The corridors of Guggenheim Advisors’ New York offices are lined with photos of architectural gems: distinctive art museums in Berlin, Bilbao, Las Vegas, New York and Venice that bear the fabled family name.

Guggenheim Advisors has created no less distinctive an architecture for its funds of hedge funds. Founded in 2002 by the Guggenheim family office as Guggenheim Alternative Asset Management, the firm invests about $3 billion in hedge funds for its four dozen clients, which include wealthy families and institutions. But unlike conventional fund-of-funds firms, which allow clients’ money to disappear into often-opaque portfolios of hedge funds, Guggenheim sets up separate accounts with each manager it uses.

“We don’t invest our clients’ money in hedge funds but rather with hedge funds,” says Guggenheim chairman and CEO Loren Katzovitz. “We know exactly where our money is.” The firm then monitors a slew of data to ensure that the funds stay on track, much as if Guggenheim were making the investments itself. Katzovitz, 44, who co-headed Royal Bank of Canada’s equity derivatives and proprietary trading division in New York before joining Guggenheim in 2002, describes his firm’s model as analogous to “outsourcing the traders” at a Wall Street investment bank’s prop trading desk.

Guggenheim also tailors its portfolios to clients’ risk-and-return parameters, choosing among 35 to 40 hedge funds. “It’s not just a single pot of money,” says the firm’s president, Patrick Hughes, 45, who worked for Katzovitz at RBC and moved with him to Guggenheim. “It’s not every client getting the same solution.” Some want Guggenheim to create a portfolio to meet their return and volatility targets, and others want a voice in choosing the funds.

For such services clients pay Guggenheim management and performance fees on top of those charged by the underlying fund managers. Katzovitz says the firm’s fees are in line with those of other funds of hedge funds. Guggenheim won’t discuss performance, saying that its growth speaks for itself. Hughes adds that because the firm customizes client accounts, results vary.

Conventional wisdom holds that the allure of funds of hedge funds will wane as investors grow wiser about hedge funds and balk at the extra layer of fees and the one-size-fits-all strategy. To survive, Katzovitz says, funds of hedge funds will have to copy Guggenheim’s formula.

Dennis Sugino, president of consulting firm Cliffwater in Marina del Rey, California, sees a pattern of “managers coming out with more-specialized types of funds of hedge funds — they’re bundling fund investments together into a more risk-controlled model.” And risk control is Guggenheim’s sine qua non. Alan Dorsey, managing director of nontraditional research at CRA RogersCasey, a Darien, Connecticut, consulting firm, concurs: “Funds of hedge funds are developing a much broader set of products to defend their territory against multistrategy funds.”

Guggenheim Advisors’ singular approach and rapid growth — from $500 million in assets in 2002 to $3 billion today — has attracted one very interested party: Bank of Ireland. In January the Dublin-based bank paid $184 million to acquire 71.5 percent of then–Guggenheim Alternative Asset Management from Guggenheim Partners, the $100 billion-in-assets onetime family office of the Guggenheims. Chicago-based Guggenheim Partners, which manages money for rich families and institutions, retains a 17.5 percent interest in Guggenheim Advisors; the remainder is split among the funds-of-funds firm’s senior managers.

Kevin Dolan, CEO of Bank of Ireland’s asset management division, gives a bleak assessment of traditional funds of hedge funds. “If a fund of funds is just investing in single hedge funds and hoping for good returns and providing monthly reports, that business model is pretty much dead,” says Dolan, who spearheaded the acquisition (see box). “On the other hand, a platform like Guggenheim’s really adds a lot of value in terms of risk monitoring and reporting and controlling the assets.”

Katzovitz and Hughes designed their business to replicate a proprietary trading desk. “If you go to a firm like Morgan Stanley and look at its prop trading desk, you’re going to see two things,” says Katzovitz. “You’re going to see the traders, who have been given guidelines and mandates by management, and you’re going to see another room that has the risk department, which oversees every single thing these traders do. What we’ve created is basically that: We have a risk team that oversees everything our ‘traders’ are doing.” Guggenheim’s traders, however, are hedge funds.

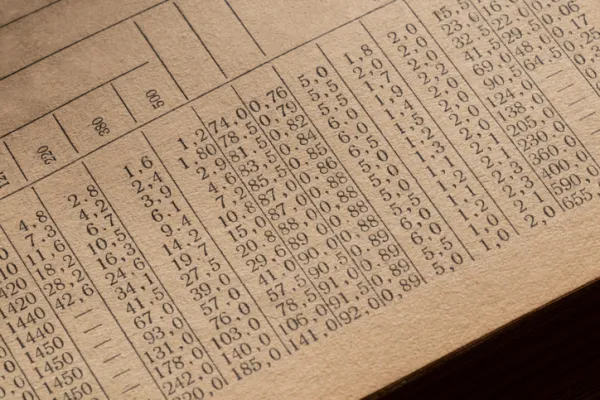

Every night the firm receives all of its 6,000 or so positions from its hedge fund managers and, by blending them, gets a fix on where the firm stands. “With our separate accounts,” says Katzovitz, “we can have a real-time P&L.” The data, printed out in multicolored charts, enables Guggenheim to make nips and tucks to control its risk.

The firm gauges such variables as portfolio liquidity, neutrality and turnover. “We have over 200 various stress tests that we look at,” boasts Hughes. These show what might happen to a portfolio if, say, the market drops while volatility doubles. Hughes says the firm can coordinate its analyses with a client’s total exposure: “If an institution has other funds, such as long-only accounts or separate accounts, we can integrate them and give the client one customized risk report.”

Guggenheim’s 38 professionals can spot excessive concentration and smooth out exposures, much as an orchestra conductor brings up the strings or tones down the brass. Suppose several of the firm’s managers build positions in consumer retail stocks. “We would want to bring down our exposure,” says Hughes. “It could be done by taking away some money, but because we’re growing, it’s a question of allocating or not allocating new money to certain managers.” At its most basic, the rigorous portfolio review minimizes the prospect of Guggenheim’s being conned by a rogue hedge fund.

What do hedge funds think of all that scrutiny? Cliffwater’s Sugino wonders “why any hedge fund manager would give them the level of transparency they’re getting.” Some hedge funds do grouse at having to run a separate account for Guggenheim, Katzovitz admits. But, he adds, “being able to give somebody $50 million to $75 million, as opposed to $20 million, helps.” Contends Hughes, “We really hit very little resistance.” Guggenheim signs strict confidentiality agreements.

The firm’s officials grant there’s nothing special about how they pick funds. “We’re basically trying to find someone with a good pedigree as a trader,” says Hughes. “We don’t necessarily look at how long they’ve been a hedge fund or what their assets under management are. We look at whether they have a repeatable process.”

A couple of Guggenheim’s current funds are New York–based Scoggin Capital Management, an event-driven and opportunistic fund with $500 million under management, and Scout Capital Management, a $3 billion long-short value-oriented fund.

Guggenheim always knows what its managers are up to. “To the extent that they’re doing something other than what we asked them to do with the money, we can see that,” says Hughes. When the firm detects managers deviating from their investment scripts, Hughes or another team member gives them a call. “It’s not necessarily to harass the manager,” Katzovitz says. “It’s to educate us.”

Jeffrey Berkowitz vouches for that. He runs some Guggenheim money in J.L. Berkowitz & Co., the New York hedge fund firm that was Cramer Berkowitz until James Cramer left at the end of 2000 to pursue his media career. “They’re unobtrusive,” says Berkowitz. “They never call me up and say, ‘Why are you doing this?’ or ‘What’s wrong — why is your performance suffering?’ A few times we struggled a little bit, and they were really supportive.”

Guggenheim’s information highway is a two-way street. “Their analytics are great,” says Berkowitz. “They can take things to a third or fourth level and utilize their risk management tools. I check in with them every few weeks and use them as a sounding board.”

Investors in the firm find Guggenheim’s information bank helpful for the same reason. “Loren Katzovitz has a great risk-reward understanding of the marketplace,” says one Guggenheim investor, Don Torey, an executive vice president of GE Asset Management and CIO of its alternative investments. “He knows the landscape as well as anybody, so we use him for insights.” Guggenheim has helped GE assess the portfolio impact of market drops.

As obsessed as Guggenheim is with details, it keeps focused on the big picture, in part through an advisory board that includes Lawrence Lindsey, a former assistant to the president for economic policy and ex-director of the National Economic Council. Other members include former ambassadors Stephen Bosworth and Ed Gabriel, former U.S. senator Fred Thompson and two former energy executives. Lindsey says the board’s mission is to forecast the unexpected. Although the board “can’t predict if a meteor will hit the earth,” says the economist, who runs his own Washington consulting firm, it can outline what to expect on global trends. The group meets three times a year to brief Guggenheim.

Information of all sorts is prized at the firm. Hughes scoffs at traditional hedge funds’ reticence: “You get 12 statements a year, and then comes January — you pay a bonus, and in April you get an audit that says what you did last year.” That’s not how a prop desk — or, by inference, Guggenheim — does it, he says. “Morgan Stanley does not hire a trader and say, ‘I’ll pay you in advance; I’ll see you at the end of the year; you mark your own books; here’s my capital.’”

Katzovitz and Hughes invoke the prop desk mantra so often it gets boring. “To some degree, it’s marketing,” allows Ted Gooden, a partner at Berkshire Capital, a New York–based investment bank that specializes in the asset management industry. But he also says their approach is “highly respected” and “pretty original.” Cliffwater’s Sugino agrees that Guggenheim has an unusual strategy. The consultant, however, points out: “You could be coinvesting, but it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to do well. You’ve got to coinvest with successful managers.”

Katzovitz warns those who would imitate the Guggenheim approach, “There’s a whole lot of cost.” For a start, the firm has some 30 analysts crunching numbers all day. Guggenheim was able to pull it off, he says, because it was lucky enough to have a half dozen investors willing to let the firm spend on processes to create risk reports and monitor portfolios “the way you would if you had a prop desk and it was your money that was being invested,” says Katzovitz, altogether predictably.