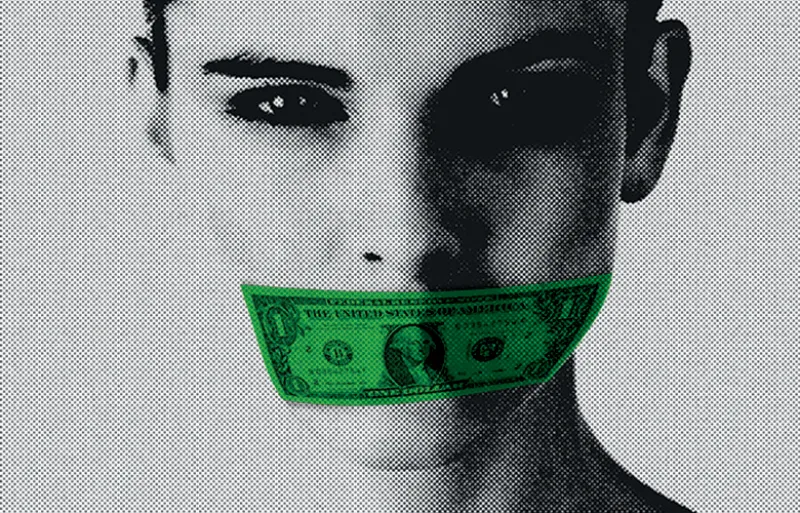

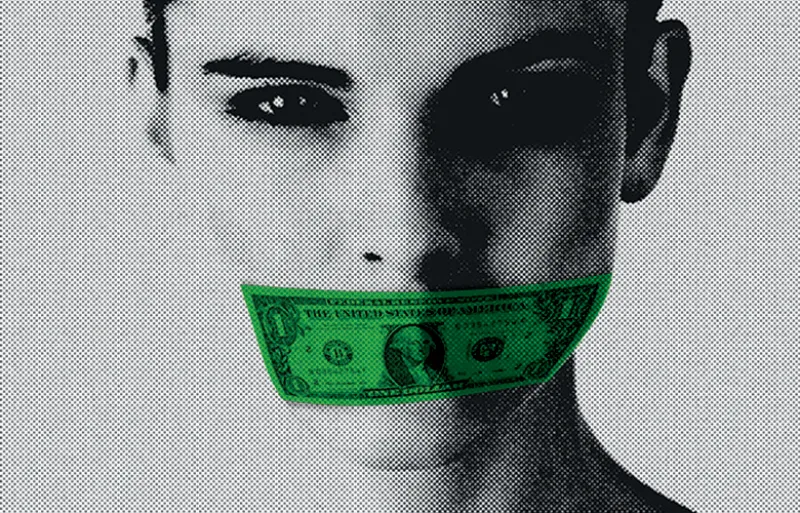

This Column Is Meant to Make You Uncomfortable.

Questions must be asked about the deafening silence surrounding sexual harassment in asset management — an industry that, to outsiders, would seem absolutely ripe for Harvey Weinstein– and Matt Lauer–style abuses of power and privilege, columnist Angelo Calvello writes.