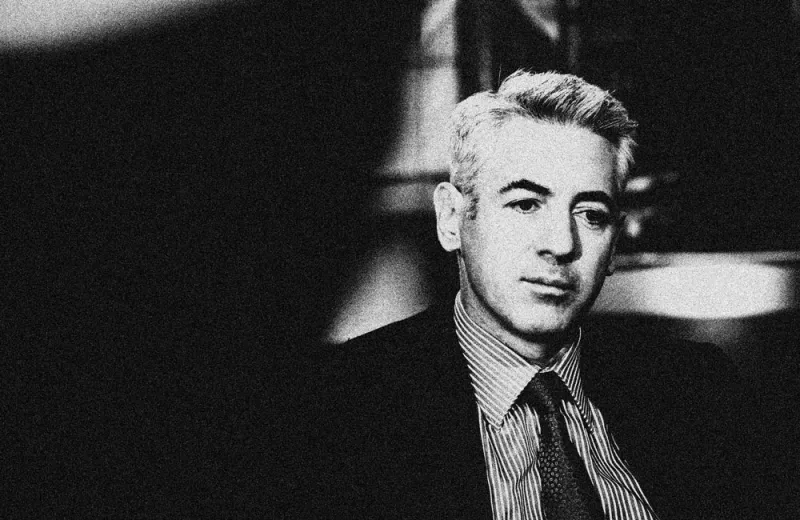

When Bill Ackman launched a $4 billion special purpose acquisition company two years ago, it looked like a brilliant move. The Pershing Square Capital CEO had just made $2.6 billion in a timely Covid short bet, recapturing the magic that had made him a star. Meanwhile, the markets were in turmoil, and so-called unicorns — private companies worth $1 billion or more — were looking for a way to go public.

Ackman thought his SPAC would meet the moment perfectly. In a letter to investors this week announcing the liquidation of his SPAC, he wrote, “We launched PSTH [Pershing Square Tontine Holdings] in the depths of the pandemic because we believed that the capital markets would likely be impaired from the economic uncertainty created by the pandemic.” But Ackman admitted he was wrong: “The rapid recovery of the capital markets and our economy were good for America but unfortunate for PSTH, as it made the conventional IPO market a strong competitor and a preferred alternative for high-quality businesses seeking to go public.”

Ackman’s decision this week to return capital to investors was so expected that it seems almost anticlimactic after all the news swirling around his SPAC over the past two years — not to mention the troubles of the entire market. Close to 600 SPACS are still looking for companies to merge with, and half or more are widely expected to follow Tontine’s path of demise. At least seven other SPACS launched since 2020 have already been liquidated, according to SPAC Insider. And even some of those who’ve found a partner are in trouble: Thirty deals have been canceled this year, according to Bloomberg.

But if anyone could have beaten the odds, one might have expected it to be the Pershing Square CEO. He was no novice to the world of SPACs, having bought Burger King through one in 2012. And this time around, Ackman devised an unusual structure that he felt would avoid some of what are now widely recognized as the pitfalls of SPACs. For example, Pershing Square took no free sponsor shares and worked out a warrant structure that would keep the investors in his IPO from bolting, as they often do once the blank-check SPAC merges with a real company. It also didn’t need to secure a PIPE — or private investment in public equity — to help consummate the deal; Ackman would supply the cash.

But the hedge fund manger couldn’t overcome the Covid-induced mania that swept the markets, making the valuations of many private companies — like Airbnb or Stripe — too rich for him. Meanwhile, the Securities and Exchange Commission began cracking down on SPACS — including refusing to approve a novel deal struck by Ackman.

That deal was not a merger to take a company public, which is the way SPACs typically operate. Because Tontine was so large, and many other potential targets were going the IPO route, the SPAC planned to make an investment in Universal Music Group when it was spun out of Vivendi. After regulatory hurdles nixed the deal, shares of Tontine tanked, causing millions of dollars in losses for the many retail investors that saw Ackman’s SPAC as the best of the lot. Then lawyers hoping to make a test case of Ackman’s SPAC sued it, claiming it was really an investment company and should be subject to stricter rules.

Ackman tried to find another deal, but as he explained to investors, the once-ebullient SPAC market had turned ugly. He cited the poor performance of SPACS that have completed deals during the past two years (an index ETF of the post-merger companies is down 75 percent this year alone), along with high redemption rates and a pullback of PIPE financing, which increase the dilution from outstanding shareholder warrants.

And while the bubble previously created difficulties, the immediate and swift return to bear market territory is likewise problematic. “High quality and profitable durable growth companies can generally postpone their timing to go public until market conditions are more favorable, which limited the universe of high-quality possible deals for PSTH, particularly during the last 12 months,” Ackman told investors. He noted that “while there were transactions that were potentially actionable for PSTH during the past year, none of them met our investment criteria.”

Last on the list of negatives was the litigation pending against Ackman’s SPAC, which claimed that PSTH should fall under that Investment Company Act’s provisions because it invests IPO proceeds in government securities held in trust while searching for a partner. That litigation presaged the SEC’s tough new rules proposed this year, and Ackman said the “risk and uncertainty” about the pending litigation, combined with the new rules, was hampering its ability to do a deal.

Lawyers suing Tontine have previously said in court filings that they will withdraw the litigation if the SPAC liquidates and returns capital to investors. Meanwhile, its objective — which was to get the SEC to take notice — seems to have been successful. One of the proposed SEC rules will consider SPACs subject to investment company rules if they haven’t announced a deal within 18 months and completed it within two years.

With all these things going against it, this week Ackman told investors in Pershing Square Tontine Holdings that the SPAC would return their money. As is the design in SPACS, if a deal isn’t struck within a certain time period — typically 24 months — it has to return the money it holds in trust. In Tontine’s case, that comes to $20 per share, a price close to which the stock has traded for the past year. Warrants expire worthless — including the one that Pershing Square owns.

But, as is typical for Ackman, he’s not giving up.

“With the SPAC and IPO market effectively shut today, now is a highly opportunistic investment environment for a public acquisition vehicle which does not suffer from the negative reputation of SPACs,” he said. Although the SEC has put roadblocks in the way, Ackman is still trying to launch Pershing Square SPARC Holdings, Ltd., which would issue publicly traded, long-term warrants called SPARs. In the case of the SPARC, investors would not have to put money upfront, eliminating that legal minefield.

Pershing Square SPARC filed a revised registration statement with the SEC on June 16. If it ever gets off the ground, common share and warrant investors in Ackman’s SPAC will receive warrants on the new vehicle.