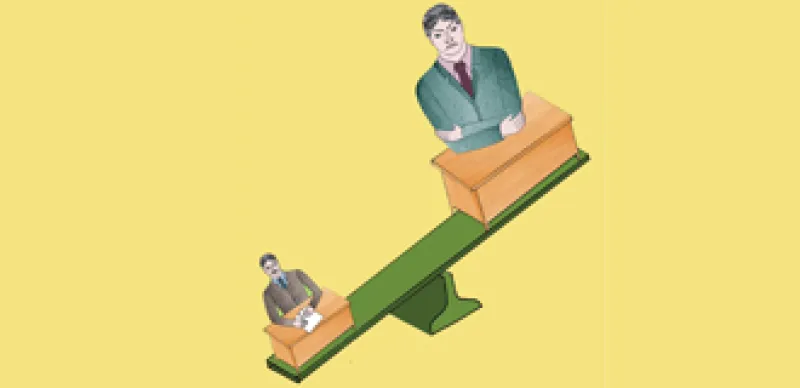

BlackRock CEO Laurence Fink set an aggressive tone for the asset management industry last December when he inked a $15.2 billion deal to acquire San Francisco–based Barclays Global Investors. Overnight, BlackRock became a $3.3 trillion asset manager — the world’s largest.

Since then money managers have been spending a lot of time searching out potential acquisition targets, while keeping an eye out for who may come courting them. After all, when it comes to economies of scale and building strong marketing, sales and technology arsenals in this challenging post–Great Recession era, big is better, right?

Maybe not. Many industry experts say larger asset managers don’t always deliver top-notch returns or — perhaps more importantly — the best customization of products and service. For example, in a 2007 article in Institutional Investor’s Journal of Investing, Ted Krum, senior investment program manager for Northern Trust Global Advisors, found that 40 percent of the core U.S. equity funds in the top performance quartile were run by firms managing less than $2 billion.

In light of that success, institutional investors have been taking advantage of the hundreds of boutique investment managers, attracted by their agility and client focus. “Almost everyone in the investment industry will acknowledge that investment products are best produced in a boutique setting,” says Paul Greenwood, a co-founder of Seattle-based Northern Lights Ventures, a multiboutique asset management group.

Yet just as investors are gravitating to boutique money managers, it has become tougher for these smaller firms to get off the ground — and to hang onto their independence.

The financial crisis of 2008–’09 has prompted institutional investors to demand that the smaller firms they work with prove that they are viable long-term business concerns with bulletproof (read, expensive) infrastructure and systems in place for regulatory compliance and fraud detection. “It’s not as easy anymore as two smart people getting together, discussing ideas and putting them into action,” says Chris McIsaac, head of Vanguard Group’s portfolio review department, which oversees subadvisers. “Firms need infrastructure, the ability to manage daily operations and satisfy clients’ compliance and regulatory needs.”

The financial reform legislation recently signed into law by President Barack Obama, while primarily aimed at large banks and other major financial institutions, also puts pressure on investment advisers to ramp up infrastructure needed to comply with the new rules.

Indeed, the barriers to entry that new, smaller asset managers face are more daunting than ever. “It used to be that you start out on your own, move to Connecticut and say ‘I’m here!’ But those were the good old days,” says Mitchell Harris, interim head of $1 trillion-in-assets BNY Mellon Asset Management, whose business model is to provide distribution and other support to 19 investment shops under the BNY Mellon brand. “Technology, reporting, regulatory requirements and risk management all make it challenging for small firms.” Brian Casey, president and CEO of $8.2 billion-in-assets, Dallas-based Westwood Holdings Group, concurs: “I will tell you that working with bigger clients, they want to spend 20 to 30 percent of the time on risk management and compliance. Five years ago that was an afterthought.”

Increased regulation, scrutiny from investors and an uncertain market environment are conspiring against boutiques, and the pressure is forcing some of them to look for an exit. “There is interest on the part of independent firms to get some deals done,” says Seth Brennan, co-founder of Boston-based Lincoln Peak Capital Management, which invests in asset managers. “Margins, while better than in 2008, are still not back to where they were in 2007. We’re seeing that people are recognizing that the world is a more volatile and dangerous place. The businesses are more fragile, and some owners want to take some chips off the table, particularly before taxes go up.”

Despite these challenges, many boutique asset managers are vowing to ride out the storm, confident that their performance and client service records will continue to impress. Payden & Rygel managing principal James Sarni says his firm “is the right size — meaning it is large enough to command respect in the market and service its clients, but not so big that it becomes less flexible and nimble in reacting to changing markets.” He could be right. Payden, a Los Angeles–based fixed-income specialist, went from $48 billion in assets in 2008 to $50 billion in 2009, and by the end of June of this year it had $55 billion.

Small firms outperform for some compelling reasons. For one, portfolio managers overseeing small pools of money can buy and sell securities with little impact on the price. When a portfolio manager with a huge block of a security — even in large, liquid stocks — makes a move to sell, the manager can often significantly drive down the price in the process. The same thing happens in reverse when buying.

Northern Lights’ Greenwood says an advantage also lies in how organizations work — in particular, something he calls “insight slippage.” This is when large bureaucracies and convoluted processes within a firm impede unique insights that a portfolio manager or analyst may have. What’s more, large firms are increasingly clamping down on rock-star portfolio managers. Although they can add significantly to a firm’s cachet, they are also a threat because they can walk out the door and take high-profile clients with them.

“The institutionalization of the process, while sometimes beneficial, often results in the dumbing down of the investment products and the considerable loss of insight,” says Greenwood. The longer an investment product has been around, the fewer chances the portfolio manager is taking. Larger firms are working to preserve the existing pool of assets, while smaller shops are focused on generating fabulous returns to attract clients.

Small firms appreciate star portfolio managers who execute ideas directly. These shops also tend to excel at aligning the interests of portfolio managers and clients. “Employee ownership is the single most important reason why small funds outperform,” says Sarah Ketterer, CEO of Causeway Capital Management in Los Angeles. Smaller firms can offer significant direct equity stakes to their talented portfolio managers and others who have a role in deciding which investments to buy. Investment research firm Morningstar rates asset managers on how much skin they have in the game — that is, how much of their own money they have invested in their funds and how much equity participation they have in their businesses.

Northern Lights, which allows asset managers to retain their independence, recognizes the value of these incentives, says Greenwood. The firm makes minority investments in its asset managers because it believes owners need to retain control of their businesses to deliver solid returns in the long term.

Indeed, maybe smaller is better.