Where do you produce your entrepreneurs from?" asks Lee Kuan Yew. "Out of a top hat?" The 78-year-old founder, ex-prime minister and now senior minister of Singapore complains during an interview with Institutional Investor that "there is a dearth of entrepreneurial talent" among Singapore's 4 million people. The root of the problem, he explains, is "an East Asian reverence for scholarship": The Chinese typically value education above all, so the ultimate aim is to become a mandarin , a shi, or scholar. Second in esteem is the nong, or farmer; third is the gong, or worker; and fourth and last is the shang, or merchant , the entrepreneur.

What Singapore must do, therefore, says its elder statesman, is overcome this antientrepreneurial ethos by promoting "little Bohemias": informal enclaves where the sometimes stifling sense of order that pervades this sophisticated city-state will give way to creative chaos (measured out carefully, to be sure) so as to generate innovation, stimulate entrepreneurship and ultimately spawn the kind of ferment epitomized by early Silicon Valley.

It's an astonishing notion: Lee, the micromanager of one of the most successful (and controversial) socioeconomic experiments of the latter half of the 20th century , Singapore achieved dazzling 8.9 percent average annual growth from 1965 through 2000 , is now proposing, along with Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, that this straitlaced, all-encompassing command-and-control economy nurture, well, free spirits. This is a country that was built, after all, on discipline and conformity, in which the government owns six of the ten largest companies on the Singapore Stock Exchange and bans everything from Cosmopolitan magazine to chewing gum.

"We have to start experimenting," Lee insists. "The easy things , just getting a blank mind to take in knowledge and become trainable , we have done. Now comes the difficult part. To get literate and numerate minds to be more innovative, to be more productive, that's not easy. It requires a mind-set change, a different set of values." The idea , no, plan , is for Singapore to hothouse budding entrepreneurs capable of starting companies that can go on to expand regionally and globally. Headquartered in and committed to Singapore, these indigenous enterprises would show no inclination to decamp to China or other ostensibly greener pastures. And by producing brand-name and knowledge- and technology-intensive products and services that countries with cheaper labor cannot readily copycat, these Singapore Inc. start-ups would allow the city-state to maintain its competitive edge for years to come. Or so its leaders believe.

All the same, Singapore's old "values" are not quite ready to be chucked out like one of the old videocassette recorders the city-state used to manufacture. The country grew prosperous by attracting big business, not by nurturing start-ups, and Singapore's current business model has plenty of muscle and momentum left, especially for high-end manufacturing of disc drives and other computer paraphernalia (though no longer DVDs, much less VCRs). Some 6,000 multinationals, including such technology stalwarts as Hewlett-Packard Co., Philips Electronics and Seagate Technology, account for 42 percent of the city-state's GDP. "What has worked, better keep at it," says Lee.

Yet the senior minister and Prime Minister Goh recognize that Southeast Asia , Singapore's customary commercial zone , has lost much of its drive and, more important, that China poses an enormous long-term challenge as contractor to the world. Politicians from Tokyo to Delhi are reeling from China's rapid emergence as a manufacturing powerhouse.

Even as Southeast Asia has struggled to recover from 1997's financial crisis and last year's global downturn, China has surged ahead. It recorded GDP growth of 7.9 percent last year and 8.1 percent in 2000. This year it's expected to grow a further 7 percent.

"It's scary," declared the Singaporean prime minister in a National Day speech last August. "China's economy is potentially ten times the size of Japan's. Just ask yourself: How does Singapore compete against ten postwar Japans all industrializing and exporting to the world at the same time?"

What's more, warns Rajeev Malik, a senior economist at J.P. Morgan Chase Bank in Singapore, "China is catching up faster than Singapore is leaping ahead." And as Christopher Gee, head of research at ING Baring Securities (Singapore) notes, it takes a "long while to shift an economy, so the government must start to act and to act decisively."

Can Singapore pull off this commercial and cultural metamorphosis?

That is an intriguing issue. Singapore has had to be flexible before, shifting from textiles to rudimentary electronics and then to sophisticated electronics, chiefly computer gear. But the transformation to an entrepreneurial mind-set is of another magnitude culturally, and some think that the city-state's rigid society may have irreparably blunted its people's entrepreneurial spirit. "Risk-taking is not part of the culture here," contends PK Basu, Credit Suisse First Boston's chief economist for Southeast Asia. "Creativity does not flow naturally."

"Singapore's authoritarian system of governance is incompatible with an innovation-led economy," adds one foreign critic. Senior Minister Lee guffaws at this, calling it "that argument that I've heard over the past four decades." If you make the case that a "free-for-all society" is needed to produce great innovation, he asks, "how come so few countries in the developing world have succeeded?"

In seeming to tamper with its successful formula, Singapore is in reality confronting the distinct possibility that its long-standing business model is well on its way to becoming obsolete. Last year the city-state suffered its worst recession since independence in 1965: The economy contracted 2 percent, the sharpest decline of any major Asian country. Unemployment hit a 15-year high of 4.7 percent. The global downturn, compounded by the September 11 terrorist attacks, rattled the country's dominant electronics sector: Sales of integrated circuits , the city-state's principal export , fell nearly 33 percent, and disc drive shipments were off almost 26 percent.

Rest assured, however, that Singapore's prosperity is not in any immediate danger. Even amid last year's gloom and doom, Singapore was able to attract 9.2 billion Singapore dollars ($5.1 billion) of foreign investment, about the same amount as in 2000. Minister of Trade and Industry George Yeo asserts with a certain understatement that "even if we do nothing for the next five to eight years, we still can get by." Most economists see Singapore bouncing back as soon as this year, along with the U.S., its biggest customer. CSFB's Basu predicts a "huge growth surprise" and points out that the economy grew 9.9 percent as recently as 2000. Goldman, Sachs & Co. doesn't anticipate that kind of spike but still expects solid 3.5 percent growth in 2002.

As it is, Singapore, whose per capita GDP has grown more than 30-fold over less than four decades, now has a higher per capita income ($24,740) than France or the U.K., reckons the World Bank. And a recent World Economic Forum survey of global competitiveness that considered everything from creativity to the availability of financing to the business climate ranked Singapore fourth, down from second in 2001, but behind only Finland, the U.S. and Canada.

On the distant horizon, however, are clouds as thick as the smoke pouring from the factories in Guangdong. Back in the early 1990s when the Southeast Asian tiger economies were in overdrive, they absorbed 60 percent of all the foreign investment in Asia; China had to content itself with less than 20 percent, and the rest was divvied up among Japan, India and Northeast Asia. But in 2000 Southeast Asia attracted just 10 percent of total investment in Asia; China, meanwhile, sucked up 30 percent, or some $41 billion worth. The remainder went mainly to Northeast Asia.

China, says Lee, is "a vacuum cleaner for foreign direct investment." And although Singapore does not yet compete head-on with China in electronics , the city-state manufactures those higher-value-added computer devices, while China turns out mainly TVs and radios , that time will surely come if investment trends persist and Singapore doesn't succeed in shifting its strategy.

Indeed, in mid-April Dutch electronics giant Philips Electronics, one of the largest multinational investors in Singapore, indicated that it would shift its Asian regional headquarters to Hong Kong to save costs and be nearer China, its biggest Asian market. Ironically, a government committee tasked with advising Singapore on how best to retain manufacturing companies is headed by Philips Electronics Singapore CEO Johan van Splunter.

Another threat to Singapore's vitality can be found in its own backyard. As the provider of financial, logistical and other business services for neighboring Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, Singapore feels the pain when their economies suffer, and none has fully recovered from the 1997 financial crisis (see Special Asia Report). Politics have thwarted vital corporate and bank reforms.

"Singapore is sitting in a part of the world that is in serious danger of becoming an economic backwater," says Bruce Gale, Southeast Asia analyst for political and security risk consultant Control Risks Group in Singapore. "The trend of investment moving away from Southeast Asia to China was apparent even before September 11. It will accelerate as a result of September 11, because investors are going to say, 'Where are the large Muslim populations in Asia? Southeast Asia, so let's stay away.'"

To address these mounting concerns, Prime Minister Goh set up an Economic Review Committee in December to draw up a blueprint for building the new Singa-pore. To complement the work of the ERC, he also formed a Remaking Singapore Committee to determine what kind of political and social changes the city-state should adopt. Headed by Lee Kuan Yew's son Lee Hsien Loong, who is minister of Finance and co,deputy prime minister, the Economic Review Committee comprises more than 60 prominent private sector members, such as Singapore Airlines chairman Koh Boon Hwee and Deutsche Bank Asian-Pacific CEO Robert Stein, as well as top government officials, including co,deputy Prime Minister Tony Tan and Minister of Trade and Industry Yeo.

The ERC's brief is broad. Is Singapore too dependent on multinationals and electronics products, which account for 61 percent of the city-state's nonoil exports? What can Singapore do to meet the Chinese threat? Should manufacturing still account for one quarter of GDP in the Information Age? Can the lack of local entrepreneurship be traced to a paternal and overbearing government that remains too involved in the economy?

The ERC's seven subcommittees are examining specific issues ranging from how to promote entrepreneurship and new service industries to how to win and retain manufacturing investment. "We are having to work harder and harder to bring multinationals in," confides co,deputy Prime Minister Lee. "At what point do you decide this one is worth my while bringing in but that one I will have to incentivize so heavily that I will allow it to go some other place?"

Coming under the committee's scrutiny will be critical components of Singapore Inc.'s existing economic structure, such as the role of the mandatory pension scheme (see story below) and of state-owned enterprises (see story below). Also on the agenda: taxes, wages and land costs. Although the ERC isn't expected to deliver its report until August or September, some preliminary recommendations designed to spur competitiveness in the short term were unveiled in mid-April. Key among these: a proposal that top corporate and personal tax rates be slashed from 24.5 percent and 26 percent to 20 percent over three years. "The status quo is not tenable," declared Senior Minister of State for Trade and Education Tharman Shanmugaratnam, chairman of an ERC subcommittee on taxation, wages and land. "Companies are moving, jobs are being lost, and more importantly, even when the economy recovers, the jobs aren't necessarily going to come back."

The thrust of the ERC's ultimate conclusions is already clear: Along with promoting entrepreneurism, it will urge greater diversification into "exportable service" industries, such as health care, education and biomedical sciences, as well as further development of financial services.

Singapore targeted its financial sector for stardom in 1997, easing up on draconian banking regulations and allowing foreign institutions more scope to compete with indigenous banks and fund managers. In combination with business services, the financial sector currently accounts for 17 percent of GDP. Now the ERC's services subcommittee is contemplating what Deutsche Bank's Stein calls a "paradigm shift": identifying just one or two financial services specialties that Singapore can pursue "to put it in a position of regional and global dominance," as he puts it.

Stein, who heads a working group within the services subcommittee, cites Switzerland in private banking, Dublin in back-end processing and Delaware in company registration as examples of places with dominant financial services activities. "There is no globally relevant financial ser-vice in Singapore currently to put it in a strong regional and/or global position," points out Stein. "The approach of the committee is to examine in which niche or niches Singapore has a sustainable comparative advantage." Singapore has traditionally focused on the front-end, capital markets aspects of financial services. But the subcommittee is studying opportunities in back-end processing to capitalize on the city-state's technology platform and accounting and legal skills.

The committee also envisions expanding Singapore's role as an upmarket health clinic for the region. Raffles Medical Group, a provider of hospital and outpatient medical services, estimates that of the 85,000 patients admitted to Singapore's 13 private hospitals in 2000, 40 percent were from outside the city-state. In all, Singapore has 26 hospitals, with 11,798 beds, for a population of just 4.3 million. "The potential is great , half the population of the world is within seven hours of Singapore and these people are becoming more affluent by the day. And they want to have better health care," says Economic Development Board chairman Teo Ming Kian.

The connection between providing hospital care and manufacturing drugs and medical devices is an obvious one, and Singapore is already making a brand name for itself in biomedical sciences. Such pharmaceutical giants as France's Aventis, and American companies Merck & Co., Pfizer and Schering-Plough Corp. have established pill plants in the city-state. The U.S.'s Eli Lilly and Co. has made Singapore its regional hub for clinical trials, and Germany's Siemens has begun researching new medical products there. The biomed segment received S$900 million in mostly foreign investments last year, up slightly from 2000's S$845 million, and accounted for 5 percent of Singapore's manufacturing output, or S$6.6 billion. The development board aims to double the biomed contribution by 2010.

Singapore's ambitions in education are even more audacious. It wants to be nothing less than Southeast Asia's Ivy League, Oxbridge and Tokyo University combined. By becoming a world-class teaching center with a reputation for cutting-edge research, the city-state figures it can draw the most talented professors as well as (tuition-paying) students. Moreover, Singapore-based companies , particularly the knowledge-driven enterprises it is seeking to cultivate , should benefit from the insights of local think tanks, not to mention a deeper talent pool of graduates.

The city-state has made an impressive start on this academic-industrial complex. The University of Chicago Graduate School of Business and Paris-based Insead have set up minicampuses in Singapore. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, the Georgia Institute of Technology and Johns Hopkins University are all offering courses locally in conjunction with Singaporean universities.

This is the easy part. The great challenge for Singapore's paternalistic leaders is how to breed entrepreneurs. The notion of a government planning entrepreneurship is, of course, a tad weird, as co,deputy Prime Minister Lee acknowledges. "If you believe in the free market," he says, "then you'd say this is none of our business."

But this isn't the first time that the government has sought to put more venture in its capitalists. Initiatives to encourage entrepreneurial activity date back almost a decade and include such things as tax incentives, amendments to the harsh bankruptcy law, awards and government-sponsored venture funds. Yet according to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor , a joint project of the London Business School, Babson College in Massachusetts and the Kauffman Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership in Kansas , Singapore stubbornly remains one of the least entrepreneurial societies in the developed world.

The project's 2001 study of entrepreneurial activity in the world's top 29 economies measured how many people out of 100 were trying to start a business or were running one that was less than 42 months old. Singapore placed 27th, fractionally ahead of Japan and Belgium. Mexico came first, with 18.7 entrepreneurs per 100, while the U.S. ranked 11th, with 11.7. The number for Singapore: a mere 5.2.

The study concluded that, in Singapore's case, the biggest barrier to entrepreneurship was not antipathetic laws or lack of capital but an unsupportive culture. The researchers found that Singaporeans have a preference for working with large, established organizations, along with a fear of failure and not enough familiarity with or respect for the entrepreneurial community. They singled out a paucity of existing entrepreneurs to serve as role models and an educational system that fails to foster creativity and personal initiative.

The government acknowledges that Singapore suffers from an entrepreneur gap. Minister of State Raymond Lim, who oversees the ERC's subcommittee on entrepreneurship, contrasts Singaporeans with Taiwanese: "People say that if you are a chap working for a multinational company in Singapore and you leave to start up your own company, your friends will ask you, 'What went wrong? Why are you doing this?' In Taiwan if you start a career in an MNC and after a certain time you are still there, your friends ask you, 'What's wrong? Why are you still there?'"

Perhaps Singaporeans have become too comfortable under a paternalistic government that panders to their needs, suggest others. Asked why Singaporeans aren't more entrepreneurial, Singapore Airlines chairman Koh responds, "In Singapore the problem is people aren't hungry." China, like Singapore, has a Confucian culture, Koh notes, but entrepreneurs thrive there. "The people are hungry," he says.

Minister of Trade and Industry Yeo goes so far as to voice doubts about whether the government should even be in the business of trying to hatch entrepreneurs. Singapore, he suggests, should follow the example of Venice, Milan and Florence. "How did they bring in talent?" he asks. "By opening the doors, not by scouring for the odd Venetian, Florentine or Milanese entrepreneur. If you really want those few odd individuals who make a big difference wherever they are, I think it is better if you reduce taxes, you reduce the hassle factor, you make it easier for people to make money and do the things they want to do, and they will come."

Singapore has always welcomed talented foreigners , working papers are easy to obtain if you're educated or accomplished , and Yeo sees this tradition as intrinsic to Singapore's strategy. Indeed, he regards it as a key competitive advantage, noting that "not many countries can open their doors the way we open our doors." Singapore plays host to some 750,000 foreign workers.

All the same, Minister of State Lim, a former managing director of DBS Securities, hasn't given up on homegrown entrepreneurs. He argues that relaxing business regulations would help promote entrepreneurship, and his subcommittee is studying a "sunset clause": All regulations on the books would have to be reviewed after a certain period before being renewed. "It's not for the person who is being regulated to explain why he should not be regulated," Lim says. "It's for the person who wants to regulate you to make the case why it is necessary to regulate your business. This is the mind-set change we need."

Lim also proposes that entrepreneurs ought be able to become "fabulously rich" and be held up as role models for society. The ERC is almost sure to advocate tax incentives of some kind. Senior Minister of State for Trade and Education Shanmugaratnam, meanwhile, has urged that the committee look into a government fund to finance and coinvest in promising start-ups.

But lower taxes and ready capital don't deal with the biggest impediment to letting a thousand entrepreneurs bloom: Singapore's controlling, top-down political culture. As Lim concedes, it can be a deterrent to "greater creativity, greater willingness to do things in a different way, a greater willingness to challenge the orthodoxy."

The minister of State himself exhibits the independent-minded streak of an entrepreneur, and that has gotten him into trouble in the past. The founder of Roundtable, a discussion group that has dared to take up civic policy issues, he has been described by newspapers as a "renegade" and a "radical." In April last year he and several other Roundtable members were peremptorily summoned to a police station to explain why they hadn't applied for a seminar permit, a plain instance of harassment.

So when the Lees' ruling party invited this uppity outsider to run in last November's elections, it shocked political observers, but also cheered them as further evidence that Singapore's politics continue to evolve. The debate in government-controlled papers has become more robust, and co,deputy Prime Minister Lee said in February that there will be "a progressive opening of political space."

This isn't to suggest that the government brooks serious opposition. But it has shown, from time to time, that it is capable of change. "If this government had closed minds, we wouldn't have got anywhere," says Senior Minister Lee. He launches into a discourse on how entrepreneurial creativity enabled the U.S. to make a comeback from the dark days of the 1980s, when it was being "overtaken by the Japanese and the Germans, who produced better products than Americans did, whether cars, televisions sets, computers, whatever." That was "quite a feat," says Lee, and the lesson has not been lost on the senior minister: "We have to somehow incorporate part of that [creativity] into our culture, into our mind-set and our values." In a recent speech he listed 23 successful local start-ups (see story above) and boasted that for a small economy like Singapore's, it was "not a bad start." But only a start.

Keeping the Inc. in Singapore Inc.

How to create more entrepreneurs dominates the debate over Singapore's new economic strategy (top story). But investors are also awaiting the government's not unrelated conclusions on whether to dispose of the companies it already owns.

Six of Singapore's top ten listed companies by market capitalization , Singapore Telecommunications, DBS Group Holdings, Singapore Airlines, Singapore Press Holdings, ST Engineering and Chartered Semiconductor , are wholly or largely owned by the government. Altogether, government enterprises account for 12.9 percent of Singapore's GDP.

Economists contend that the government would create more growing room for private-sector initiatives if it were to substantially divest its company holdings. "Singapore has grown big because of a high degree of public-sector control," says Christopher Gee, head of research at ING Baring Securities (Singapore). "This has crowded out the private sector and stifled entrepreneurship."

To blunt such criticisms, the blue-ribbon Economic Review Committee appointed by Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong to study Singapore's options is likely to recommend a tougher law to promote competition. Minister of State Raymond Lim, whose ERC subcommittee is investigating this notion, says such a law could help ensure a level playing field and provide the regulatory muscle to tackle abuses of market power. "This is one of those things that, if done properly, could have a big positive impact on the private sector," says Rajeev Malik, a senior economist with J.P. Morgan Chase Bank in Singapore.

But bolder measures seem unlikely for now. Minister of Trade and Industry George Yeo acknowledges that the prospect of divesting the government's prime assets is a thorny issue. "Should we now divest quickly?" he asks. "There's no agreement even among the ministers as to how this should be done. My own instincts are that they are all precious assets, and as many of them as possible should be developed into multinationals, and in the process the government's stake in them should be reduced."

Yeo doesn't want the companies to lose their Singaporean character, however: "If they were divested and became part of American or Japanese or European MNCs, for which this is just another acquisition, and Singapore is not a key element in their global plan, we would have lost out as Singaporeans."

The government does appear to be inclined to pay more heed to the concerns of government enterprises' minority private shareholders. Investors have criticized the companies for paying excessive prices for overseas assets in a bid to carry out Singapore's long-term strategy of building an "external wing" to the economy to become more competitive. Investors have had reason to be upset. DBS Group's acquisition of Hong Kong's Dao Heng Bank in April last year for a rich 3.2 times book value caused DBS's share price to plummet 10 percent (Institutional Investor, February 2002). The 50 times 2001 earnings that Singapore Telecommunications shelled out for Australia's Cable & Wireless Optus in March 2001 sent its share price tumbling 25 percent.

Investors don't dispute the government's assertion that Singapore's tiny market is near the saturation point and that major domestic companies have little alternative but to expand overseas. But they still object to the steep price paid for acquisitions that may not pay off for years and suggest that if the government wants to temper criticism, it should set clear targets for shareholder returns at government enterprises. One banking analyst proposes that Singapore follow the example of HSBC Holdings and set a target of doubling shareholder value every five years.

The holding company through which Singapore maintains stakes in government enterprises, Temasek Holdings, is planning to introduce benchmarks along these lines. "They are looking into setting clear perfor-mance benchmarks," says a government source. "They will set the benchmark, and they will then tell the management, 'Go and hit the benchmark. And if you don't, then why?'"

Successful entrepreneurs, of course, learn soon enough to pay attention to shareholders. , K.H.

Puttering with the national pension

So central is the Central Provident Fund to Singapore's economy that the Economic Review Committee set up to ensure the city-state's competitiveness (top story) is studying the 91.2-billion-Singapore-dollar ($50.6 billion) national pension system with an eye to reform. That should elicit a guarded hooray from the CPF's 2.9 million long-suffering members.

The fund does not adequately cater to the retirement income needs of a rapidly aging society. The proportion of the city-state's population over 65 is set to rise from 7.3 percent in 1999 to 18.9 percent by 2030. And the fear is that unless strong remedial measures are taken, the CPF's failings could sap Singapore's vitality and competitiveness.

Based on a defined-contribution scheme to which workers must contribute 20 percent of their income each year and employers an additional 16 percent, the CPF has produced abysmal investment returns over the years. The foremost private sector authority on the fund, Mukul Asher, head of the Public Policy Program at the National University of Singapore, calculates that compound annual real returns on CPF investable balances averaged an anemic 1.83 percent between 1983 and 2000, at a time when Singapore's GDP was surging at about 8 percent a year. (The CPF doesn't publish numbers on investment returns.)

Why such dismal returns? The vast majority of CPF funds must be invested in special floating-rate government bonds paying an average of the fixed-deposit and month-end flexible saving rates.

But even if the CPF had produced a somewhat more respectable investment return of 5 percent, the median Singapore family would still be S$17,395, or 41 percent, short of annual pension income, estimate analysts at ING Baring Securities (Singapore). They base their calculation on a pension income equivalent to 50 percent of preretirement earnings. Returns from CPF investments would have to rise to 8.1 percent per annum , or 5.6 percentage points above the 2.5 percent nominal interest rate currently offered on CPF accounts , for the median household to earn an adequate pension, according to ING figures.

Among the fund's shortcomings, says Singapore University's Asher, is "a lack of transparency and accountability, particularly in investment management." Indeed, the CPF is prevented by statute from disclosing its investment policies , even to Parliament.

Purely a pension scheme when it was founded in 1955, a decade before Singapore's independence, the CPF has taken on a grab-bag of functions: Participants can use their balances to buy public apartments as well as invest in mutual funds. The fund also provides medical coverage for members, who may have as much as 22 percent of their contributions channeled into a Medisave account that can be used to pay hospital bills and some outpatient fees.

The government "is constantly unhappy with the CPF because it serves too many objectives," acknowledges Minister of Trade and Industry George Yeo. He expects the review commission to recommend "resimplifying" the CPF, but how remains to be decided.

Senior Minister of State for Trade and Education Tharman Shanmugaratnam, who heads the commission subcommittee looking into the fund, indicates that after examining defined contribution pension systems in Hong Kong and Chile that use private fund management firms, the commission may seek to "graft some more of the features of a private pension fund scheme onto the CPF system."

The CPF already allows participants to invest a part of their balances in mutual funds, stocks and annuities. Currently, S$63.8 billion in balances that participants could be investing is idling in the fund's coffers. It is this money, together with S$25 billion in funds already withdrawn by participants for investment, that the government would likely target for management in a private pension fund.

Asher would like to see the retirement portion of the fund taken away from the CPF Board and invested instead through a new asset management organization. It should have an explicit mandate of fiduciary responsibility, an internationally accepted governance structure, and practice transparency, accountability and full disclosure, he says. Asher proposes that contributions of 10 to 15 percent of salaries be dedicated to the new retirement fund. The CPF Board, meanwhile, should continue to look after public housing, health care and other social welfare schemes, he says.

Still, he's pessimistic about the prospects for significant reform. "The CPF has become an integral part of social-economic-political management in Singapore," he notes. "There is, therefore, considerable resistance to any substantive changes." Nevertheless, he says, the government recognizes that its authority depends on fulfilling Singaporeans' material needs and that "it is by now apparent that the current pension arrangements are inadequate for providing financial security in old age."

Minister of Trade and Industry Yeo also emphasizes that the CPF is integral to Singapore's economy. By promoting home ownership, he points out, the fund gives Singaporeans a stake in the country and ties them to it. "The CPF is deep in the machine," he cautions. "You can't just tinker with it by itself. If you tinker with it, you affect every other part of the machine." Still, the CPF could use an overhaul. , K.H.

Lee Kuan Yew's honor roll of entrepreneurs

In a speech last February, Singapore Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew cited a raft of flourishing enterprises started by local businesspeople to show that Singapore can indeed nurture entrepreneurs, despite the government's propensity to be all-controlling in economic (and most other) matters. Lee's honor roll of 23 companies hints at the kind of vigorous smaller enterprises the city-state now wants to cultivate:

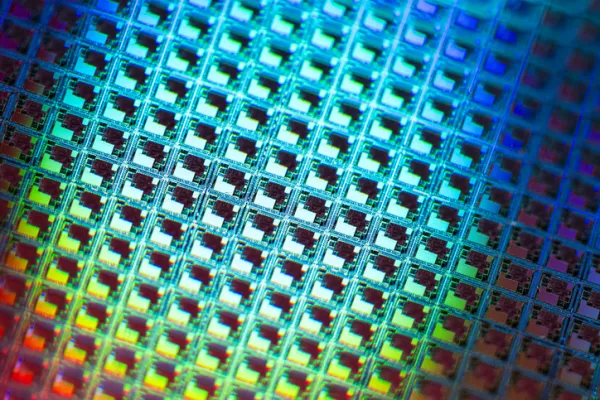

Advanced Systems Automation , Founded by Jimmy Chew in 1978, semiconductor-solutions provider Advanced Systems Automation was listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange in 1966. Today it is one of the top five producers worldwide of automold systems for semiconductors, with revenues of 200 million Singapore dollars ($115.5 million) in 2000.

AsiaTravel.com , Travel portal AsiaTravel.com, set up by Boh Tuang Poh in 1995, has been a hit with travelers looking for Asia's best hotel deals. The company now has ten offices across Asia and has been profitable virtually since its inception.

BeXcom , Yong Voon Fee's BeXcom provides technology for e-commerce and purports to be the first e-business system to integrate financial, logistics and authentication services into a global e-commerce infrastructure. Yong started BeXcom in 1996 after losing his life savings in a Silicon Valley start-up. Two years ago Yong won the Singapore Economic Development Board's Phoenix Award, which recognizes entrepreneurs who have overcome abject failure. "It's okay to lose a few battles as long as you win the war," he once told a local newspaper.

Chan Brothers International , Started in 1983, Anthony Chan's Chan Brothers International is one of Singapore's top travel agents, with a staff of more than 250.

Creative Technology , Probably Singapore's best known and most successful entrepreneur, Sim Wong Hoo founded Creative Technology in 1981 and grew it exponentially through sales of the SoundBlaster, which provides sound for personal computers. Today CT boasts 5,000 employees and revenues exceeding $1 billion.

Da Vinci Collection , Doris Phua founded retailer and exporter of lifestyle furniture Da Vinci Collection in 1978. The company now has a staff of 600 and annual sales in excess of S$140 million, with offices in Brunei, China and Malaysia. Last year Phua was the Association of Small and Medium Enterprises' Woman Entrepreneur of the Year.

DollarDEX , Financial portal DollarDEX, founded by former McKinsey & Co. consultant Richard Lai in late 1999, is a broker of insurance and mortgage loans as well as mutual funds. It has shaken up the funds market by slashing commissions to 2.5 percent or less.

Hong Leong Group , Kwek Leng Beng's Hong Leong Group is a powerful conglomerate, with interests in property, hotels and financial ser-vices. Its City Developments subsidiary is one of Singapore's top real estate companies. CDL Hotels has grown from six hotels in 1989 to 62 today. Kwek also owns New York's Plaza Hotel with Saudi Prince al-Waleed bin-Talal, as well as the 17-hotel Copthorne hotel chain in Europe. The Hong Leong group has annual sales exceeding $2.5 billion.

Hotel Properties , Property developer and hotelier Ong Beng Seng set up Hotel Properties in 1975 and now has 26 hotels in 11 countries, as well as food and beverage and retail operations. He is best known as the franchisee for Hard Rock Cafes in Asia and Hard Rock Hotels outside the U.S. Earlier this year he announced plans to build 12 Hard Rock Hotels worldwide by 2013. He also distributes Häagen-Dazs ice cream in Singapore and Malaysia.

Hyflux , A maker of water purification systems, Hyflux has established its brand name throughout Southeast Asia and now has operations in Hong Kong, Malaysia, South Africa and Taiwan. The company was founded in 1989 by Olivia Lum, an orphan from Malaysia. Afraid that her grandmother , who raised Lum with her gambling winnings from marathon mah-jongg sessions , would lose all her money, the young Lum determined to make a fortune. She moved to Singapore, worked her way through school and did just that. Hyflux went public this year.

Informatics Group , Founded by Wong Tai in 1983, Informatics Group in 1993 became the first private IT and business management training company to be listed on the Singapore exchange. Today it has a network of 38 training centers in 33 countries.

Interwoven , After a string of failed start-ups, Ong Peng Tsin hit the jackpot with Interwoven, launched in Singapore in 1995. This provider of infrastructure support for activities ranging from e-commerce to customer relationship management is now based in Irvine, California, and has been listed on Nasdaq since 1999. Ong retains his Singapore connection by serving on the Economic Review Committee.

MMI Holdings , Started by Teh Bong Lim in 1989, MMI Holdings provides precision engineering, contract manufacturing and factory automation services and is listed on the local exchange. Group revenues exceed S$165 million.

Nanofilm Technologies International , Three years ago Nanyang Technological University professor-turned-entrepreneur Shi Xu founded Nanofilm Technologies International. His patented process for coating hard disk drives won him Singapore's Innovation of the Year Award in 2001 and cornered the hard disk drive market.

OSIM International , Ron Sim founded OSIM International in 1980, and its motorized massage chairs are now a global brand. OSIM has 230 retail outlets around the world, including branches in China, Hong Kong and the U.S.

Raffles Medical Group , A provider of hospital and outpatient services, Raffles Medical Group was founded by Loo Choon Yong in 1976 and is listed on the Singapore exchange. Raffles now has more than 60 clinics in Singapore as well as a presence in Hong Kong and Indonesia.

Super Coffeemix Manufacturing , Teo Kee Bock's inspired idea back in 1987 of selling a three-in-one instant coffee mix , combining coffee, milk and sugar in one packet , propelled Super Coffeemix Manufacturing to swift success. It has branched out to other instant beverages and convenience foods and expanded its operations to China, Indonesia, Malaysia and Myanmar. The coffee mix sells in 30 countries.

System Access , Software solutions provider System Access was founded by Leslie Loh in 1983 and now has 350 staffers in eight offices in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East and the U.S.

Tee Yih Jia Food Manufacturing , Although Sam Goi had no knowledge of food production, that didn't stop him from founding Tee Yih Jia Food Manufacturing in 1977. Goi bought a small, labor-intensive manufacturer of spring rolls and used his engineering background to move it into automated production. The company now sells Asian snacks such as crepes, glutinous rice balls, samosas and roti prata in Asia, Europe, the Middle East and the U.S.

Thong Siek Food Industry , Lim Boon Chay has transformed Thong Siek Food Industry from the modest fishball-producing outfit that he started in 1976 into a $17 million export industry. Lim sells his cheese-flavored fishballs, spirulina-filled fishballs and crab sticks fortified with Omega 3 , considered good for health , in France, Germany, Sweden and the U.S.

Venture Manufacturing , In 1999 electronics manufacturer Venture Manufacturing was voted the most competitive high-end manufacturer in Asia in a newspaper survey. Set up by Wong Ngit Liong in 1984, it ranks among the world's top 15 electronics manufacturers by sales.

World Scientific Publishing Co. , Since 1980 Doreen Liu's World Scientific Publishing Co. has grown from two people to 130. It publishes scientific, technical and medical manuals, producing 32 journal titles and 300 books a year.

YCH Group , Starting in 1977 with a family trucking business, Robert Yap built a leading global logistics services provider, YCH Group, that specializes in global supply chain solutions. , K.H.