In July, Ireland was reeling from a flare-up of the European debt crisis. A fresh bailout package for Greece had failed to calm markets, and investors were rushing to sell bonds of other debt-laden countries. Yields on Irish ten-year government bonds surged to 14.1 percent, or 1,145 basis points more than comparable German obligations. Moody’s Investors Service underscored the gloom by downgrading Ireland’s debt one notch, to Ba1, a sub-investment-grade, or junk, rating. In that climate would anyone risk putting money into Ireland?

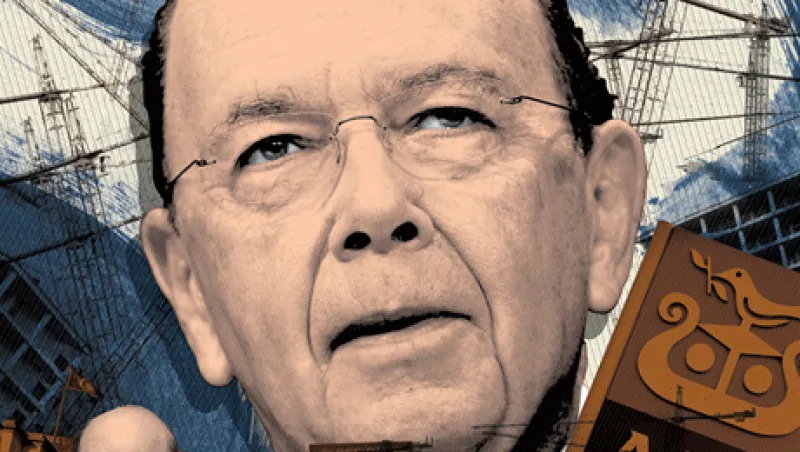

For Bank of Ireland, the outlook seemed dire. The bailed-out lender had been trying to raise capital from private investors for months, with little apparent success. Yet in late July the bank pulled off a coup, selling a 34.9 percent stake to a group of investors led by U.S. turnaround specialist Wilbur Ross Jr. and Canada’s Fairfax Financial Holdings for €1.12 billion ($1.6 billion), part of a broader, €4.8 billion capital-raising. It was a deal of huge moment: For the first time since the collapse of the country’s banking system in 2008, an Irish bank had been able to attract fresh private investment. The sale cut the state’s holding in Bank of Ireland from 36 percent to 15 percent.

One of two so-called pillar banks that the government is relying on to rebuild the banking sector and revive the economy, Bank of Ireland is now solidly in private hands and enjoying the best hopes of a turnaround in years. The bank narrowed its losses significantly in the first half of this year and is beginning to find funding from market sources rather than just the European Central Bank and other official bodies. It is carrying out a deleveraging plan and purging its balance sheet of bad real estate loans. Analysts believe the bank is on track to resume solid profitability in two years’ time.

“Bank of Ireland is stronger than the other Irish banks and has a powerful market position as one of the two pillar banks,” Ross tells Institutional Investor. “I’m not saying that this is the end of the problems facing the Irish banking system, but Bank of Ireland is recovering.”

As welcome as Ross’s vote of confidence was, Ireland and its banking system face a long and uncertain road to recovery. The country’s other pillar bank, Allied Irish Banks (AIB), remains in intensive care: The bank, 99.8 percent owned by the state, continues to suffer from mounting losses, loan-loss provisions and nonperforming loans. By its own admission, AIB can’t hope to raise private capital until 2012 at the earliest. The institution also has a leadership vacuum as it seeks to hire a new CEO.

That’s the good part of the industry — the two banks that are expected to survive and thrive in the future. Plenty of other wreckage is scattered across the financial landscape. Anglo Irish Bank Corp., once Ireland’s third-largest lender, is being wound down at great cost, unable to make it even after the injection of €29 billion of state money (see story, right). The property market, source of most of the industry’s problems, as it accounts for a majority of the toxic loans in the banking system, continues to see steadily falling prices.

Restoring the banks to health is critical to getting the Irish economy and the government’s finances back in shape. Reckless lending by the banks brought the economy crashing down in the financial crisis. The government’s decision to bail out the industry — guaranteeing bank liabilities to the tune of €400 billion, or twice the country’s GDP, and injecting €63 billion in capital — turned one of Europe’s healthiest public sector balance sheets into a basket case. The onetime Celtic Tiger, which enjoyed a surge of foreign investment in the 1990s and became one of the richest countries in the European Union, found itself locked out of the markets. ?That forced then–prime minister Brian Cowen to go to the EU and the International Monetary Fund for an €85 billion bailout last November.

Repairing the banking sector while maintaining fiscal discipline in accordance with the EU-IMF program is a difficult feat to pull off, especially at a time of sluggish economic growth. The program calls for the government to slash its deficit to less than 3 percent of GDP by 2015 from an expected 10 percent this year. To that end, the government is cutting spending this year by €4 billion, or 6 percent, and increasing income and gasoline taxes by €2 billion. Finance Minister Michael Noonan has warned that cuts in 2012 may be deeper than the program’s planned €3.6 billion. Experts from the European Commission, ECB and IMF, who visited Dublin in July to review the progress, said the government was on track to meet the plan’s targets. The officials also praised the way in which the banks were being recapitalized and deleveraged.

Prime Minister Enda Kenny, whose Fine Gael government swept to power in February 2011 by promising to renegotiate a bailout he called “a bad deal for Ireland,” got some additional help in July when EU leaders agreed to lower interest rates and lengthen maturities on loans to Ireland and Portugal as part of a package that included fresh bailout money for Greece. The EU’s new terms, which reduce rates on about €40 billion of loans to as low as 3.5 percent from about 6 percent previously, will save the Irish government nearly €1 billion a year in interest payments. “This is a material saving,” says Simon Barry, chief economist for Ireland at Ulster Bank in Dublin.

The breathing space bolsters Ireland’s chances of avoiding a second bailout in 2013 or 2014 — something that seemed almost certain only a few months ago — but doesn’t remove that prospect entirely. The EU and IMF loans are projected to cover the government’s needs through the end of 2013. Ireland is scheduled to dip into the debt markets next year as a trial run before resuming borrowing on a bigger scale in 2013. That’s not a sure thing. In August the yield on Irish ten-year bonds stood at about 9.5 percent, well below the high of 14 percent a few weeks earlier but still a long way from a sustainable level that would enable the government to tap the markets. “The spread will have to come down a long way” before Ireland can start raising money in the debt markets again, Patrick Honohan, governor of the Central Bank of Ireland, tells Institutional Investor.

The crunch point will come in January 2014, when Ireland is scheduled to repay €12 billion of debt and the national debt is projected to peak at more than €200 billion, or about 120 percent of GDP — a far cry from 2007, when debt was a mere 25 percent of GDP. The government will need to raise a total of €33 billion in 2014 and 2015 to cover its deficit and debt repayments. If the state can’t access the markets, it will have to turn again to the EU and IMF.

Although Moody’s cast doubt on Ireland’s ability to meet its targets, Standard & Poor’s in August reaffirmed Ireland’s investment-grade rating of BBB+ and said it believed the government would be able to return to the debt markets in 2013.

The economy, meanwhile, shows only a glimmer of recovery. Output, which plunged by 7 percent in 2009 and dipped a further 1 percent in 2010, has turned slightly positive. The central bank forecasts growth of 0.8 percent this year, rising to 2.2 percent by 2014. Unemployment stood at 14.3 percent at the end of July, off slightly from a December 2010 peak of 14.7 percent but well above the 4.5 percent that prevailed in July 2007, just before the outbreak of the financial crisis.

THE DEPTH OF IRELAND’S CRISIS TODAY is a mirror image of the excesses of the country’s property boom. Between 2002 and 2008, banks went on a lending binge, increasing their assets to €400 billion from €150 billion, according to a report earlier this year by a government-appointed commission on the banking collapse led by Peter Nyberg, a former Finnish regulator. Mortgages accounted for just more than half of the new loans; a big chunk of the rest were for commercial property. All that money pushed prices to unsustainable levels. Real commercial property values rose by 200 percent between 1995 and 2007, and residential values climbed 180 percent.

Property bubbles weren’t unique to Ireland, of course, but the scale of the problem dwarfed that of other countries. Irish property lending amounted to 147 percent of GDP at the end of 2008, compared with just under 106 percent in the U.K. Banks lent so freely that money poured out of the country. Polite Dublin society marveled at how even its cleaners were able to buy second homes in Spain and Turkey. When the bubble burst, it did so with a vengeance. By the middle of this year, commercial property prices had fallen 63 percent from their peak levels in 2007 and residential prices were off 41 percent, according to real estate firm Jones Lang LaSalle.

The crash effectively brought down all six domestic banks. To keep them afloat, the Irish central bank and the ECB provided massive liquidity: The amount peaked at €187 billion in February and declined to €155 billion in July. The government has financed five major recapitalizations, each one purportedly the last, since 2009. It also created a so-called bad bank, the National Asset Management Agency, which has taken €71 billion of the worst assets off the banks’ books. Even so, at least three of the six banks are being wound down or consolidated.

The future rests with Bank of Ireland and AlB, which the authorities consider too important to fail because they control 60 percent of the domestic retail market. “The Anglo Irish brand and customer relationships were irreparably damaged, whereas, despite the difficulties they’ve had, Bank of Ireland and AIB are the backbone of the economy and a majority of the population of Ireland has dealings with them,” says central banker Honohan. “They have to work through their financial restructurings, but I think their health will improve now that they have been recapitalized and as further deleveraging takes place.”

It’s little surprise that Bank of Ireland is the first institution to regain access to private capital. The bank didn’t expand property lending to the same extent its rivals did and as a result has suffered fewer loan losses and required less government support. After gains of €167 million on disposals and a 22 percent drop in loan write-downs, the bank’s underlying pretax loss declined to €723 million in the first half of this year from €1.32 billion a year earlier.

The state has injected €3.5 billion into the bank since January 2009 in exchange for a 36 percent stake. The €4.8 billion raising in July reduced that stake to 15 percent.

One key reason Bank of Ireland was able to attract outside investors is its diversification. At the end of June, fully 46 percent of its €112 billion loan book was in the U.K., compared with 48 percent in Ireland. “We see this as positive because the U.K. economy is in better shape” than Ireland’s, says investor Ross. The bank had taken write-downs on only 0.5 percent of its €30 billion in U.K. residential mortgages at the end of June, compared with 3.8 percent of its €28 billion Irish mortgage book.

Those U.K. mortgages are also helping the bank obtain funding. In June, Bank of Ireland raised €2.9 billion in short-term loans secured by its U.K. mortgages from two unidentified international banks. The money didn’t come cheaply: The bank is paying 2.65 percentage points over three-month Euribor for funds with an average maturity of a little more than two years. Still, the bank managed to pull off the deal, at a time when the Irish government has yet to reenter the capital markets. “You wouldn’t normally expect one of the banks to return to the markets before the sovereign, and it’s still unlikely that Bank of Ireland will be able to do anything more than these secured trades for some time to come,” says Stephen Lyons, a credit analyst at Davy Stockbrokers in Dublin. The bank says it plans to seek further secured loans later this year.

Bank of Ireland is also making good progress on deleveraging and expects to exceed its targets under a restructuring plan agreed upon by the EU, IMF and Irish authorities in March. The loan book had declined to €112 billion at the end of June from €119 billion at the end of 2010, while the loans-to-deposits ratio fell to 164 percent from 175 percent. In August the bank sold a €1.4 billion portfolio of U.S. commercial real estate loans to Wells Fargo & Co. It plans to dispose of an additional €10 billion by the end of 2013 to reduce its loans-to-deposits ratio to 122.5 percent or lower, as required. The bank has pledged to cut its loan book to €90 billion or less and reduce its loans-to-deposits ratio to less than 120 percent by the end of 2014.

Those improving trends set the stage for the bank’s recent capital-raising. The central bank and Department of Finance had ordered the bank to raise at least €4 billion in capital by the end of July, following a stress test carried out earlier this year by BlackRock Solutions and endorsed by EU and IMF officials in March. For months it was unclear whether Bank of Ireland would succeed; if it hadn’t, the government would have been forced to pony up capital. But with just a few days left before the deadline, the bank announced a three-part deal to raise a total of €4.2 billion and lift its core tier-1 ratio to 15 percent of risk-weighted assets, double the minimum level set by the new Basel III accord.

Under the deal, Bank of Ireland raised a total of €3.8 billion through an 18-for-5 rights issue priced at 10 cents a share and an exchange of €1.9 billion of subordinated debt for equity priced at 10 to 20 cents on the euro. More important, the bank arranged the sale of a portion of the state’s holding to a group of foreign investors, led by Ross and Fairfax, for €1.12 billion. WL Ross & Co., the billionaire investor’s New York–based private equity firm, and Toronto-based Fairfax each took a 9.9 percent stake. Other prominent investors participating in the deal included mutual fund giants Fidelity Investments and Capital Group Cos., and Kennedy Wilson Holdings, a Beverly Hills, California–based real estate investment firm.

The participation of such blue-chip investors provided a much-needed boost for the industry’s rebuilding efforts, and for Ireland’s economic prospects. “We shouldn’t underestimate the significance of hard private sector cash,” says Ulster Bank’s Barry. “It shows a willingness to reengage with the Irish story.”

The government and the bank had been courting private equity players for at least a year, after giving up hope of luring an international bank as an acquirer. Firms including Carlyle Group and Blackstone Group had shown some interest, but only with big conditions attached. “Private equity firms wanted complex structures that included downside protection, a considerable degree of risk-sharing with the Irish government,” says Mark Spain, a director at IBI Corporate Finance in Dublin who advised on the deal and has worked with the bank since 2008. “This wasn’t acceptable to the government.”

The participation of Ross and others had a positive effect on Bank of Ireland’s rights issue. Advisers had been projecting that as few as 20 percent of existing holders would exercise their rights and buy new shares, but a late surge of interest among retail investors boosted the final take-up rate to 60 percent. The participants included Harris Associates, a Chicago-based activist investor that now has a stake of about 4 percent in the bank.

Eamonn Hughes, a banking analyst at Goodbody Stockbrokers in Dublin and a consistent bear on Bank of Ireland, welcomed the results of the exercise. “It is a sign of confidence in the bank and in Ireland,” he says. Still, Hughes is tempering his optimism, maintaining a target of 8.5 cents on the bank’s shares through 2012, below the 10-cent price paid by the investor group. The shares have traded between 9 cents and 11 cents recently. “Economic prospects have to improve before the bank’s prospects really improve,” he says.

Bank of Ireland has plenty of work to do to justify the optimism of its new investors. First, it must increase deposits to stabilize its funding base. Deposits had fallen to €65 billion at the end of 2010 from €85 billion a year earlier and remained flat in the first half of this year. The bank needs to boost deposits if it hopes to reduce its reliance on ECB and Central Bank of Ireland liquidity facilities. Bank of Ireland was drawing €29 billion from those official sources at the end of June, down just €2 billion from the end of 2010.

Longer term the bank will need to complete its deleveraging program and restore profitability to regain access to wholesale funding markets. Most analysts, such as Karl Goggin at NCB Stockbrokers in Dublin, believe the bank won’t break even until 2013 at the earliest. Last month Asheefa Sarangi, an analyst at Royal Bank of Scotland, predicted that there would be “minimal value creation for shareholders before 2016.”

Bank of Ireland’s challenges pale beside those of the country’s other pillar bank, Allied Irish. Once the biggest Irish lender, with a market capitalization of some €20 billion, AIB is now 99.8 percent owned by the state after the injection of €25 billion of public money since 2009. Still, the bank’s results continue to deteriorate. Irish commercial and residential real estate loans make up €86 billion of its €127 billion in assets. The bank took €2.6 billion of impairments, or write-downs, on those loans in the first half of 2011, up from €2 billion a year earlier. Loan-loss provisions rose to €2.9 billion from €2.26 billion a year earlier. Fully 34 percent of the bank’s total loans were nonperforming, up from 29 percent at the end of 2010. As a result, the bank posted an underlying loss, excluding gains on disposals and its bond buyback, of €2.6 billion in the first half.

Analysts decry the leadership vacuum at the bank. Eugene Sheehy, who was CEO during the crisis, resigned in April 2009 after AIB was forced to issue equity — something he had said he would rather die than do. His successor, former acting managing director Colm Doherty, was pushed out in September 2010 by the government after he too failed to get on top of the bank’s capital needs. The bank is being led for now by executive chairman David Hodgkinson, an Englishman and a former COO of HSBC Holdings. He has expressed hope that AIB might attract private investors next year.

Following AIB’s stress test earlier this year, authorities ordered the bank to raise €14 billion in capital, but in contrast to Bank of Ireland, there was no participation by private investors beyond an obligatory, €1.6 billion debt-for-equity exchange with junior bondholders. The government underwrote the rest of the funds, with the National Pensions Reserve Fund buying €5 billion worth of shares priced at 1 cent each and the Department of Finance buying €1.6 billion of contingent capital notes. The department injected an additional €6 billion of capital for no equity consideration. The exercise boosted the bank’s core tier-1 capital ratio to 9.9 percent.

AIB reduced its assets by €8.3 billion in the first half of this year, mostly through repayments and the sale of €1.5 billion of loans in the U.S. and Europe. Those moves helped lower its loans-to-deposits ratio to 143 percent from 165 percent. As part of its restructuring, the bank plans to shrink its asset base by a further €19 billion, or 22 percent, by the end of 2013 and slash its loans-to-deposits ratio to 122.5 percent or lower. Although most of the bank’s loans are in Ireland, AIB is seeking to dispose of €1.5 billion in U.S. real estate loans. Notwithstanding those efforts, it remains unclear when AIB can return to profitability and attract private investors.

As the two banks continue on their long path to recovery, Ireland’s banking regulators are drawing lessons from the crisis and restructuring themselves in a bid to prevent future calamities.

The Nyberg report criticized the Financial Services Regulatory Authority, the former banking supervisory body, for failing to force banks to improve risk management and tighten lending practices despite overwhelming evidence of the need for action as early as 2004. The report also said the central bank had failed to properly oversee the supervisory authority. To address those problems, the government has moved banking supervision inside the central bank, placing it under the direction of a financial regulator who reports directly to governor Honohan. The government last year appointed Matthew Elderfield, an Englishman who formerly headed the Bermuda Monetary Authority, as the regulator. “Now everyone is communicating with each other, and we are constantly improving and expanding the system,” says Honohan. “We didn’t have enough people before the crisis, but we’re recruiting an extra 200 people at the central bank this year.”

As part of the restructuring plan — and to help revive the economy — the government has ordered the banks to provide €30 billion of new lending to the domestic market over the next three years. The Department of Finance believes this should be enough to ensure that growth is in line with forecasts. John Bruton, the former prime minister who is now chairman of Dublin’s International Financial Services Centre, says: “I don’t think there is a problem with the availability of finance. If there is a problem, it’s a lack of demand.”

A revival of confidence among consumers and businesses would do wonders to stimulate demand. In that respect, the capital-raising by Bank of Ireland and the faith of its new investors provide the best news the country has had in some time.

“I’m keen on Ireland as a long-term investment,” says an enthusiastic Wilbur Ross. “It doesn’t need structural reform like the ‘Club Med’ countries of southern Europe because it had been functioning well until the banks got out of control. The government is determined to cut back on spending.”

The Irish can only hope that Ross’s optimism proves infectious. • •