The Closest Thing to White Supremacy I’ll Ever Get to Write About

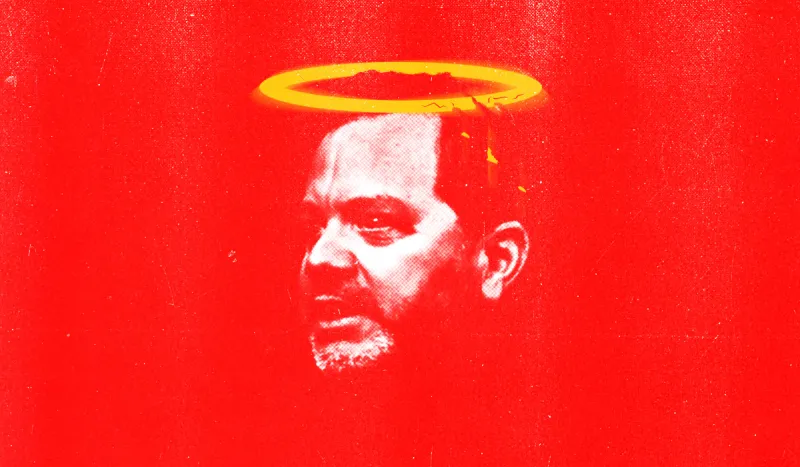

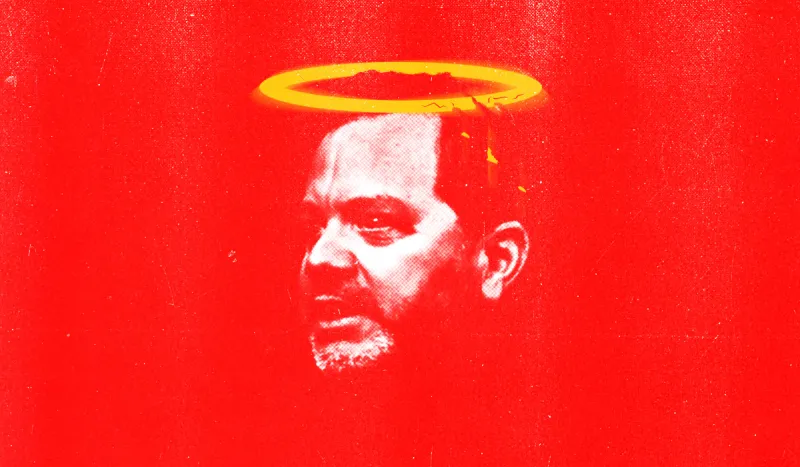

It’s not Charlottesville, but the hypocrisy of TPG’s William McGlashan — the prominent impact investor caught up in the college acceptance cheating scheme — is as despicable as I’ve ever seen.