Breaking news: Endowment investors weren’t actually imbeciles before David Swensen came along.

Conventional wisdom on the outskirts of finance often assumes that before the rightfully legendary Swensen took over the Yale Investments Office in 1985, university capital pools the world over were thoughtless bond buckets. Only after Swensen took the reins did nonprofit capital surge into both modern investment management and industry prestige, the thinking goes.

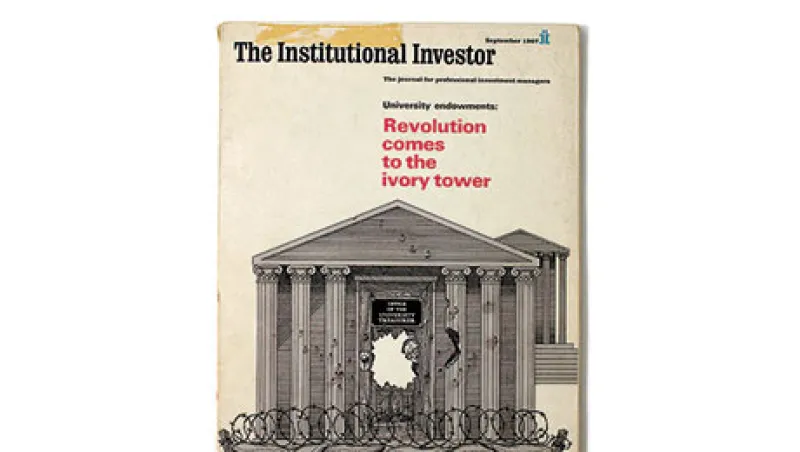

Readers of the September 1967 edition of The Institutional Investor knew otherwise. “University endowments: Revolution comes to the ivory tower,” the cover proclaimed. Inside was a prominent profile of Harvard’s Paul Cabot — the “distinguished ex-treasurer” and the “dean emeritus” of “university money managers” — explaining how the endowment had gone from $200 million to $1 billion under his tenure. “Harvard was among the most aggressive of university investors in the late ’40s and early ’50s,” the article explained. Prior to running the coffers at Harvard, Cabot had founded and led State Street Research & Management Company. He applied that investment expertise at the endowment, expanding its equity allocation across 175 different stocks, at the time of II’s publication.

Harvard would eventually follow Swensen’s lead into alternatives — and, for many years, reap the benefits. But it’s also clear that endowment investing was an innovation incubator long before Yale’s dean of nonprofit investing stepped on the scene.

The September 1967 issue also contained a cautionary tale. Directly following the profile of Harvard’s Cabot was another: “How the University of Rochester Built Its Endowment.” That pool of capital, II reported, had grown from $81 million to $346 million over the previous 15 years. It had done so by moving to an equity allocation of 65 percent, while holding only 27 stocks. At the time, the University of Rochester’s was the fifth-largest endowment in the U.S.

But nearly 75 percent of its common stock holdings were in just two companies: Eastman Kodak and Xerox, the local giants of the time. The holdings were also at least somewhat by choice: “Although much of its Kodak stock was a gift from the George Eastman estate, all the Xerox it now owns ... it bought in an account labeled ‘Funny Money,’” II wrote. “Any other endowment fund could have done the same, at exactly the same time and at the same cost.”

Fifty years on, they’re lucky they didn’t. Kodak and Xerox have both deteriorated, and the university’s endowment has along with them. According to the National Association of College and University Business Officers, as of 2015 the fund amounted to a relatively paltry $1.93 billion, a growth rate of just 3.5 percent per year (including any gifts added to the endowment) over 50 years. It is now the 44th-largest endowment in the country.

By comparison, the Yale endowment grew from $446 million to $25.5 billion over the same time frame, an annualized growth rate of 8.4 percent.

Perhaps David Swensen was a revolutionist after all.