To view a PDF of the report, click here.

Poland leads the way

December to become Europe’s first sovereign issuer of green bonds, the news was greeted by the cognoscenti of the sustainability finance market with a mixture of surprise and delight.

There was initial astonishment at the announcement from Warsaw because Poland is hardly known for its evangelism in the fight against greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), which has called on the government to clean up its energy sector, 81 percent of Poland’s power came from coal in 2015, and just 14 percent from renewables. “Poland’s annual mean concentration values of BaP [benzo(a)pyrene], found in coal tars among other things, and a cause of lung cancer, are the highest in Europe,” is one of a number of disturbing indicators mentioned in the IEA’s 2016 review of Poland’s energy policy.

This made Poland’s emphatic public statement about its commitment to cleaning up its environment all the more welcome. “We don’t hide the fact that we make intensive use of coal, which is our cheapest form of energy,” says Piotr Nowak, Undersecretary of State at the Ministry of Finance in Warsaw. “But we also want to make it clear that we see ourselves as part of a community that cares strongly about the environment and sustainable development, and to demonstrate that we have a number of ongoing green projects.”

Poland’s Green Bond Framework

Specifically, the proceeds from the Polish bond were earmarked for six areas detailed in the Green Bond Framework published by the government last year. These are renewable energy generation, clean transportation, sustainable agricultural operations, afforestation, national parks, and the remediation of contaminated land.

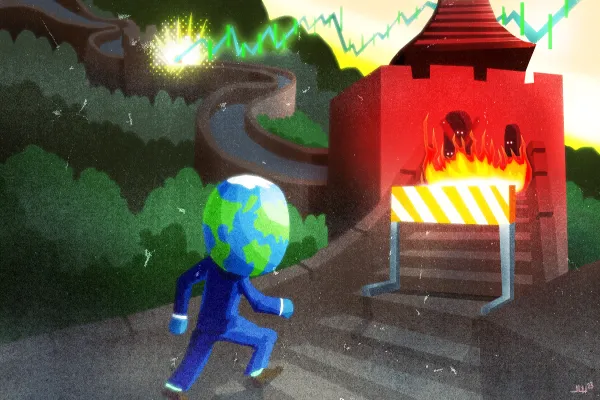

Some regarded the Polish initiative with caution. The London-based Climate Bonds Initiative welcomed the deal, but warned that the beneficial impact of these projects would be “completely negated” if investment in fossil fuels continues.

Nevertheless, champions of the green bond market were delighted by the launch of Poland’s €750 million five-year transaction — for at least two reasons. The first was that the issue, led by HSBC, JPMorgan and PKO Bank Polski, opened up an important new source of supply for the market. Although sub-sovereign and municipal borrowers from Johannesburg in South Africa to Gothenburg in Sweden have issued green bonds in the past, this was the first deal of its kind from a pure sovereign. According to Nowak, this created an unexpected complication in the marketing of the transaction. “Up to now, dedicated green accounts have typically been corporate bond funds, without a mandate to buy sovereign paper,” he explains. “So a number of investors had to get special approval from their risk departments to buy our bond.”

Appetite for the Polish issue and the pricing of the bond demonstrated the strength of investor demand for exposure to green issuance. Robust pre-issue demand allowed for the size of the deal to be increased from its originally indicated €500 million. It also allowed pricing to be set at 48bps over mid-swaps, flat to the Polish Government’s yield curve.

Strong demand also helped Poland to achieve one of its key objectives, which was to continue to diversify its investor base. “One of the reasons we were so pleased with how well the transaction was received was because 61 percent of the bonds were bought by dedicated green investors, almost all of which were new to the Polish sovereign credit,” says Nowak.

Now that Poland has established a green benchmark, Nowak says that the Treasury intends to build on its success. “We have indicated that this won’t be a one-off,” he says. “Our aim is to issue green bonds with some degree of regularity.”

This commitment will be welcomed by investors because it touches on the second — and perhaps more important — reason why stakeholders across the green bond universe were so delighted by December’s curtain-raiser for sovereign bonds in green format. This was the conviction that if coal-intensive Poland could embrace sustainable finance, then so could scores of other governments.

Nowak says that if the interest in Poland’s bond is any guide, there is no shortage of other sovereign borrowers that are studying the potential of the green market. “A number of sovereigns have asked us to share information with them about the documentation of the use of proceeds,” he says. “The main challenge for a sovereign issuer is to verify that the proceeds are not used for general purposes. So we opened a separate account which allows investors to follow the use of proceeds very closely, and ensure they are being used for green purposes.”

Growing interest from a number of sovereign borrowers in developed and emerging markets alike supports the upbeat forecasts made by some analysts about the potential continued expansion of the market in 2017. Moody’s, for example, advised in January that issuance volumes would set another record this year. The agency’s projection that new supply in 2017 may reach as high as $206 billion, compared with $93.4 billion in 2016, was based largely on continued robust growth from China and momentum generated by the Paris agreement on climate change in late 2015. — Phil Moore