The war between Georgia and Russia was, inevitably, a brief and one-sided affair. Russian troops, backed by an aerial bombardment campaign, poured across the border into the disputed territory of South Ossetia last month, responding to what Moscow claimed was an incursion by Georgian forces. The Russians routed the army of its tiny neighbor, population 4.6 million, and then pushed into Georgia proper before the two sides agreed on a ceasefire. The fighting, which evoked memories of the Soviet invasions of Hungary and Czechoslovakia during the cold war, unsettled world markets and raised fears of an era of renewed tensions between Moscow and the West.

Georgia responded the only way it could. President Mikheil Saakashvili took to the airwaves and appealed to the world community for help while his prime minister, Vladimer (Lado) Gurgenidze, sought to marshal financial support. Gurgenidze spent the first day of the Russian offensive working the telephones to call investors and rating agencies in a bid to shore up Georgia’s debut $500 million sovereign Eurobond, whose issue he oversaw in April. The bond sank as low as 82 cents on the dollar, but rebounded to 90 cents within a week. As Russian forces rumbled south, cutting the road and blowing up the rail lines between Tbilisi and the Black Sea, Gurgenidze lobbied for a postwar aid package with donors ranging from the U.S. Department of the Treasury to the Asian Development Bank, which Georgia had just joined last year. And as the conflict moved swiftly to its conclusion, the prime minister’s office issued daily bulletins showing that the wartime Georgian lari had appreciated by 0.2 percent against the dollar and that tax revenues were flowing normally — all in an effort to assure the world that Georgia’s economy, which expanded at a blistering 12.7 percent pace in 2007, could quickly resume its growth trajectory.

“Now more than ever we need a set of coherent, radically liberal and extremely investor- and business-friendly policies,” the 37-year-old prime minister tells Institutional Investor.

Gurgenidze’s frenetic activity paid off. He made sure the West’s moral support of Georgia was backed up by hard cash to repair war damage estimated at up to $1 billion, or 10 percent of the country’s GDP. By late last month the World Bank had committed $300 million to $350 million for reconstruction, the International Monetary Fund had dispatched an emergency team to Tbilisi to map out its own assistance program, and the Bush administration had pledged itself ready to “stand behind Georgia so that economic and financial stability can continue,” Assistant Treasury Secretary for International Affairs Clay Lowery tells II. Although rating agencies downgraded Georgia’s sovereign bond rating by one notch — with Standard & Poor’s lowering its rating to B and Fitch, to B-plus — Lowery lauded Gurgenidze’s efforts to inform investors and calm markets. “They kept their investor base up to speed continuously with what was going on inside the country,” Lowery says. “I don’t think a lot of countries would have thought of that.”

The Georgian economy continued to function relatively smoothly, considering the chaos that reigned just an hour’s drive from the capital. Drivers careened about Tbilisi’s streets with their usual perilous intensity, shops were full, and banks reported no runs on deposits. An estimated 130,000 refugees from the conflict were housed without fuss in vacant schools and other public buildings. “It’s surreal here now,” Giorgi Lomsadze, a journalist who reports on Georgian events for George Soros’s Open Society Institute, observed late last month. “On one side of the street, people are hanging out at the usual cafés. On the other side there’s a refugee camp, and you realize there is a war going on.”

Georgia’s defeat by Moscow, and the uneasy peace that followed, put a big cloud over what had been one of the world’s most dynamic economies, with foreign direct investment reaching 17 percent of GDP last year. It also raises new questions about the judgment and durability of Saakashvili, a brilliant but volatile leader whose decision to send Georgian forces into South Ossetia provided an easy pretext for Russia’s assault. If Georgia is to recover quickly from the conflict, it will need some cool-headed pragmatism to accompany Saakashvili’s fervent nationalism. That means the country is likely to rely more than ever on Gurgenidze, whom the president recruited from outside politics last November to help quell domestic political unrest and breathe new life into economic reform efforts.

Gurgenidze has a unique biography among post-Soviet leaders. His last job was as chief executive of the Bank of Georgia, the country’s dominant, long-privatized financial institution. Before that he earned an MBA from Emory University in Atlanta and spent seven years as an investment banker in London. He draws political inspiration from an unusual source, former U.S. senator Barry Goldwater, one of whose 1964 presidential campaign posters is framed on the wall of his modest Tbilisi office.

Goldwater’s laissez-faire, small-government philosophy helped pave the way for Ronald Reagan’s and Margaret Thatcher’s triumphs in the 1980s. “This reflects my political views,” Gurgenidze said several weeks before the Russian conflict. “What we are trying to do here has been described as compassionate libertarianism.”

Gurgenidze pushed through 20 new economic laws this spring that outlawed budget deficits, mandated a single-digit inflation target, eliminated taxes on dividends and made possible a raft of privatizations. The measures are designed to transform Georgia into “some sort of blend of Singapore, Bahrain and Estonia,” as he puts it, a trade and financial hub for the Black Sea region and Central Asia.

Gurgenidze’s ambitions will come to naught without basic political stability, however. Although politicians across the spectrum rallied around the flag during the recent conflict, many observers believe that Saakashvili’s rashness in provoking Moscow could allow opposition to mount in the weeks and months ahead.

It is less than a year since Saakashvili resorted to martial law and mass beatings to quell street protests. Such peremptory behavior, and opaque governmental bookkeeping earlier in his presidency, have tarnished the democratic image that propelled his overthrow of predecessor Eduard Shevardnadze in late 2003. “We believe that the rule of law and democracy are the best way to achieve any goals, but people in the government see this quite differently,” says David Usupashvili, a Saakashvili ally five years ago who now heads the opposition Republican Party.

Gurgenidze promises his government will rebound quickly from the Russian conflict and carry on with free-market reforms to stimulate investment and growth.

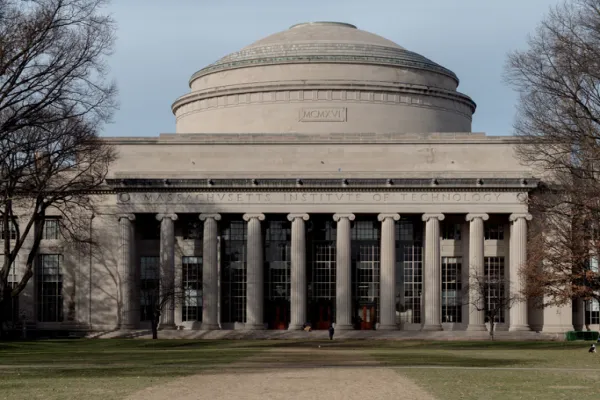

The prime minister is just the most senior of an under-40 brain trust with U.S. degrees and multinational résumés that Saakashvili has hired since sweeping to power on the back of the Rose Revolution, so named for the flowers many demonstrators handed to riot police. Finance Minister Nika Gilauri, 33, has a master’s degree in management from Temple University in Philadelphia and was a consultant to Spanish utility Iberdrola. David Amaglobeli, the 32-year-old acting president of the National Bank of Georgia, did graduate work in economics at Oregon State University. Minister of Economic Development Ekaterina Sharashidze, 34, boasts graduate degrees from both Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was formerly employed by Goldman, Sachs & Co. Saakashvili himself, who is 40, attended Columbia Law School and worked briefly as a corporate lawyer in New York.

This hyper-Westernized clique launched one of Eastern Europe’s boldest experiments in modernization by shock therapy, with impressive results. The revolutionaries fired 40,000 public employees, clearing out entire ministries and most of Georgia’s police force. They dropped the number of different types of taxes collected in Georgia from 22 to seven, and slashed the corporate tax rate from 47 percent to 20 percent. Higher compliance with the lighter regime led to a fivefold increase in budget receipts, and pensions rose to $50 a month from a derisory $7. “We have proven that supply-side economics really works,” Gurgenidze boasts.

Saakashvili’s team also slashed red tape and bureaucracy. It now takes 45 days to open a bank in Tbilisi, says Nicholas Enukidze, a childhood friend of Gurgenidze’s who is chairman at Bank of Georgia. By contrast, it takes six months in Ukraine, where BoG bought the midsize Universal Bank of Development and Partnership for $81 million last year. Georgia ranked 79th out of 179 countries in the latest corruption perceptions index published by Berlin-based watchdog Transparency International. Ukraine finished 118th and Russia, 143rd. “We can definitely say that the government has defeated visible, daily corruption,” attests Badri Japaridze, deputy chairman of Bank of Georgia’s top rival, TBC Bank.

Saakashvili’s administration has also restored basic services that Shevardnadze left in shambles. Trash is collected; heat and power are reliable. “I remember having a heart attack in 2000, and no one could move me downstairs until the elevator started working in the morning,” says Alexander Rondeli, president of the Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies, an independent think tank in Tbilisi. “This year, even when the Russian Army was 25 kilometers from Tbilisi, all municipal services still worked.”

The Georgian economy responded to better governance with a bracing expansion, last year’s spurt following 9.4 percent growth in 2006. Tbilisi, an ancient capital nestled in the Caucasus Mountains, with vaulted stone churches dotting its high ground, still has a dilapidated feel away from its central boulevards. Paved streets run off randomly into gravel and dirt, and stray dogs wander at will. Beyond the capital, half of Georgia’s population still lives on the land, eking out 11 percent of GDP on tiny plots worked with manual implements.

But signs of budding enterprise are everywhere in Tbilisi. The tumbledown Mediterranean-style houses are increasingly likely to have a Mercedes or BMW parked out front. Tiny shops with a just-opened feel cram the bigger streets: bakeries, locksmiths, furniture repair, maternity clothes, Internet cafés. Banking credit has expanded by 60 to 65 percent annually for the past four years, central banker Amaglobeli reports, spurred by both small business and the birth of retail lending.

Georgians were known for their subterranean entrepreneurship in Soviet times. Now they are registering 5,000 new businesses a month, says Kakha Bendukidze, the deputy prime minister who left a successful business career in Russia to become Saakashvili’s first economics czar. “Georgian culture is family-based and very egocentric. Every person thinks he’s a king,” he observes. “That makes a very good environment for small business, though not an easy one for big organizations.”

The country’s leap forward has won Saakashvili’s team respect tempered with some personal reservations among the, until recently, narrow circle of Westerners watching Georgia. “Misha and the people around him are arrogant,” says a European diplomat in Tbilisi, referring to Saakashvili by the widely used diminutive of his first name. “They think they are God’s gift. But I wonder if anybody else could have pushed through all these reforms.”

Yet from the outset Saakashvili’s blend of self-assurance and zeal has bred habits more authoritarian than libertarian. He kicked off his presidency in 2004 by arresting scores of officials and businessmen linked to Shevardnadze until they coughed up cash via so-called plea bargain agreements. He then channeled tens of millions of dollars from these oligarchs’ fines to opaque “special funds” controlled personally by the Defense and Interior ministers. The funds were eventually closed after hectoring from the IMF and Western embassies. By November 2007, Saakashvili had made enough enemies to nearly undo him. Tens of thousands of demonstrators filled Parliament Square in Tbilisi for five days with demands ranging from early elections to increased pensions. The president decried them as agents of Russia, then finally declared a state of emergency and sent the police to disperse them using tear gas and rubber bullets. Hundreds of protesters were injured in the ensuing melee, and the TV station that had egged them on was shut down.

But Saakashvili also heeded the demand for elections, calling a snap presidential poll in January and a vote for Parliament in April, and he jettisoned incumbent premier Zurab Noghaideli in favor of Gurgenidze.

Before Gurgenidze took office last November 22, his public life had been limited to hosting the local version of The Apprentice on Georgian TV. He had left his native Tbilisi in the early 1990s for Middlebury College in Vermont, and Emory, then spent half a dozen years with ABN Amro in London and Moscow, rising to global head of investment banking for the technology sector before coming home to run Bank of Georgia in 2004. In three years he doubled the bank’s market share, to 35 percent, and listed its shares in London, increasing its capitalization 38-fold. Foreign institutions now own 87 percent of BofG, led by New York–based Firebird Management, with 10.7 percent. ( It was Enukidze, who had become chairman of BofG, who persuaded Gurgenidze to come home and run it in 2004.) “This is a job, not a career,” Gurgenidze says of being Georgia’s second-highest official. “I’ll probably end up running money somewhere.”

Yet the libertarian banker helped give the Rose Revolution a second wind, with considerable assistance from a divided opposition, which for its presidential candidate chose Levan Gachechiladze, an error-prone winery owner with next to no economic program. The government’s United National Movement party went on to triumph in the parliamentary balloting, gaining 120 of 150 seats.

“Gurgenidze practically saved the government by playing the role of the new man,” says Kakha Gogolashvili, director of European studies at the GFSIS. But that was before the war.

The Prime Minister’s 20 new laws, all passed between March and May, enshrined fiscal probity into Georgian statute. The central bank actually hiked its discount rate from 7 to 12 percent this spring in a campaign to keep price rises in single digits. “Very few countries had the [nerve] to increase rates by 5 percent in the face of the credit crunch,” Gurgenidze notes approvingly. The aggressive policy wrestled inflation down to 9.8 percent year-over-year as of August, compared with about 15 percent in Russia and 30 percent in Ukraine.

Gurgenidze pushed through enabling legislation for a new round of privatizations, including, most controversially, the entire state health care system. In its place the government would subsidize insurance payments according to need, he says. The premier also tried to lay the legal foundations for his personal dream of turning Georgia into a major offshore financial center.

To this end Georgia’s dividends tax is being scaled down to zero from its current 10 percent, and foreign-registered financial companies will pay no taxes at all so long as they do not have Georgian clients. But a financial haven must first of all be a haven. And even if Russian troops complete their withdrawal to South Ossetia and Georgia’s other breakaway province, Abkhazia, and stay there, Georgia’s economic ambitions have sustained a severe blow that was partially self-inflicted.

Gurgenidze, not surprisingly, stoutly defends Georgia’s wartime conduct and predicts a quick resurgence of tigerish economic performance. “Georgia just returned fire after heavy shelling of civilians by the separatists and after reports that a large column of Russian troops was entering Georgian soil,” he told II in a telephone interview late last month.

Observers beyond Georgia are less kind, calling Saakashvili rash for stoking hostilities even as they condemn Russia for invading Georgia. “It was utterly irresponsible of Saakashvili to attempt a military solution rather than build Georgia’s economy and make it a nice place to live,” says Jack Matlock, U.S. ambassador to Moscow from 1987 to 1991 and now a professor at Columbia University’s Harriman Institute for Russian, Eurasian and Eastern European Studies. Gurgenidze consoles himself with the thought that the August events transformed Georgia from a footnote to post-Soviet history into a global front-page item, portrayed sympathetically as a plucky bootstrap democracy bullied by a revanchist Kremlin. “The one possibly constructive outcome of this tragedy is that the world community has become far more focused on resolving Georgia’s problems,” he says.

A generation ago Cyprus was also riven by ethnic violence between Greeks and Turks, and until last year a Berlin-style wall still divided its capital of Nicosia, ignored by the legions of bankers and attorneys calmly tending to their clients’ offshore fortunes. Benign neglect of intractable ancient conflicts is, for many countries, an essential part of moving pragmatically toward a prosperous future. Georgia still has a shot at becoming one of those countries, thanks to all the forward momentum built up since 2004. But it has to hope that President Saakashvili has learned the Cypriot lesson, and not learned it too late.

Front Line Capitalist

Since he was appointed prime minister by President Mikheil Saakashvili last November, Vladimer (Lado) Gurgenidze has reinvigorated an economic reform program that aims to make Georgia a bastion of capitalism in the Caucasus. The U.S.-educated Gurgenidze, a former investment banker, pushed through Parliament a package of measures outlawing deficit spending, cutting taxes and paving the way for large-scale privatizations. The sudden conflict with Russia, which invaded the disputed Georgian provinces of South Ossetia and Abkhazia last month and then recognized them as independent states, cast a dark cloud over Gurgenidze’s ambition, as well as over the future of Saakashvili’s presidency. But the Prime Minister reaffirmed his vision in a telephone interview, saying, “now more than ever we need a set of coherent, radically liberal and extremely investor- and business-friendly policies.” Earlier this summer, before the conflict, the prime minister laid out his economic vision in an interview with Institutional Investor Contributing Editor Craig Mellow at his office in Tbilisi.

Institutional Investor: What does Georgia want to be in 20 years? President Saakashvili has mentioned the next Singapore or Dubai. What’s your view?

Gurgenidze: Georgia is undeniably part of Europe — culturally, politically, historically — so we aspire to be a meaningful member of the bigger European family. In terms of our economy, I would say we want to be some sort of blend of Singapore, Bahrain and Estonia. That means as much economic liberty as possible and playing a disproportionately large role in the regional financial and trade flows.

We aspire to be a financial center. If you look at the map, there is nothing of the sort, or not much, between Dubai and Cyprus. We can trade on the ease of doing business here and on our low, transparent tax regime to become a regional center for fund administrators and trust services.

What needs to happen now?

Back in March, despite the election season and everything else, we pushed through a package of 20 new laws and significant changes to existing laws. That was a very major first step toward turning Georgia into the sort of jurisdiction I just described.

We have written into the budget law that it is illegal to have a deficit. On the monetary side, we have made it illegal for the central bank to have an inflation target in the double digits, and we have a clause that calls for a vote of no confidence in the central bank governor if the bank overshoots the inflation target by more than 2 percentage points for four consecutive quarters. I’m not aware of any other laws worldwide that are as hawkish.

Taxes were already very low and flat here, but as good libertarians, which many of us are, we will now reduce the personal income tax over the next five years from 25 percent to 15. There is no separate social tax or anything else. We will also reduce the dividend tax to zero from the current 10 percent. Starting January 1 next year, we have abolished all taxation on financial instruments. If you register a foreign financial company here, you can be completely free of any tax, including profit tax.

The tax burden now is the lowest in the country’s history. Yet in the past five years, the budget revenues have grown fivefold.

Is the international economic crisis affecting Georgia?

Very little. The resilience of the Georgian economy has surprised everyone, myself included. We’ve been growing by 10 percent or more for the past several years despite the Russian trade embargo, the commodity price cycle and the credit crunch.

The reason is economic liberty — the government trying to get out of the way of the private sector as fast as it can. We are in the process of privatizing the health care sector, and all the hospitals will be privatized. That is how far we have gone with this.

Will that be accompanied by an insurance program?

We have a program, but even that is market-based. We just give the people below the poverty line a voucher that they are free to take to any of the insurance companies.

For all the progress, dynamism and liberties achieved since 2004, we still have about a million people [from a population of 4.6 million] below the poverty level. And that million must know that reform is not a dirty word, that they have not been forgotten. That’s why we have increased the pensions and we are underwriting this very large-scale health insurance program. We have cut back on infrastructure spending so we don’t increase government spending as a percentage of GDP.

What are you going to do for the rest of your life?

That’s a very good question. I’ll probably end up running money somewhere somehow. This is a job, it’s not a career.