The worldwide economic boom was in full swing in September 2006 when the International Monetary Fund dared to issue a note of warning at its annual meeting in Singapore. The U.S. could experience a “rapid weakening” of its housing market, IMF economists cautioned in the organization’s Global Financial Stability Report. Financial markets might be vulnerable after years of declining risk premiums and volatility, they added, citing in particular “the potential for illiquidity to emerge in response to unexpected stress in markets for new and complex financial instruments, such as structured-credit products.”

The great and the good of global finance barely paused to acknowledge the report before resuming their furious dealmaking at the meeting. But the start of the subprime meltdown, and the ensuing U.S. and global recessions, were just months away.

The Fund may have been ignored three years ago, but today the agency is enjoying newfound respect — and clout. Leaders of the Group of 20 nations agreed in April to triple the IMF’s lending resources, to $1 trillion, to help contain the crisis. And in seemingly belated recognition of the Fund’s earlier prescience, they mandated the IMF to work with the Financial Stability Board, a Basel-based forum of world regulators, to provide early warnings of economic and financial risks and policy advice on how to avoid them.

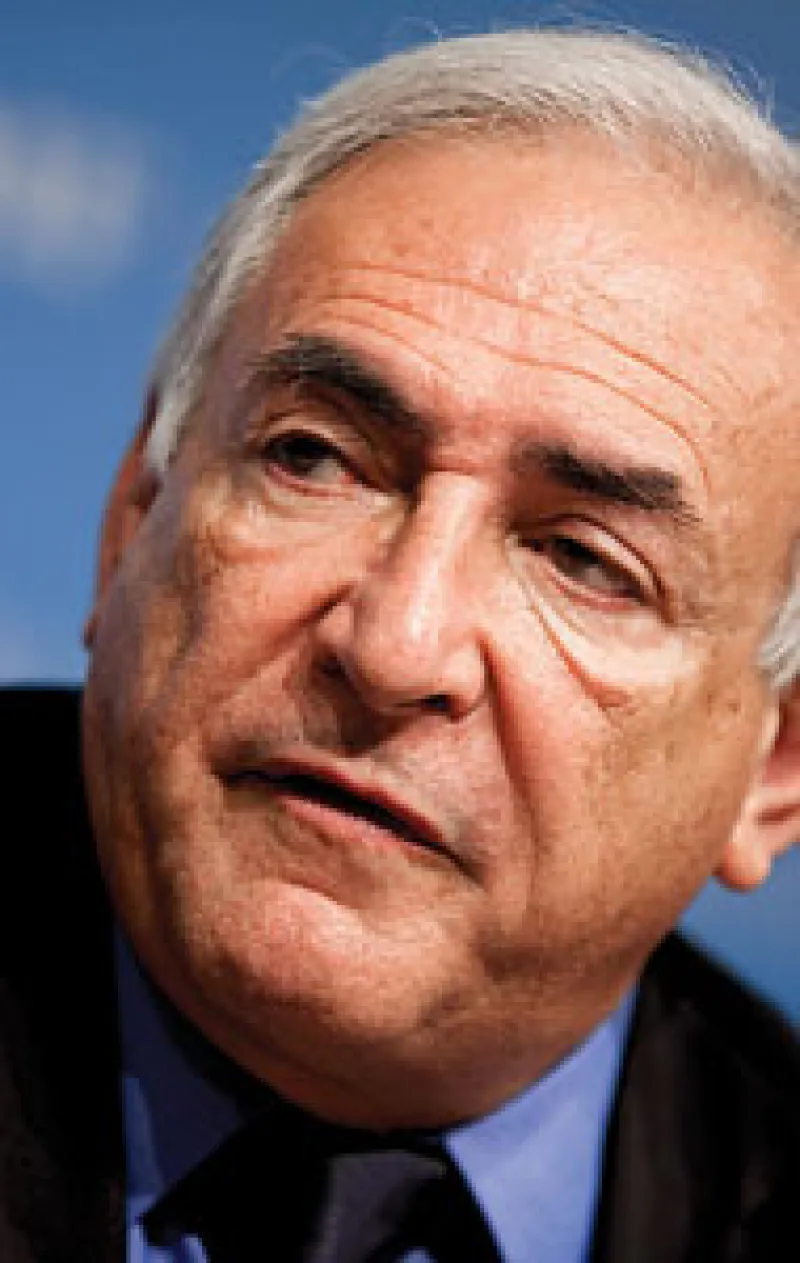

The Fund’s fortunes always wax in times of crisis, but managing director Dominique Strauss-Kahn has been particularly skillful in seizing the moment — and forging a close partnership with the U.S., his biggest shareholder. At the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2008, Strauss-Kahn, a former French Finance minister, defied decades of IMF fiscal orthodoxy and urged governments to adopt stimulus programs to cushion against the fallout from the crisis. The bold call impressed Lawrence Summers, who shared the Davos stage with Strauss-Kahn. One year later, Summers helped draft a $787 billion stimulus package as President Barack Obama’s top economic adviser.

Ahead of the G-20 meeting in London in April, Strauss-Kahn surprised some EU governments by winning strong backing from the U.S., a frequent laggard in contributing to multilateral institutions, in its quest for extra resources. Obama even won congressional approval for a U.S. contribution of $100 billion to the Fund, well before European governments started chipping in similar amounts. “It was a way of saying, ‘We’re back and playing a leadership role in the world,’” notes Edwin Truman, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, who worked on the IMF package while doing a brief stint at the U.S. Treasury earlier this year.

The Fund has long experience in handling financial crises around the world and deep ranks of top-flight economic analysts. “The need for an institution like this one is now apparent to everybody,” Strauss-Kahn told Institutional Investor in a recent interview. “No other institution is working at the corner of Main Street and Wall Street.”

Strauss-Kahn has also expanded the Fund’s tool kit. He won board approval in March for a new flexible credit line, under which countries with sound economic fundamentals can obtain borrowing lines to ward off market instability without committing to austerity policies. Ever since the Asian financial crisis a decade ago, when the Fund was castigated for imposing painful reforms and budget cuts in return for bailouts, IMF officials have tried to develop crisis prevention programs but no country has wanted the stigma of going to the Fund. Several nations, however, have embraced the FCL, seeing it as a seal of approval rather than a diktat with tough conditions. In April, Mexico signed a $47 billion FCL; in May, Poland and Colombia arranged lines of $20.6 billion and $10.5 billion, respectively.

The new early-warning role could give the Fund even greater influence. The initiative will build on the IMF’s long-standing practice of carrying out regular reviews of member countries’ economic policies and institutions. Officials have traditionally focused most of their attention on developing countries, but since the credit crisis erupted, they have spent more time investigating advanced economies. Under the new program the Fund will focus as much on trade and financial linkages between countries as on individual economies and will incorporate the insights of regulators at the FSB. Fund officials will deliver the first of what are expected to be annual early-warning reports to Finance ministers and central bank governors at the IMF’s annual meeting in October.

A key early test of the Fund’s new watchdog role will come next year when it performs its first-ever evaluation of the U.S. financial system. The IMF has been carrying out Financial Sector Assessment Programs in all countries except the U.S. since the Asian crisis. Last year former Treasury secretary Henry Paulson Jr. agreed to submit the U.S. to an FSAP as a confidence-building measure. The Fund has vowed not to mince words. “We will provide a candid assessment,” says José Viñals, head of the IMF’s monetary and capital markets department.

The early-warning role is not without risks. The IMF chaired consultations on trade imbalances and exchange rates among the U.S., the European Union, Japan, China and Saudi Arabia, which concluded two years ago with no concrete results because the Fund didn’t have the authority to force big, powerful countries to alter their policies.

Strauss-Kahn is well aware of the risks but is determined that the IMF won’t pull any punches. “The problem is not, Do we dare?” he says. “Of course we do. The problem is, Do they listen?”

See related article, "Can Finance Be Fixed?"