While the West struggles to emerge from economic mire, Turkey’s leaders brim with confidence. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan showed supreme political self-assurance when he ordered the February arrest of nearly 50 army officers, alleging a coup plot in a country in which four governments have been overthrown since 1960. Economic ministers in Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) are showing strength in other ways.

Ali Babacan, the deputy prime minister who has captained Turkey’s economic makeover since the AKP came to power in 2002, took a schoolmasterish tone in an address to the recent gathering of European chambers of commerce in Istanbul, lamenting his EU neighbors’ lack of any “concrete program for countries that indicates how they fight budget deficits.” Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek announced the nation didn’t need a standby loan from the International Monetary Fund, a frequent source of government funding in the past. “We told the fund that if they support our program they could prove useful,” he tells Institutional Investor. “But we have gotten through the worst of the crisis without external assistance.”

Such a position seems justified. Turkey’s economy, notably its financial system, is proving one of the most resilient in Eurasia. Not one of the country’s 49 banks needed a bailout to survive the global downturn. Capital adequacy ratios average near 20 percent, and conservative management is enforced by aggressive regulation. Partly as a result, Turkey shows signs of a vibrant V-shaped climb out of recession. Output rebounded by 6.7 percent in the third quarter of last year compared with the previous three months, and another 2.3 percent quarter-on-quarter growth was added in the fourth quarter. “Recovery is under way,” Simsek says.

Turkey’s Cinderella story has not reached its fairy-tale ending, though. One reason the banks are solid is that they do not lend much in an economy in which many transactions take place off the books. Loans total a mere 36 percent of gross domestic product, compared with 52 percent in Central Europe and 128 percent in the Eurozone, according to Istanbul-based Garanti Bank. Economic contraction was severe in Turkey while it lasted: Annual GDP shrank by 5.8 percent in 2009, worse than the EU’s 4 percent average. Unemployment remains stubbornly high, partly, Erdogan’s critics say, because he underestimated the impact of the global crisis on Turkey. “They ignored unemployment and now they will pay the price,” says Faik Oztrak, a former Treasury undersecretary who sits in parliament for the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP).

AKP’s legislative majority indeed looks vulnerable in the 2011 elections. Polls indicate the party’s support has gone from the 47 percent it won at the last vote in 2007 to something above 30 percent. Istanbul financiers feel uneasy with the AKP’s Islamic roots and theocratic moves such as the AKP’s purging of professors who honored Charles Darwin at the venerable Istanbul University. But bankers are more afraid of Turkey returning to its tradition of weak coalition governments that can never refuse any special-interest demands. “The pension age in this country before AKP took power was 43 for men and 38 for women,” says Yarkin Sebeci, chief economist for JP Morgan Chase & Co. in Istanbul. “That’s incredible, but that’s what coalition government got us.” Erdogan’s party has pushed retirement thresholds up to age 60 and 56, respectively.

This country of 73 million was hammered during the first crisis of the new century, the downturn of 2000–2001. Twin currency and banking crises shrank GDP by more than 7 percent in 2001. The Turkish lira lost half its value.

Bad government and bad finance fed off each other in those grim days. A spendthrift state stoked inflation that reached 65 percent annually in 2000. The Turkish Central Bank, encouraged by the IMF, tried and failed to defend a pegged exchange rate. Turkish banking was anarchic and in some cases corrupt, dominated by state institutions that loaned to the politically connected and by oligarch banks that served as cash boxes for their owners’ industrial projects. Both types were fueled by foreign hot money in the late 1990s. The system was devastated when the lira crashed. Nonperforming loans reached 32 percent and more than one third of the country’s banks went out of business.

Riding a promise of reform, the AKP was just 15 months old when it swept into power in November 2002, born of a breakaway pro-market, pro-European faction of the older Islamic Virtue Party. A shift in election law requiring 10 percent of the vote for parties to enter Parliament allowed the AKP to win Turkey’s first outright majority in decades.

It used the power to slash public spending and privatize major state enterprises, from steelmaker Erdemir to tobacco and alcohol giant Tekel. Obeying the strictures of two IMF adjustment programs, Turkey ran large primary budget surpluses for six years leading to the 2008–’09 world crisis, reducing the national debt from 67 percent of GDP to 43 percent. The independent central bank kept money tight too, imposing some of the world’s highest real interest rates throughout the postcrisis years. Inflation plummeted to below 10 percent by 2005 and has remained near there since. The lira appreciated, and the government revalued the currency. With a favorable external wind, Turkey averaged more than 6 percent annual economic growth from 2003–’08.

Turkey’s second great financial achievement was to radically overhaul its banking system under the hawkish eye of the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency, an autonomous body founded in 2001. “We have four or five full-time BRSA auditors who work on the 16th floor of our building and file weekly reports,” says Handin Saygin, chief of investor relations at Garanti Bank, Turkey’s third-largest. Foreign-currency lending and unhedged forex borrowing are forbidden. Turkish banks take a healthy 60 percent–plus of funding from deposits.

Banks have flourished, not least because BRSA has limited competition, granting no new licenses since its inception. Hale Tunaboylu, director of strategic planning at No. 5 bank Yapi Kredi, is pleased to call its core credit-card business “oligopolistic,” meaning it is more selective than similar programs at Western banks and hence carries lower risk. Yapi and Garanti dominate the market, allowing them to charge interest above 30 percent annually even as central bank rates fell to single digits last year. Foreign banks seeking a share of such bounty have been forced to partner with Turkish grandees that survived the 2000–’01 tsunami. UniCredit and Koc Group jointly control 80 percent of Yapi Kredi. Citibank owns 20 percent of No. 4 Akbank as a junior partner to H.O. Sabanci Holding, a financial conglomerate. “Banks are the shining star in Turkey,” says Levent Topcu, director of financial institutions at Fitch Ratings in Istanbul.

The banks and the Turkish state have lent strength to each other through the shock of the past 18 months. The central bank gave financiers a big lift with a reduction of interest rates from 16.75 percent in September 2008 to 6.5 percent today. That meant continual enhancement of the spread between banks’ borrowing and loan books. “This was the government’s present to the banks,” Yapi’s Tunaboylu says. The BRSA helped additionally with a looser definition of NPLs that kept this category to a manageable 5.2 percent systemwide. Under previous regulations it might have reached 8 percent, says Gunduz Findikcioglu, chief economist at development bank TSKB.

The stimuli worked: Profits at Turkish banks actually rose almost 50 percent in 2009, and some dabbled as capital exporters. “This is the first time in history that foreign banks are knocking on our doors for money,” Garanti’s Saygin says.

The banks’ deep pockets enabled Turkey’s government to weather the crisis without fresh foreign borrowing, or tapping the IMF. Dwindling tax receipts and pump-priming expenditures led to a budget hole last year amounting to 6.6 percent of GDP. But Ankara closed the gap with domestic bond issues and continued to cut foreign debt, making Turkey one of the few countries to win sovereign credit upgrades during the recession. The latest reevaluation came in February from Standard & Poor’s, which raised Turkey to two notches below investment grade with a positive outlook. Equity investors have been bullish too. The Istanbul Stock Exchange’s benchmark XU 100 index more than doubled in the 12-month period to March 2010. “The EU’s business sector has no doubt that Turkey is a key part of the EU’s global competitiveness,” says Tibor Varadi, deputy head of the European Commission’s delegation in Ankara.

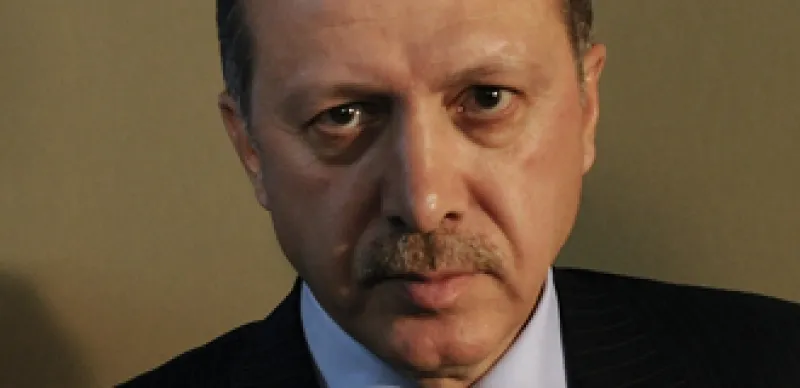

Prime Minister Erdogan, 56, understands the struggles of the average Turk. Raised in Istanbul’s tough Kasimpasa district, he peddled sesame buns on the streets as a teenager to help support his family. He studied business administration at the Aksaray School of Economics and Commercial Sciences and reached national prominence in the 1990s as a can-do mayor of Istanbul, improving trash pickup and running new bus routes to the city’s poor neighborhoods.

Yet the AKP leader has had trouble focusing on economics since his reelection in 2007, preferring to take on such issues as the easing of restrictions on Turkey’s Kurdish minority or enhancing ties with Eastern neighbors such as Iraq and Syria. “I think [deputy prime minister] Babacan, who is running the economy, has a hard time communicating with Erdogan,” says Murat Ucer, who heads the Istanbul office of U.S.-based Global Source Partners, which offers consulting services on local economics and politics.

In his interview with II, Finance Minister Simsek outlines stimulus measures the government took to offset a drop in exports last year as demand plummeted from Turkey’s primary market, the EU. The state offered to pay a share of the wages of workers threatened with layoffs, granted long social security tax holidays for new hires, pared corporate tax to as low as 2 percent on earnings from new investments and poured cash into infrastructure. Turkey actually created 400,000 jobs last year, says Simsek, who was Merrill Lynch’s chief emerging Europe economist in London for seven years. But natural workforce growth of 500,000 in a country where the median age is less than 28 has pushed unemployment up to 13 percent from 10 percent.

Financial observers also regret that Turkey didn’t borrow money from the IMF when it could. Ankara’s last adjustment program expired in May 2008, and the fund was prepared to offer a loan in the billions when the crisis hit that autumn. Turkey could have used the extra funds to increase stimulus spending and reduce domestic borrowing, in theory leaving banks more funds for the private sector, where lending slumped by 7 percent last year. “This is not the old IMF with its tough conditionality,” says TSKB’s Findikcioglu. “Why not take the money and run?”

Instead, Erdogan and his ministers played a game of bait and switch, repeatedly announcing that a fund accord was imminent when Turkey’s bonds or currency looked stressed, then reverting to a stance against foreign handouts when market conditions improved. “They are manipulating the market by talking up an IMF deal whenever the Treasury has very high redemptions to meet,” says opposition legislator Oztrak.

Looking ahead, observers say Erdogan has yet to voice a clear strategic vision for moving Turkey out of underdevelopment. The country is richer than it was eight years ago, but poorer than the worst-off EU members. Turkish GDP per capita on a purchasing power basis is $11,200, according to the most recent CIA World Fact Book. That compares with $12,600 in Bulgaria, $17,800 in Poland and $32,100 in crisis-beset Greece.

Moreover, Turkish unemployment rose even in the boom years. Job creation failed to keep pace with new job seekers. Simsek is convinced lagging employment is linked to lagging education. The average Turkish five-year-old today can expect about 13 years of full-time schooling, compared to 14 years in Mexico and 17 in the Czech Republic, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The country has effectively moved up the value chain from farm products and textiles to medium-tech exports like cars and ships but produces little in brain-intensive sectors such as information technology or pharmaceuticals.

On the political side, Erdogan has taken some bold steps: meeting the head of the main (outlawed) Kurdish political party last year and helping drive out the longtime leader of Turkish-controlled Cyprus in 2004. But he’s also made some decisions that seem less praiseworthy, such as the crackdown on academics honoring Darwin or questionable tax-evasion fines levied against opposition-linked Dogan Media Group last year.

Economically, Turkey needs to reform small to medium-size private business and government bureaucracy with the same energy it focused on banking and state enterprise. Highly adaptable and entrepreneurial small businesses have always been Turkey’s lifeblood. They showed their smarts in the latest crisis by shifting commerce from struggling European customers to more free-spending prospects in the Middle East and North Africa. “The EU’s share of exports shrank from 55 to 47 percent in one year,” says Ulgen of Istanbul Economics. “That’s quite an achievement.”

But having half the economy beyond the reach of taxation or, for the most part, formal credit limits the possibilities for Turkey’s army of family firms to consolidate or diversify — and forces unhealthy contortions on how the state raises and redistributes wealth. Turkey’s government has to tax what it can find, which means whopping levies on consumer items like gasoline (pump prices are the highest in Europe) and cell-phone service. The country raises twice as much revenue from these indirect taxes, which disproportionately punish poorer users, as from direct corporate and income taxes, which take more from the rich. The norm in highly developed countries is exactly the opposite. Partly as a result, Turkey has one of the least equitable income distributions in the 30-member OECD, along with Mexico and Portugal.

One reason so many Turkish businesses keep a low profile is the perception that government is too heavy-handed. A recent World Bank survey of business in 29 emerging markets from Central Europe to Central Asia ranked Turkey’s managers first in the unhappy category of most time spent coping with regulation. Regulatory matters consume 27 percent of senior management time in Turkey.

While an AKP in power for another four years gives bankers pause, an alternative government with a return to loose budget controls and massive foreign borrowing has no appeal. “A [non-AKP] coalition would be an economic disaster,” says economist Findikcioglu.