World Bank Seeks Private Investment for Climate Change Fund

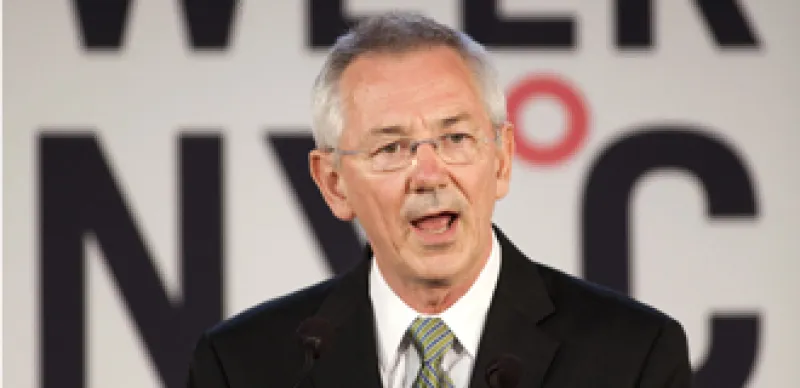

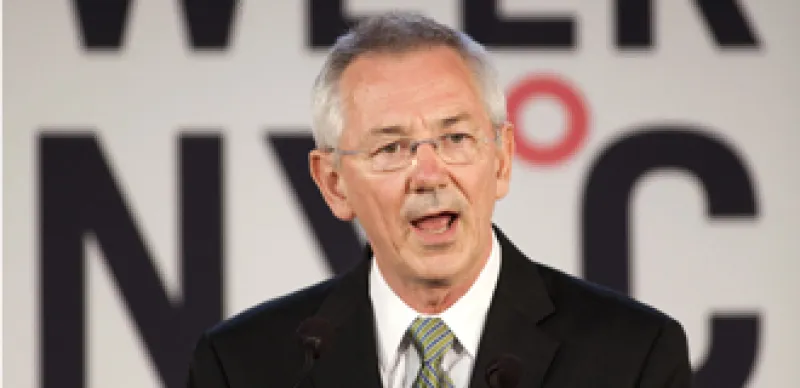

Andrew Steer, the World Bank’s Special Envoy on Climate Change, believes “we can’t insure away the problem” of global climate change. But, he says, involvement from private and public investors willing to employ modern financial techniques can make all the difference.

Maureen Nevin Duffy

November 1, 2010