wasted no time in announcing a radical overhaul of Evotec’s business model. No longer would the company invest only its own cash into the risky endeavor of creating and testing new drug formulas. Instead, it would enter into licensing alliances with other pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies to share the costs of drug development — and the profits that any discoveries produced. In doing so, he slashed Evotec’s R&D spending by 30 percent and trimmed other expenses by 10 percent. “The old product development model just didn’t work,” Lanthaler says. “We had to change something.”

Today, Evotec has partnerships with more than 20 companies, including Germany’s Boehringer Ingelheim, Switzerland’s Novartis and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a Titusville, New Jersey–based arm of Johnson & Johnson. Evotec also has academic partnerships with Harvard and Yale universities. In each case, Evotec receives a base payment for its participation, which can be providing a new drug formulation or the infrastructure for early-stage testing, and then gets additional milestone payments when drugs hit certain specified stages, such as animal testing or preclinical trials on humans. If a drug goes into commercial production, Evotec earns royalties on sales.

The new model is working. Evotec moved into the black for the first time in 2010, posting net income of €3 million as revenues rose 29 percent to €55.3 million. In the first nine months of 2012, the company reported an operating profit of €2.9 million on revenues of €64.2 million.

“Product development for small companies working alone is too expensive and too risky,” Lanthaler says. “Creating an alliance model proved to be the thing that was needed in the industry.”

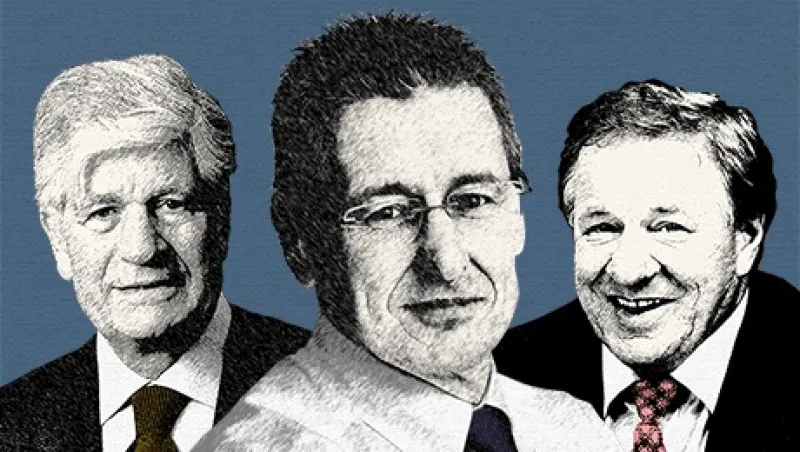

Investors appreciate his transformation of Evotec. Buy-side analysts name Lanthaler as the best CEO in the Biotechnology sector in Institutional Investor’s 2013 All-Europe Executive Team, our exclusive ranking of Europe’s top CEOs, CFOs, investor relations professionals and IR teams.

“Lanthaler had a long and stony way to go to restructure this company,” says a portfolio manager at a Swiss firm that oversees the assets of a European family office. “He promised early to make it profitable, and he always fulfilled his promises. ”

In today’s tough economic climate, which sees much of Europe mired in recession while continued debt troubles in peripheral countries raise doubts about the stability of the euro area, more than ever investors and analysts appreciate companies that can deliver positive results in the face of stiff headwinds.

For some executives, that has meant quick restructuring to adjust to new economic realities. Adidas, for example, abandoned its brand-centered organization in 2009 in favor of two broad divisions: a wholesale channel to oversee sales through third-party retailers and a retail channel to manage direct sales through Adidas’s growing own-store network. The company also closed many regional offices to cut costs.

“The financial crisis was definitely a catalyst for making us reconsider how we should be managing the business going forward,” says chief financial officer Robin Stalker, voted the No. 1 CFO in the Retailing/General sector by sell-side analysts; buy-siders rank him No. 2. The sell side also recognizes CEO Herbert Hainer as the No. 2 chief executive in the sector, and the company’s investor relations team gets a similar ranking from buy- and sell-side voters.

In other cases, innovation has helped companies stay ahead of the curve. For French advertising giant Publicis Groupe, for instance, that meant getting an early head start on the digital transformation of the marketing world. “We were quick to see the change in people’s behavior,” says CEO Maurice Lévy, the favorite CEO in the Media sector among buy-siders and the No. 3 pick among sell-siders. “We saw that mobile communication would be paramount in the future, that the Web would be indispensable in their daily life. This led us to our digital strategy. We knew we had to be embedded in this new world.”

Many companies have sustained growth by focusing on more-buoyant economies overseas. Atlas Copco, the Swedish industrial equipment manufacturer, and Aberdeen Asset Management, the U.K.-based money manager, are impressing shareholders by generating good growth in the U.S. “The profit expectations from investors are immense right now,” says Tim Raiswell, senior director of corporate finance research at CEB, a Washington-based executive research and advisory firm. “European companies have to lock in the cost benefits they’ve realized in the past several years, and they’ve got to somehow grow on top of that. This calls for transformation.”

At Publicis, Lévy began his rethinking in 2005, when the company decided it needed to move toward making digital marketing and services the heart of the business. The first big move came at the end of 2006, when Publicis announced it would buy Digitas, a Boston-based digital marketing firm, for $1.3 billion. That deal set the stage for a spate of others: In August 2009, Publicis said that it would buy Microsoft’s online advertising and marketing firm Razorfish for $530 million. Two years later, it paid $575 million to acquire Rosetta, a Hamilton, New Jersey–based digital marketing group. And in September 2012, Publicis paid $540 million for LBi, a digital agency based in Amsterdam.

Lévy aims to generate half of Publicis’ revenues from digital services by 2018. The company is well on its way. In 2006 Publicis derived about 7 percent of revenues from digital, in line with the wider advertising market. Today digital activities account for more than 35 percent of the ad giant’s revenues, nearly double the 18 percent of the overall advertising market.

“We have been very resilient, including during the crisis from the end of 2008 through 2010,” Lévy says, “and this is thanks to the fact that we already had a strong position in digital.”

Publicis posted a 13.7 percent rise in revenue last year, to €6.6 billion, with digital activities showing 6.6 percent organic growth. Net income jumped 22.8 percent, to €737 million.

Now that the company has built a strong digital platform through acquisitions, it is focusing on organic growth. In early March, Publicis announced that it would partner with Adobe Marketing Cloud to integrate Fluent, a Publicis digital marketing platform product, into Adobe’s digital marketing platform. “Fluent is now part of a suite of Adobe products, and we’ll get a share of those revenues,” Lévy says. “We’re moving to a model that should generate higher returns for us in the future, with higher margins.”

Smurfit Kappa Group, the Dublin-based paper and packaging behemoth, entered the recent economic crisis in a vulnerable position. The company does 75 percent of its business in Europe, which is expected to suffer a further small drop in output this year. It also carried a heavy debt load, a legacy of a €3.7 billion leveraged buyout in 2002 of Jefferson Smurfit, as the outfit was then known.

Smurfit merged with Dutch rival Kappa in 2005, creating Smurfit Kappa, and it returned to the public market with a €1.5 billion IPO in 2007, only to run smack into the global financial crisis. “All of a sudden, while the leverage we had reduced to was very comfortable for us, the equity markets were very uncomfortable, so we had to focus for the last couple of years on paying down debt,” says CEO Gary McGann. “Our strategy has been to drive our net debt down to a level where the equity markets are comfortable in this new world of less risk and more certainty.”

To do that, McGann cracked down on costs. Over the past five years, the company has increased automation and instituted benchmarking metrics in its 350 plants to reduce waste and spread best practices. It has also invested €100 million directly in green and biomass-based energy and co-invested in a €100 million project with other parties. “We took a view that we needed to be as low-cost as possible in the production processes, and as differentiated and as innovative as possible in the offering to the marketplace,” says McGann. Those efforts have slashed annual operating costs by €500 million over the past five years.

At the end of 2010, Smurfit Kappa’s net debt was €3.11 billion, or 3.4 times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization. McGann has since promised investors to keep the company’s debt-to-ebitda ratio below 3, and delivered. At the end of 2012, net debt was €2.79 billion, or 2.7 times ebitda. The company managed to boost net income by 20.9 percent last year, to €249 million, even though revenues dipped marginally, to €7.34 billion. “The company has simultaneously managed to hugely improve its debt maturity profile, lower its debt and dramatically lower financing costs while maintaining a strong focus on operations,” says one Sweden-based equity analyst. The buy side recognizes McGann as the outstanding CEO in his sector, while the sell side ranks him second-best. The buy side also ranks Smurfit Kappa CFO Ian Curley tops among his peers.

Looking forward, McGann says the company will keep its focus on finding ways to mine value in its core European operations rather than trying to shift to faster-growing regions abroad. “Europe is a very important part of our business,” he says. “It is probably one of the most advanced retailing markets in the world. Europe is a part of our business where we just continue to dig deep and find ways to get more efficient, and win the battle in the marketplace in terms of the offering.”

Whereas the crisis prompted Smurfit Kappa to hunker down and hone its existing model, Adidas decided it needed to alter its approach. Traditionally, executives hadn’t thought of the Herzogenaurach, Germany–based company as a retailer. They regarded their few flagship stores as marketing tools and looked to distribution partners for most of the group’s sales. But the crisis led Adidas to search out growth opportunities in emerging markets, where retailing networks were underdeveloped.

“2009 was a great catalyst for further improving the articulation of our longer-term strategy and forcing a change within the group to ensure that we are delivering on that,” says CFO Stalker. The company drew on its model in Russia, where Adidas opened its first store in 1994 because of a dearth of retailing networks there at the time. Today it has 900 stores in Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States and aims to grow the network to some 1,200 stores by 2015. Adidas currently is the market leader in Russia, and its Reebok line is the country’s No. 2 brand. “That has provided us with a lot of learning and also good profitability in this market,” Stalker says.

In 2010 management incorporated those Russia lessons into the global business and set up two channels, each with its own management team: one for the traditional wholesale business of supplying other retailers, and a second for sales through company-owned stores, which currently number 2,446. The company also adopted what it calls its Route 2015 strategy, which calls for boosting sales by nearly 50 percent to €17 billion in 2015, growing earnings at a compounded annual rate of 15 percent and achieving an operating profit margin of 11 percent.

“When we first announced this Route 2015, there was a certain amount of skepticism in the market,” Stalker admits. “It was called too ambitious — especially our profitability goals.” Today, however, Adidas is on track to hit most of its targets. Revenues rose 12 percent last year, to €14.9 billion, with wholesale revenues rising just 2 percent and retail sales jumping 14 percent. The company now gets nearly a quarter of its sales from its own stores. Last year Adidas had an operating profit margin, before exceptional charges, of 8 percent.

Stalker emphasizes that a key task for him and the company’s investor relations department is to communicate the group’s progress to investors and to point out where challenges still exist. “We need to make clear to shareholders how we’re going to achieve these profitability goals in the future,” he says. “I think we’ve been honest and open about things that aren’t going as well as we would like.”

A prime example is the weak performance of the Reebok brand, which Adidas bought in 2005 for $3.8 billion. The company took a goodwill write-down of €265 million last year, mainly on Reebok, which caused net income to fall 14.2 percent, to €526 million.

John Paul O’Meara, vice president of investor relations at Adidas, says he tells investors that Reebok’s problem is a lack of consistency in how the brand has been positioned. The company is working to establish Reebok as a fitness brand, which it promotes through a collaboration with the CrossFit conditioning program.

O’Meara — ranked the top IR professional in Retailing/General by buy-siders and No. 2 by sell-siders — credits his tenure as a former sell-side analyst at Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein with giving him insight into what investors really want to hear. “What comes from years of being in the industry is an understanding that most people are interested in the negative stuff and not the positive stuff,” he says. “The positive stuff is a given; it’s how you deal with the challenging things that’s most important.”

With the European economy still flatlining, one of the biggest questions facing companies is where to find growth. Emerging markets continue to figure in the strategies of many corporations, but for a good number of companies in this year’s All-Europe Executive Team, the U.S. is the place to be.

“In many ways, the U.S. is a known quantity for European executives. They know the banks, they know the customer base there, they know the politics,” says CEB’s Raiswell. “And all of these things are relatively stable compared with emerging markets, or even the European market right now. If I’m a corporate executive, I want to bet on the sure thing — even if it doesn’t necessarily represent barnstorming growth.”

Last year Atlas Copco announced that the U.S. — where its customers include Boeing, Caterpillar, Ford Motor Co., General Motors Co. and John Deere — had overtaken China as its biggest market, generating 11.23 billion kronor ($1.7 billion) in sales, or 12.4 percent of group sales. In a bid to cement that position, the Swedish tool and equipment maker made two recent acquisitions: Salt Lake City–based drill bit manufacturer NewTech Drilling Products in October 2012 and Houston Service Industries, a Texas-based producer of low-pressure blowers and vacuum pumps, in January 2012, for undisclosed sums. The company also added several hundred American employees to its head count, primarily in sales and service.

CEO Ronnie Leten says the company used to operate on the assumption that “what works in Europe should work in the U.S.” More recently, however, Atlas Copco has realized it can generate better returns if it tailors products for the American market to give customers the “different flavor” they seek. U.S. customers prefer products with a more robust look than their European counterparts, he says, and they are more concerned about the life-cycle cost of a product than Chinese customers, who tend to focus more on low initial cost. Adapting to these different preferences has forced the company to temper its obsession with efficiency, Leten acknowledges, but, he adds, “lower costs isn’t the big thing. Return is what matters.”

Leten’s approach is a hit with the market. He is named as the top CEO in his sector by both buy- and sell-side voters. The company’s CFO, Hans Ola Meyer, also emerges as the favorite among both sets of analysts, and its investor relations operation is voted one of the top three in the sector by the buy and sell sides. “The team at Atlas Copco acts on the long term, and not in the typical Wall Street fashion,” says Arne Karlsson, an analyst at Alecta Investment Management in Stockholm.

Technip, a Paris-based oil field services firm, has been expanding its presence in the U.S. too, taking advantage of the revival of oil and gas production in the country.

Five years ago, half of the French concern’s order backlog came from onshore oil and gas projects in the Middle East. Today the Americas provide 30 percent of its backlog and the Middle East only 11 percent.

“We now have a much more balanced portfolio of projects,” says CEO Thierry Pilenko, who is voted the best chief executive in Oil Services by both the buy and sell sides. “In particular, our presence in the Americas has grown very significantly.”

Pilenko explains that the decision to diversify the company’s business was made before the global financial crisis, but when that storm hit in 2008 and ’09, the steps the company had taken to vary its business helped it emerge from the tempest unscathed. During and after the crisis, energy sector competition increased in the Middle East. By contrast, the boom in North American oil and gas production boosted Technip’s business and encouraged the company to bulk up further in that market.

Last August, Technip paid $225 million for the process technologies and engineering capabilities of Houston- based Stone & Webster, which services the refining and petrochemical industries. Pilenko says the deal will enable Technip to benefit from an expansion of the petrochemical business, which he believes “is about to explode in North America” because of an abundance of low-cost natural gas, which both drives down the cost of energy and serves as a raw material for making plastics and other materials.

Technip’s other recent U.S. acquisition was the $937 million purchase of Houston-based Global Industries in September 2011. The deal enlarged Technip’s fleet of subsea pipelay and construction vessels and bolstered its presence in the Gulf of Mexico.

Aberdeen Asset Management also sees the U.S. as the market offering the greatest growth potential. The bulk of the Scottish money manager’s business currently comes from Europe and the Middle East, but the firm believes its growing specialty of offering emerging-markets investments gives it a strong card to play across the Atlantic.

“America still has the vast bulk of the world’s wealth,” says Martin Gilbert, who ranks as the top CEO in his sector among both the buy side and the sell side. CFO William Rattray places as the favorite financial officer of the sell side in his sector and the second-favorite of the buy side. “As people in the U.S. are looking more globally to invest in emerging markets, we think that’s an opportunity for us,” says Gilbert.

Aberdeen has been ramping up its exposure to emerging markets in recent years, particularly in fixed income. The firm currently has £80 billion ($122 billion) of its £187 billion in assets under management invested in EM debt. But Gilbert is careful not to promise more than he can deliver. In February 2013, Aberdeen imposed a “soft close” on some of its emerging-markets funds by levying a 2 percent initial charge in an effort to stem inflows. “The key thing, when you feel you’ve got capacity issues, is to not take more money and to really look after your existing clients,” Gilbert says.

Banco Santander’s strategy of targeting growth in key overseas markets has helped that bank weather the financial crisis in Spain, its home market. “An important advantage for us in the crisis was our diversification,” says José Antonio Álvarez, who is voted the favorite CFO in his sector by the sell side and one of the top three picks of the buy side. Banco Santander’s CEO, Alfredo Sáenz Abad, is dubbed the best in his sector by the sell side. Santander seeks diversification and scale, Álvarez says. It aims to have a market share of 10 percent or more in the countries or regions where it operates. In addition to its home market, Santander has a major presence in the U.K., a big network across Latin America and a foothold in the U.S., where it owns Boston-based Sovereign Bank.

“We’ve been marching in two different wars,” says Álvarez. One of those wars is in the mature markets of Europe and the U.S., where growth has been scarce, while the other is in emerging markets, he explains: “Fifty percent of our profits come from emerging markets, where we’ve been growing quite nicely.” In 2012 half of the group’s profits came from Latin America, including 26 percent from Brazil alone. By contrast, Spain contributed just 15 percent.

Investors appreciate the bank’s strategy. “They were wise enough in good times to regionally diversify their investments, so that when the crisis struck in Spain they had a strong and reliable stream of cash flows coming from other parts of the business,” says a London-based money manager.

At home, Santander has been aggressive in trying to reduce its exposure to the country’s hard-hit real estate market. The bank sold 33,500 properties in Spain last year and set aside €6 billion in provisions for Spanish real estate loans. The bank reduced its Spanish property lending exposure to €13.5 billion at the end of 2012, down nearly 70 percent from €42 billion four years earlier.

Santander has also been honing its efficiency in response to the financial difficulties in Spain and the rest of Europe. The bank’s cost-to-income ratio stood at 46.1 percent last year, compared with 62.8 percent at HSBC Holdings, 64 percent at Barclays and 90.8 percent at Deutsche Bank. It’s too early to say when the operating environment in Spain, and Europe, will improve, but Álvarez and other members of the All-Europe Executive Team aren’t waiting for the economy to rescue them. They are finding ways to thrive even in the toughest of conditions.

“I think when the dust settles on what’s happened in the last few years in Europe, what you’ll see is that the winners have become very adept at learning from their investment process,” says CEB’s Raiswell. “Basically, they’re the ones who are very disciplined about feeding that intelligence back into the investment process.” • •